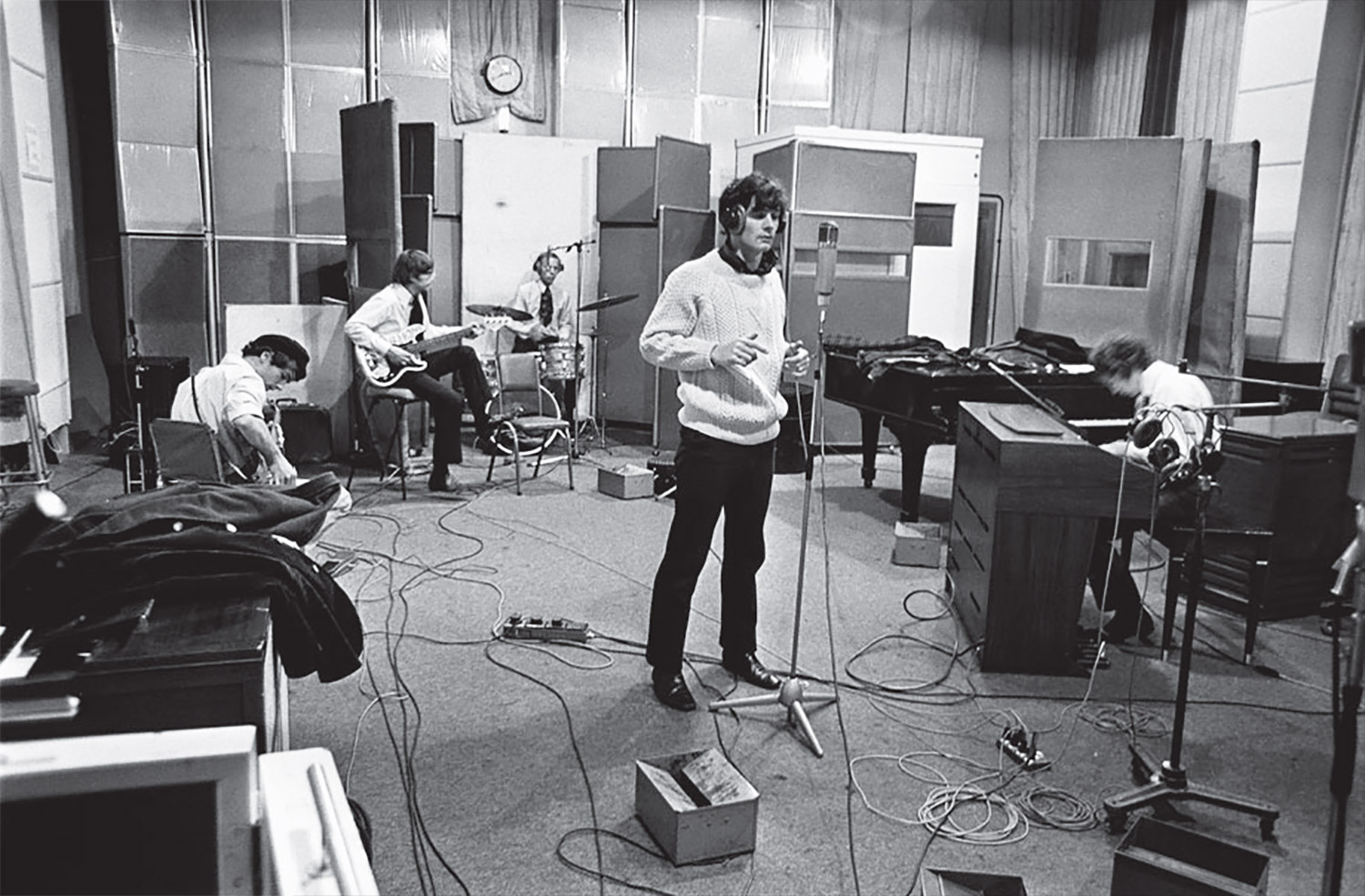

I heard your first studio session, in 1964, involved a drunk engineer who'd been at a wedding?

It really did, yeah! A very fine engineer actually; we just got him on the wrong day. It was Terry Johnson. I was reading something about Glyn Johns [Tape Op #109], and he mentioned working with Terry Johnson. We loved what he did on the recording, it's just that he was completely abusive; he was shouting and screaming at us! I know that Colin said, "If this is what being a professional musician is, I don't want to know! This is going to be a very short career for me." The piece of luck was that Terry passed out completely, and the four of us carried him upstairs into a London taxi and sent him home. The taxi driver saw to him somehow. He came back the next day and mixed "She's Not There." Gus Dudgeon did take over for the main part of the session. That was genuinely Gus's first foray into being the prime engineer in a session!

Obviously his career went on to be spectacular.

It was. I know.

That was at Decca's West Hampstead studios?

That was the one, yeah.

Was your first album, Begin Here, really done in a two-day session?

The first four tracks that we ever recorded were done in a one-day session. We started into the afternoon and went on until about three o'clock in the morning, as I remember. We recorded "It's Alright With Me," which was the first song I remember writing, "She's Not There," which was the second song that I'd written, "You Make Me Feel Good," which was a Chris White song that turned out to be the B-side, and [George Gershwin's] "Summertime." We recorded those four tracks completely in that one session. The next day we weren't even allowed there. We had a very autocratic record producer who didn't want us around when he mixed, but that's how things were done then. I remember Russ Ballard – from my second band, Argent – knew The Beatles from when they were semi-pro. He was wandering around the West End in London, and they were walking the other way down the street. They said, "Oh, hello Russ. We just recorded our first album yesterday." They did the whole thing in one or two days. That's how records were done then.

Right. So quick.

But I'll tell you what, we tried to go back to some of that feeling when we did our last album, Still Got That Hunger, in 2015. We wanted to go back to this feeling of capturing a performance and not overlaying and overlaying. We got producer Chris Potter [The Verve and Richard Ashcroft], and we ensconced ourselves in the studio. He was in the control room, and we concentrated on performing together. We got Colin to sing guide vocals, which all turned out to be master vocals. The whole thing worked so beautifully. We didn't even use a click track, which Chris Potter was very worried about. He said, "Look, we've got to use a click track if we want to add things later." We said, "No, we don't want to do that. We just want to do things the way that we used to do it and have that freedom." In fact, our tempos were so good that on a couple of songs we did cut between tracks, but you can't tell the difference because the tempo is identical. The idea was that we were going to record the whole album in five days; the following five days of the next week we were going to concentrate on lead vocals and solos, basically, and then do any overdubs and vocal harmonies. In the end, the whole thing worked so well that we didn't replace any solos. They were all solos that were done as we were recording and capturing that performance. Pretty much all the vocals were done live as well. So the following five days we spent on backing vocals; doing that in a leisurely way, double-tracking the backing vocals, and so on. But for the meat of the track, everything was done live. That was us deliberately trying to recapture some of that energy and spark that you get from trying to work up a performance to the point where you feel, "That's it. We've got a little bit of magic." Then Chris took a day for mixing, but we deliberately left that up to him. I know The Stones have just done their new album [Blue & Lonesome] in three days, doing old blues covers.

Right. I heard about that.

It's really good. It's very rough, but great.

I think one thing that really sets The Zombies apart is the chordal colors and voicings that you come up with.

Thank you. We always try to explore music harmonically, in terms of chord progressions, and in terms of voicings and harmonies too. I don't think there were many bands that didn't just do harmonies in root, third, and fifth; everyone singing in parallel, pretty much. We always looked at it as something a bit more. I think The Beatles intuitively did some very creative things with their harmony voicings. And the Beach Boys, of course; Brian Wilson certainly did this.

You've seen the recording process go from bashing it out really fast, to the '80s where we got into MIDI, and then to Pro Tools and minute control.

I did all that! I produced the first Tanita Tikaram album [Ancient Heart] with my colleague, Peter Van Hooke, which ended up selling four and a half million in Europe. Tanita had only ever played with voice and guitar before. Pete would put a very, very simple drum loop down, and he'd get her – in a very comfortable way – to record the songs with just voice and guitar. And then we completely got rid of the drum loop. Pete and I played just about everything on that first album, apart from a couple of featured people we got in on a couple of tracks. We did that in an incredibly layered way. Sometimes we even changed the chords, if we felt that it would be creative for a song. We gave ourselves room to extend in every way possible, but that was only possible to do by layering the tracks. So I have done all that, and I've done it in a very successful way. But we really wanted to get back, this time, into that freshness of feeling that you get. It also means that we can do anything from the album on stage, without a problem, even more easily than on Odessey and Oracle. On Odessey and Oracle I was typically laying down a piano part, and then a Mellotron part. We will be playing it live a lot this year, because it's the 50th anniversary. This is going to be the final time that we perform it, in many places. We have to have extra people to reproduce all the notes that were on Odessey and Oracle. But with our new album, we don't. It is just the five of us; pretty much live. We can get out there and do the songs, and it really works.

I saw you in Portland doing the Odessey and Oracle show in 2015. I thought, "They must be bringing extra keyboard players!"

We certainly did. We were very lucky to have Darian Sahanaja, from Brian Wilson's band. Darian knows the Mellotron parts better than I do! He's such a fan, and it's so sweet. We trust him totally. I'm very worried about doing it with anybody else, in case of him not being available. We are doing it all over the place this year. We're doing it at European festivals, we're doing it in the UK, as well as in America. Of course Darian's still got his commitments with Brian as well.

Right. When you were recording Odessey and Oracle, had someone just left a Mellotron at Abbey Road?

Yeah, that "someone" was John Lennon. Basically The Beatles walked out a week or two before we walked in, having recorded Sgt. Pepper's... We were the next band in and we worked with the same engineers, Peter Vince and Geoff Emerick [Tape Op #57]. We worked with some of the studio's technical, cutting edge advancements that they'd forced the boffins there to make, and we had the benefit of some of the equipment they'd left around in the studio. One of those things was John Lennon's Mellotron. If it hadn't had been there, I wouldn't have used it. But I loved it, and it became quite a defining sound of the album.

Listening to your work before that, it's very organ or piano-based for your parts. Did you have to focus on how you were going to integrate the Mellotron, as far as arrangements?

Strangely enough, it was all very natural. In my head, I would really rather have had a string orchestra at the time, but we couldn't afford that in any way. So what a great substitute! But, of course, it has totally its own sound. The fact that it's so lo-fi, in a way, turned out to its advantage. Each note plays for 8 seconds or so, and then stops. You can't just play it and sustain forever. You have to develop a technique very quickly where you know when the note is going to run out, and you have to change voicings by that time, because you can't just keep your hand held down on it.

There's no prolonged sustain.

Yeah. In a way, that colors what you're doing too. But it's that old thing of when you have boundaries and limits, it sometimes is a very creative thing. It forces you to work in a different way, and it forces your creativity into a slightly different path. In the end, I'm so grateful that that was there. Having strings on it would have been a much more ordinary thing. Having a Mellotron gave it a real character. We loved it. We didn't have much money when we were recording Odessey and Oracle – we had a thousand pound budget out of CBS, and we had to record the whole album. So even though it was recorded over a period of quite a few months, it wasn't us being in the studio for months. It was a series of three or six hour sessions, and that was it. Typically, a track was done in a day. It was done very much in a live way, but with the benefit of overdubs, which felt wonderful to us. We'd never had the benefit of having seven tracks, I think it was, because one of them had to be bounced down, and one of them had to be used as a sync track with two machines. I think The Beatles were working with that idea with the engineers. It meant that we would do what we'd rehearsed very carefully. We'd put the basic track down. For instance, on "Changes" I said, "Hey Chris," (because that's his song,) "I can hear a top harmony there." That little [hums melody] was just off the top of my head. He said, "Yeah, go in there and do it." Bang. We did it because we had an extra track to do it on. Then we'd say, "Why don't we put a little bit of Mellotron on the track?" Either flute or strings; basically it was just those two things. More often than not it worked beautifully. It was done in a very simple way. There weren't hundreds of overdubs, like you can do now with unlimited tracks. That also helps, I think. You're making your choices as you go. Each choice has to be very telling, because you're talking about extra overdubs, but we're probably only talking about one extra keyboard. Like on "Time of the Season," an extra tom-tom or an extra harmony. Or giving a couple of the guys, myself and Chris maybe, an extra two parts to sing on or, occasionally, double-tracking vocals. So we had the luxury of doing that, but it means that on things like "Changes," "Brief Candles," and "Hung Up On a Dream," to make the track flower when you do it live, you have to have those extra elements. About half the album works wonderful just with a basic five-piece band, but the other half of it only works when you can reproduce every note that's on there. That's why it was so nice doing that show that you saw with Darian, and with Chris's wife [Vivienne Boucherat] doing some of the high falsetto harmonies that I overdubbed originally, and our normal drummer, Steve Rodford, doing percussion as well as extra bits and pieces. We get everything there – it's a lovely way to do it.

There was one Odessey and Oracle session you guys did for three of the tracks at Olympic Studios. What brought you over there during Odessey?

We couldn't get in to Abbey Road at the time; we heard that The Stones had done some recording at Olympic and we wanted to try it out. To my ears those tracks have a very different sound to them. They still sound good, but they sound quite different. The character of a particular recording studio and engineer, of course.

What room did you do most of Odessey and Oracle in at Abbey Road?

Abbey Road Three.

That's quite different than the room at Olympic.

Yeah, it took some getting used to.

The Zombies broke up right at the end of making Odessey and Oracle. Did you feel this coming during the recording of the album?

Well, Colin and I remember this differently, but I'm sure that Chris remembers it the same as me, in the sense that it was in the wind that the band was breaking up. We were based almost totally in the UK at that time, and we only ever had one hit in the UK. In those days, your [booking] fees were very much on the back of when you had your last hit. So the guys that weren't writers in the band, everybody except Chris and me, were just not making any money by the time we did Odessey and Oracle. The reason we wanted to do the album was because we'd become very frustrated with the way our producer had produced some of our recent singles. We thought that before he mixed them, that they were sounding very ballsy, really good and earthy; and then when he played us the mix we hardly recognized the songs sometimes. So Chris and I thought, "It's in the cards that we might be breaking up," because Chris and I didn't have the same financial constraints. We had very honest publishers. We later found out that we almost always had a hit somewhere in the world. But in those days, we didn't find out about those things until much later, and the royalties took their time coming through. Chris and I had been writing right from the beginning of The Zombies, so we had a really good stream of income. The rest of the guys in the band had got to the point where they were living pretty much hand-to-mouth. We were desperate to get our own ideas on record before we broke up. We recorded Odessey and Oracle, and we were all very proud of it. We thought it was great. But by that time our guitarist, Paul Atkinson, said, "Look guys, I'm getting married. If this first single from the album is not a hit, then I'm sorry, I'm going." Colin said the same thing, "I think I'm going to have to join him." There was no bad feeling in the band. It was just purely a commercial thing. Very shortly after that, for instance, Chris and I started working on a solo album for Colin [One Year]. Of course, the two of us immediately started putting my band, Argent, together as well. I'm so pleased, in a way, that we weren't happy with the production before Odessey and Oracle, because it enabled us to really make something that was unlike anything else that's around, I think.

Definitely. Ken Jones was your initial producer for all the material before that?

Yeah, he was. He was old-school, and a very good musician himself. He was quite a lot older than us. He didn't think in such a rock 'n' roll way. We loved the way he produced the first single, "She's Not There." This is another beef of mine, the fact that people almost never hear the original hit record now, because there was a drum part being added as it was being mixed down. It was four tracks going to one, going to mono, and that extra drum part is very important. The standard version you hear is just a remix that some fledgling engineer did much later at Decca. It's lacking that extra drum part that we put on as the song was being mixed down. Of course that drum part doesn't exist on the multitrack; it was only a 4-track record. When it appears in commercials, on film, or whatever, that the version they use is quite often the anemic stereo version, in my view. If you hear the original mono mix, which is actually on the Zombie Heaven box set that Alec Palao put together – because he knows everything about The Zombies – it sounds great. It sounds really earthy, and it's got a better groove. That's the record that was number one all over the world.

I think it's hard for people to understand there can be mix iterations of the same song.

Exactly. To continue that conversation about Ken, we loved the way he did that first session. All four tracks of that first session sound great. After that, because he was such an old-school producer, he had in his head, "What made this record a hit?" Whatever the "gimmick" was. He saw it as being the breathiness of Colin's vocals. Now Colin's vocals were fairly breathy, because of the heavy compression on that record. But that record was successful for many things. Colin's great vocal performance, yes, but the way everybody played together, the unusual nature of the songs, the sound of the harmonies, the sound of the rhythm track. Everything was just trying to make the song sound its best, rather than being analytical and saying, "Oh, we've got to emphasize the breathiness on Colin's vocals." We felt that he did that a lot after that, and to the detriment of the fullness of the production on the record.

Have you ever had a chance to go in and remix some of those sessions that you were unhappy with?

We had a couple of goes. One of the problems is that the sessions were all done on four tracks, sometimes bouncing instruments together. We did a cover of "Goin' Out of My Head," the Little Anthony [and The Imperials] song. We loved the harmony arrangement of that. We asked Ken, a very good arranger, to do a little brass arrangement for us. We described what we wanted. But then he wouldn't let us into the studio while it was going on. He bounced down the vocals, and instead of what was in our head, which was a very full vocal harmony sound – the sort we did later on Odessey and Oracle – he emphasized Colin's voice. It was a premix on there between the brass, the harmonies, and so on. It meant that some tracks just can't be extricated. I remember that one was a huge frustration for us. But here we are; it's just how it is really, and now those things exist. I remember we did "Is This the Dream?" and we felt when we left the studio, before Ken mixed it, that it sounded really stomping. When we came back and heard it, we couldn't believe what had happened. Colin said, "Was that the track we recorded?" I don't want to go back and revisit everything we did. That was then. It's done now.

Well, you've done quite a bit in the meantime!

Yeah, exactly.

I think you and Chris White getting your production chops together and saying, "Look, we can do this on our own and express our own vision in the studio," is interesting.

It was, and it felt very natural. Of course we did have the benefit of working with Geoff Emerick and Peter Vince, who were brilliant engineers. We just took that for granted, but the sound was great. Geoff Emerick doesn't give many people a name check in his book [see sidebar -ed.], but he gives us a name check. He says something about how we were one of the few bands at the time that wasn't just copying The Beatles. I was so knocked out that Geoff said that. It's very sweet, because he's a great engineer. We were never trying to copy anything specific of The Beatles, but we thought of ourselves as trying to be The Beatles when we recorded. If you go back and hear "She's Not There," it doesn't sound anything like The Beatles. It goes through the filter of your own creativity and consciousness. It comes out as your own thing.