David Gilmour met Unicorn at a wedding, and asked to sit in on "Heart of Gold" with you guys. Was there anything else you played together at that event?

No, he just asked if we did that. He came up to me and said, "There are numbers out there I didn't recognize. Are they original songs?" And we said, "Yeah." And he said, "Do you do 'Heart of Gold?'" And we didn't actually do it in the act, but it's something we all jammed on. He asked, "Can I come up if you're going to do that?" He came up, we did it, and at the end he said to me, "Give me your phone number." He didn't say why, but I gave him my number! A week later he phoned me up and said, "I just had this studio put in my house. I wondered if you guys wanted to come and put down some of your original songs so you can demo them. It's new and I'll be experimenting, but I won't charge anything for it. Do you want to do it?" No, why would I want to do that? Get lost, you nasty man! [laughter] So, we all turned up there with a van for the gear, pulled up out in the back, and he said, "You can bring in what you like, but do you want to have a look at what's in here? You can use any of it." I walked in the room, and he's got them hung up on the wall like that... Jesus. A '60's [Fender] Strat, a '53 [Fender] Telecaster, and a Fender P Bass! "Yeah, okay. We'll use those."

Those will do!

He had two [Fender] Twin Reverb combo [amps]. He'd changed the speakers in them from the Fender speakers to Celestions; he preferred them. Bass I DI'd. There was a Wurlitzer electric piano in there. I remember it was an American one, because he had a transformer to knock it down to 100 [volts], because we're at 240 [volts]. There was a lovely maple Ludwig kit, and he said, "Pete [Perryer, Unicorn drummer and main vocalist], you can use that." At Christmastime we'd done some live BBC Radio [appearance], and David had said, "Do you want to take the Ludwig kit? Sounds better than your Trixon." So, Pete borrowed it, and I think I phoned David up to say, "When do you want the kit back?" I happened to mention, "It's Pete's birthday." And he said, "Tell him to keep them. I've been wanting to get a Gretsch kit." I went 'round to Pete's house. Pete was one of 12 children, and it was like bedlam in his house. He was still in bed, and I said, "Hey mate, you've got a Ludwig kit." He said, "What do you mean I've got a Ludwig kit?" I said, "David's given you the Ludwig kit." And he went scratching, "Have I woken up or...?" [laughter] All Pete had to do was buy some cymbals. That's the sort of guy David Gilmour is.

Back to the playlist... we've gone from Gilmour's productions for Syd Barrett into meeting you guys at the wedding. I tucked in Monty Python's "Gumby Theatre." You'd mentioned Gilmour played that during a session, as an icebreaker.

It wasn't just the "Gumby" thing. It was a matter of watching Monty Python again, after a day's recording that had gone really well. His girlfriend [Ginger Hasenbein] cooked us a meal. I remember meatloaf – I'd never had meatloaf before. She was American, his first wife, Ginger. It was before she was his wife. We had that and the strange-smelling cigarette we puffed. David had this early version of a video recorder and played Monty Python. When you see it the second time, you spot things you hadn't seen the first time. I think he was laughing so much at the way we were laughing. A magic moment. I can picture the room and everything. He has a great sense of humor.

Toward the end of the Unicorn tracks on the playlist, I included Unicorn's original version of "No Way Out of Here." Then there's a Steve Miller track included from Fly Like an Eagle.

Yeah, he really liked that album.

Rebecca Turner: Oh, "Rock'n Me."

He liked the feel of the album. One of the things he pointed out to me that he liked, as he told me, "It's nothing they've gone to town on. They're just playing."

The Unicorn song, "British Rail Romance," is next on the playlist because David produced half of that album [One More Tomorrow].

He produced about four tracks. He basically finished it, and EMI Harvest [record label] said, "You need a single." The managers said, "We need someone that's had success making singles." They asked a few people. Muff Winwood was interested. He'd had some massive hits, but with people like the Bay City Rollers. He also had a big hit with the Mael brothers, Sparks, with "This Town Ain't Big Enough for the Both of Us." We met Muff and he was a really nice guy. Because Steve Winwood was one of our band's heroes, we spent a lot of time talking about how great he was and everything. I remember one time Muff got fed up, and he said, "He can't write words you know!" [laughter]

RT: Did Gilmour say a lot, or was he a man of few words in the studio?

Oh no; he didn't force anything on you. He'd make suggestions, but as he said on his notes on Laughing Up Your Sleeve, he wanted to make it the best possible version of how we wanted it. I remember once – I think it was when the Too Many Crooks album was nearly finished and was at the mixing stage. He always used to phone me up to find out what Ken [Baker, Unicorn guitarist and songwriter] was thinking. He was going off on a tour and he said, "I've gone to the States. Ask Ken what he thinks – I'd like to take the tapes with me and mix them while I'm using the studios out there." So, I phoned Ken up and he said, "No way. I'm not having my songs done when I'm not there." Ken and Pete were like that. "No, you've got to be there when your music's being mixed." Definitely Ken – you probably noticed that there's not lots of reverb and echo used on them. They're pretty dry; Ken hated "productions." He wrote most of the songs, so he got the final say. In fact, what we used to do when we were mixing them, Ken and Pete would go off somewhere, play pool or go to the pub, and me and David would be sitting there. He'd get to a certain point and then say, "Go and get them." [laughter] I'd find them in the pub. They'd come in and say, "Yeah, that's all right. But can you do this, this, and this?" That's how it worked.

Something else that I was wondering about with the recordings from Laughing... those demo versions you and I mixed: were those mixed back at that time?

I don't remember ever having any mixes from there. I don't even know if they were mixed.

It was more of the practice of laying it down and figuring it out?

Yeah; putting original songs down. He must've done some rough mixes, because he played them to [Pink Floyd's manager] Steve O'Rourke, and then he phoned me up and said, "I played the songs and he'd like to offer to be manager." We spoke to Steve and he said now he wanted to do it. Rather than go to the record company and have them pay for the recording, he said that he and David would pay for the recording in proper studios. Then we could get a much better deal with the record company, because they didn't have to pay for the recording. I know that when it came to an end, when we got called into the office and they said, "There's nothing we can do with you anymore." In fact, Steve didn't even turn up. He sent his assistant manager in there. I was the only one married with kids, and I remember saying, "Oh. Well, we'll have to share out the money." He said, "Actually, you owe us some." We were on a wage at the time. "But we'll give you a wage this week, and that's it."

RT: Wow.

Yeah. We walked out of there, went for a coffee, and we sat there. Pete said, "I can't understand why nobody said anything." I said, "Well, you didn't say anything either, did you?" We were so stunned. We thought we were going to be talking about making the next album. While we'd been in there, he played us a punk record by The Damned. He said, "This is what people want now." He said, "What do you think of it?" I said, "It's awful." I don't think David had anything to do with it. It was quite a blow. Our music was so old-fashioned, really, by the time. Someone asked us about going to America. I was keen – even my wife was keen to going. And [then] that was it.

Around this time,in 1973, you and Pete were invited to play with Kate Bush on her first visit to David's house to track demos.

The only one that she released was called "Passing Through Air." It's the B-side of "Army Dreamers." That's the only one of the songs we did that I remember, because it came out later [in 1980].

How did playing with Kate come about?

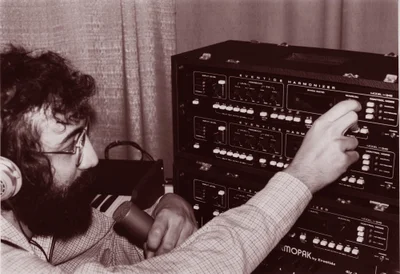

David phoned me up and said, "Would you and Pete like to come up?" Our tour manager was this guy named Ricky Hopper; he's the guy whose wedding we played at when we met David. When we signed with David and his manager, Ricky became our tour manager. He was a very brainy guy. He had a friend at university, and he said, "He's got this sister. She's only 15, and she's like Joni Mitchell. She writes these songs." He was always on about it; I didn't ever hear any of it. He obviously was having a word with David about it, and David said, "All right, get her to come to the studio." Then he phoned me up and said, "Would you and Pete come up to the studio? That girl Ricky keeps on about is coming in. I wanted to do some demos with her." He said, "Might not be any money, but you'd be helping her out." We said, "Yeah, great." Me and Pete went up there and she turned up. She had long, dark hair and was slim – she looked like a schoolgirl. She said, "I've never played..." All she'd ever done was play in her bedroom. Her brother had recorded her on a cassette player. She'd never played with musicians before. She said, "I don't know what to do." I remember she sat there at the piano and I was next to her – I felt like her dad. We said, "Play it like you're in your bedroom and we'll play along." David set up some sounds. Pete was on David's new Gretsch kit, because Pete had his kit. I didn't even take a bass; I used one of his basses. It's me on bass, Pete on drums, David on guitar, and her on her upright piano; the one that on Laughing Up Your Sleeve was slightly out of tune.

Oh, yeah. What Unicorn track was that?

Um... was it "The Farmer"?

It was.

What was really nice was when "Passing Through Air" came out years later; she sent us a check, me and Pete, for 100 quid each. And at the time neither of us had any money. I think David told her manager, "You upset those guys. They did it for nothing." I think we tracked four, maybe five songs. We listened to it and she was knocked out. She kept thanking us. The next time I saw her was when we were recording [Unicorn's] One More Tomorrow in Pink Floyd's studio in Britannia Row. She came in there to see David about something and he wasn't there; she was a bit nervous. I said, "The keyboard player in Floyd [Richard Wright], his keys are all set up in there. Do you want to have a look at it?" She said, "Oh, yes." I took her in there and she had a light go on different sorts of keyboards. Then David came in and she saw him about something. I didn't see her again. Then she had the hit ["Wuthering Heights"]. I was watching her on the telly, and the guy was interviewing her, saying how different she was. She said, "I'd really like to thank a band called Unicorn." It was just after we'd got the sack. It was strange. I never spoke to her or saw her again until Ricky Hopper, the guy whose wedding we played at, died, and me and one of the roadies were going to the funeral. At the time, I had a job as a mobile library manager driving a big truck of books around little villages. Wonderful job. I was talking to one of my customers when she phoned, and my assistant said, "He's busy at the moment. Who is it?" She went, "Who?!" So, I said, "Oh, hi, Kate. Long time no see." She said, "Yeah. You're going to Ricky's funeral, aren't you? Can you find out for me who the funeral director is? I'm not going to come, but I want to send some flowers." I said, "Yeah, I'll do that." We talked a bit. She said, "What are you doing now?" I said, "Mobile library manager." She said, "Oh, what a lovely job." I said, "I can still see you walking into that studio. You looked really nervous." She said, "Nervous? I was bricking it." It's an English term for sort of...

RT: Shitting bricks?

Yeah. We chatted a bit and that was it. My assistant looked at me in a different way for the next couple of weeks!