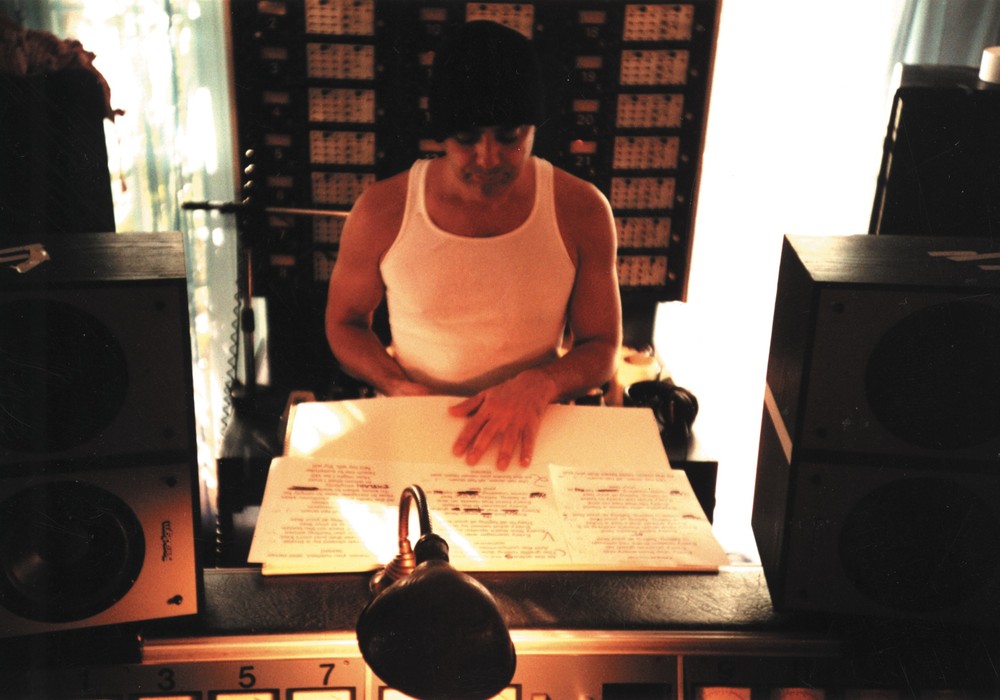

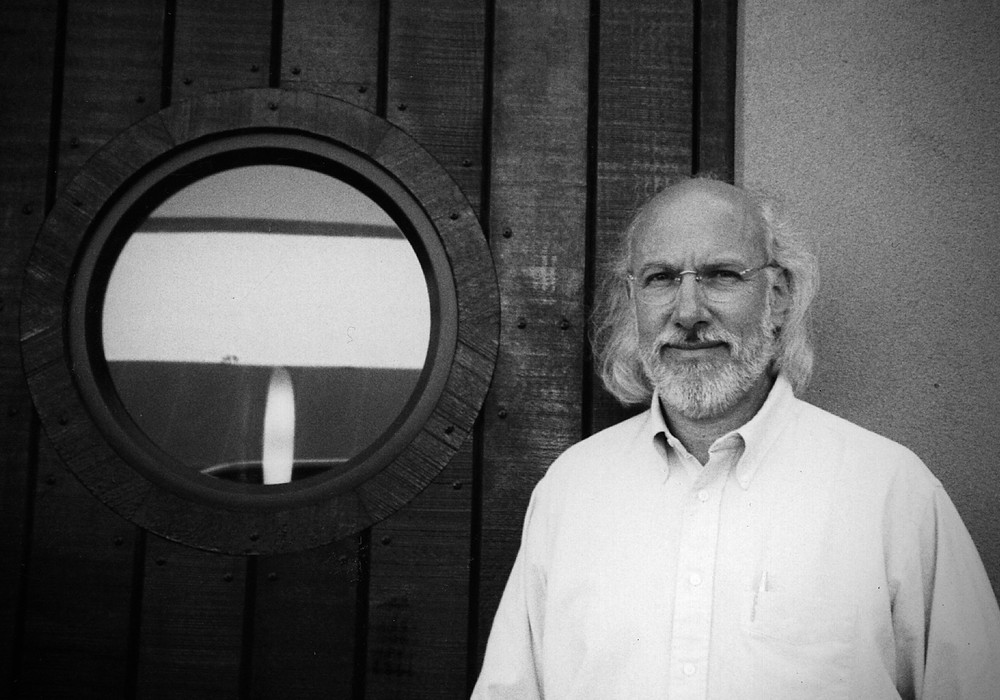

As the leading force behind the popular instrumental group Snarky Puppy, bassist/producer/composer Michael League has plenty on his plate simply by keeping up with the band’s prolific output. Then throw in a record label, a festival, and producing records for artists such as the late David Crosby and the amazing Susana Baca [Tape Op #32]. How does he do all this?

We caught up with Michael as he was wandering a desert in Spain where he has his studio [Estudi Vint] on a rare “day off” to find out more about his methods, as well as Snarky Puppy’s fantastic Grammy-winning album, Empire Central, which was recorded live in front of a studio audience over eight nights and featured their “musical godfather,” the late keyboardist Bernard Wright.

Congrats on Empire Central. I finally watched a couple of music videos from the performances and recordings. I didn't even know it was that many people playing music together.

It's a lot, yeah.

You're lucky, because there's only one bass guitar, right?

Well, there's one electric bass, but at any moment one out of five people could be playing bass. There are key-bass players and baritone guitars. You never know where the sound is coming from!

How many musicians did you have playing on that?

There were 19, or 20 with Bernard Wright sitting in.

I know you've done a number of albums with an in-studio audience. Has that been a conscious thing to keep the performance aspect of the music happening?

Yeah. The heart of it is that the band is a live band. That's always been where the energy and magic has occurred, when we've been playing in front of people. We were doing the normal thing, going into the studio and making records. We did this for three albums; the first six years of the band was like that. At a certain point there was this thing of, "How can we represent the live experience in an album in a way that isn't a 'Live at…' record?" There's the whole thing of dealing with the sound of this massive PA. How do we mix it so that it sounds beautiful? It seemed the best of both worlds would be to make a studio album live and bring the audience into the studio rather than bringing the studio to the audience, which is what most live albums are. That's how we came up with this concept. I guess we first did it in 2009 with Tell Your Friends. We stuck with it and tried to make it better every time. We did it on Ground Up, We Like It Here, Sylva, and two Family Dinner records. At a certain point, we got to feeling like we couldn't do this every time. I believe strongly that when you change the process, you change the product. I also don't like this idea of finding something that works and doing it over and over again. It starts to feel more like McDonalds than David Bowie. I thought it would be good to change up the process. So, we did two studio records, but we did each one of those in a different way that was unconventional. Then we did Live at the Royal Albert Hall, which was a more traditional live record.

Right.

After six years of not using this format, we went back to it with Empire Central. It's coming back into our comfort zone, in a certain way. Then, of course, we did many things with this record that we've never done with any of these live in studio records. Every time it has to be different. That's what we try to do, even when we play live.

What were the main differences in the process for Empire Central?

Empire Central is like the live version of our last studio record, Immigrance, in a certain way. The idea behind Immigrance was that we were going to have everyone in the band playing live, but we'd never have more than one drummer playing at a time. On [the previous album], Culcha Vulcha, we had two drummers playing in unison at any given moment. On Immigrance, we had one drummer playing the verses, one drummer playing the choruses, and one drummer playing the solo section. That's what we did live on Empire Central. The drummers are switching on the downbeat of every section.

Holy shit.

Yeah. If we're making a studio album, there's the luxury of changing snares for the chorus, or changing bass drums, depending on what we want for each section. Of course, when we play live with a single drummer, we don't have that luxury. Rather than it being this super frivolous idea of, "Let's have everybody on every track," because we can, the idea...