Imagine a studio where they shut the doors 40 years ago and left everything as it was. It's just not possible, right? Think again. Over the last year Nic Jodoin, with partners Brittany and Justin Barsony, have reopened Valentine Recording Studios — a place that has been closed up and unused since around 1975. Opened in 1964 by engineer Jimmy Valentine, the studio hosted sessions by artists as varied as Bing Crosby, the Beach Boys, Burl Ives, and Frank Zappa. In 1975 the studio basically closed its doors after an extensive renovation.

Nic Jodoin gave us a lengthy tour, and we met up with Jimmy's daughter, June Valentine, who runs Metropolitan Pit Stop next door to the studios. Valentine Recording Studios is a trip back in time. It's awesome to see it brought back to life and making new records for artists like The Coathangers, Curtis Harding, The Night Beats, and Nick Waterhouse.

-

Studio B's UA 610 console in mint condition. Note the custom talkback mic and formica desk.

Studio B's UA 610 console in mint condition. Note the custom talkback mic and formica desk.Photo 01 of 17

Studio B's UA 610 console in mint condition. Note the custom talkback mic and formica desk.

-

Close up of Studio A's MCI console. Nice red knobs!

Close up of Studio A's MCI console. Nice red knobs!Photo 02 of 17

Close up of Studio A's MCI console. Nice red knobs!

-

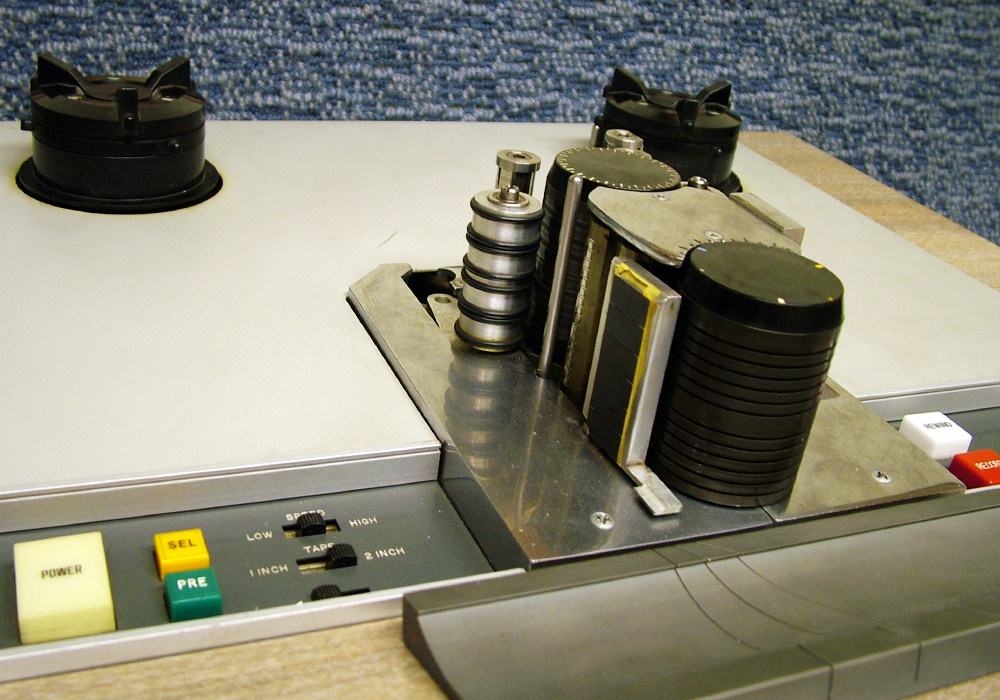

Close up of the Stephens head stack and roller assembly.

Close up of the Stephens head stack and roller assembly.Photo 03 of 17

Close up of the Stephens head stack and roller assembly.

-

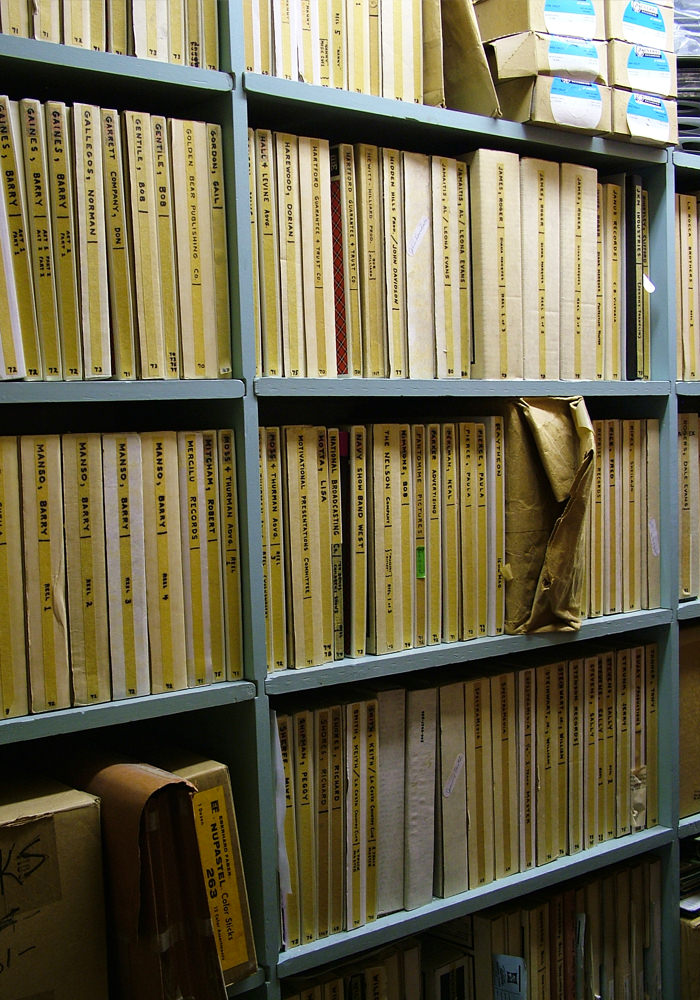

The tape vault.

The tape vault.Photo 04 of 17

The tape vault.

-

Studio B Control Room.

Studio B Control Room.Photo 05 of 17

Studio B Control Room.

-

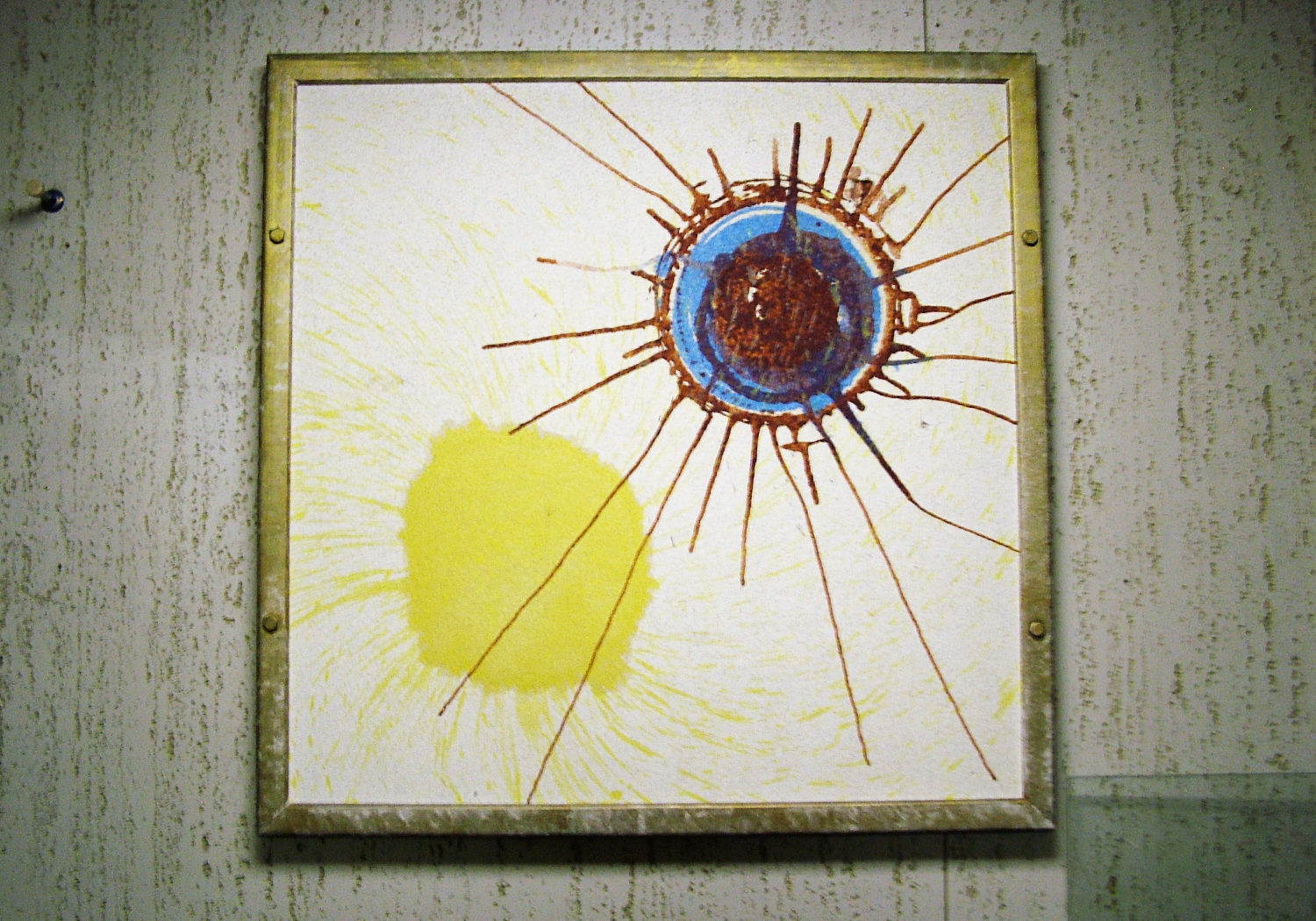

Jimmy Valentine even made custom artwork for the studio.

Jimmy Valentine even made custom artwork for the studio.Photo 06 of 17

Jimmy Valentine even made custom artwork for the studio.

-

Studio A's Quad-Eight Sidecar.

Studio A's Quad-Eight Sidecar.Photo 07 of 17

Studio A's Quad-Eight Sidecar.

-

Even the TV and remote are vintage. Note the Altec Lansing promo shot of Valentine, circa 1960's.

Even the TV and remote are vintage. Note the Altec Lansing promo shot of Valentine, circa 1960's.Photo 08 of 17

Even the TV and remote are vintage. Note the Altec Lansing promo shot of Valentine, circa 1960's.

-

UA console detail.

UA console detail.Photo 09 of 17

UA console detail.

-

Studio A Control Room.

Studio A Control Room.Photo 10 of 17

Studio A Control Room.

-

Photo of Studio A.

Photo of Studio A.Photo 11 of 17

Photo of Studio A.

-

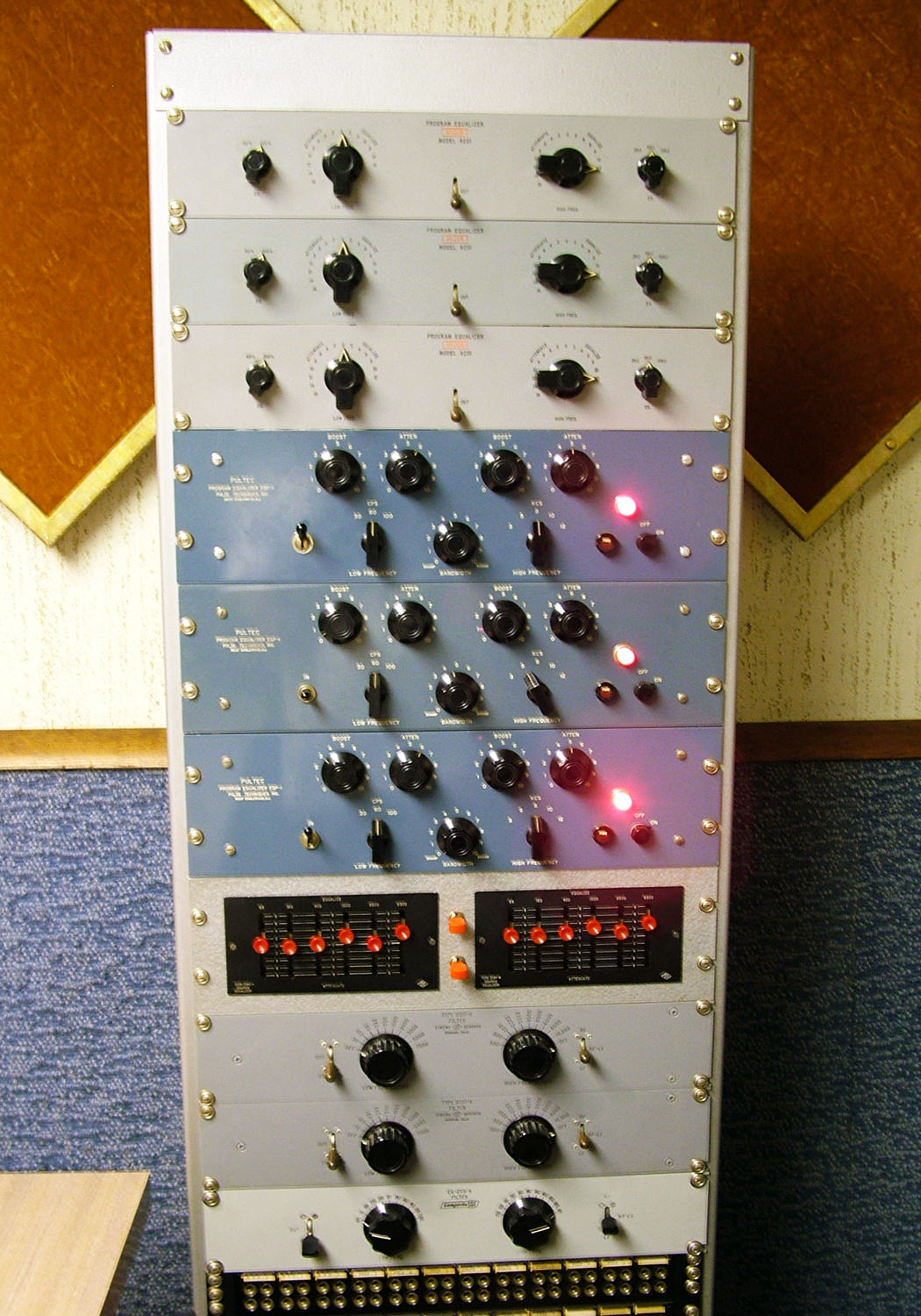

Studio B EQ Rack

Studio B EQ RackPhoto 12 of 17

Studio B EQ Rack

-

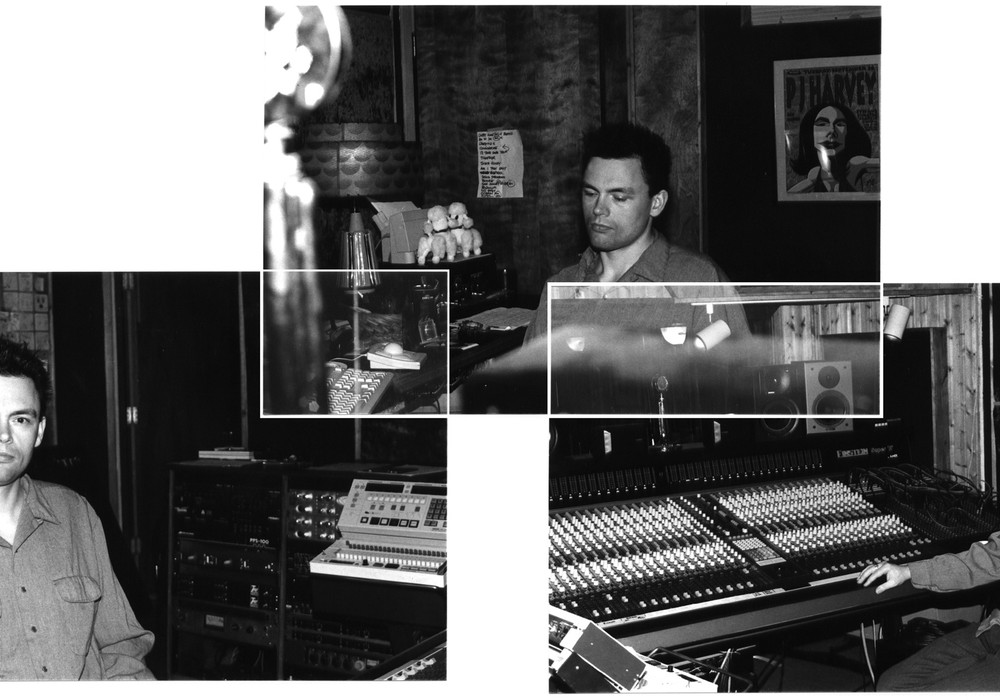

Maintenance tech, Corey Creswell.

Maintenance tech, Corey Creswell.Photo 13 of 17

Maintenance tech, Corey Creswell.

-

Studio B mixdown and multi-track machines.

Studio B mixdown and multi-track machines.Photo 14 of 17

Studio B mixdown and multi-track machines.

-

Starbird mic stands are the best!

Starbird mic stands are the best!Photo 15 of 17

Starbird mic stands are the best!

-

Musicians-eye-view from Studio B into control room.

Musicians-eye-view from Studio B into control room.Photo 16 of 17

Musicians-eye-view from Studio B into control room.

-

Dubbing room.

Dubbing room.Photo 17 of 17

Dubbing room.

LC: Jimmy Valentine was the original owner?

He was the owner, and the one who built it.

LC: Was he an engineer as well?

Yeah. He worked at Capitol. He also worked in the sound effects department at NBC in Burbank.

LC: He was one of the first people to build a studio out in the Valley.

Pretty much.

LC: When did the studio open up as a commercial facility?

The story is complicated. In '46, he started Valentine Sound Recorder. I think he started it in Washington, D.C. Then he moved to Los Angeles and built a studio in the back of his house. Then he bought this building and they opened up in 1963. This was a doctor's office and he added to it. He started with a little studio and later added a room [Studio A] in the back.

LC: Was the studio in the front of the building, Studio B, the original, small one?

Yeah, but it didn't have that board, the Universal Audio 610-A. It's from '64 and was made for him, for the larger Studio A. We still have the bill of sale and all the specs that he asked for. He was definitely into big bands, and his eye was on movie studios and doing projects for film. He had all the gear set up in the back [Studio A]. Then they renovated the back studio and finished it in '75, but he never fully connected it.

LC: So the renovated Studio A never got fully operational?

Never. He lost interest. We got stories from somebody who was hired by Jimmy when he did the Beach Boys sessions here. He was already in his forties, and he hated working overnight with a band that would work on one song for two or three days when he was used to doing ten songs in four hours. He didn't really like how the creative process had been developed.

LC: What was this place like when you first saw it?

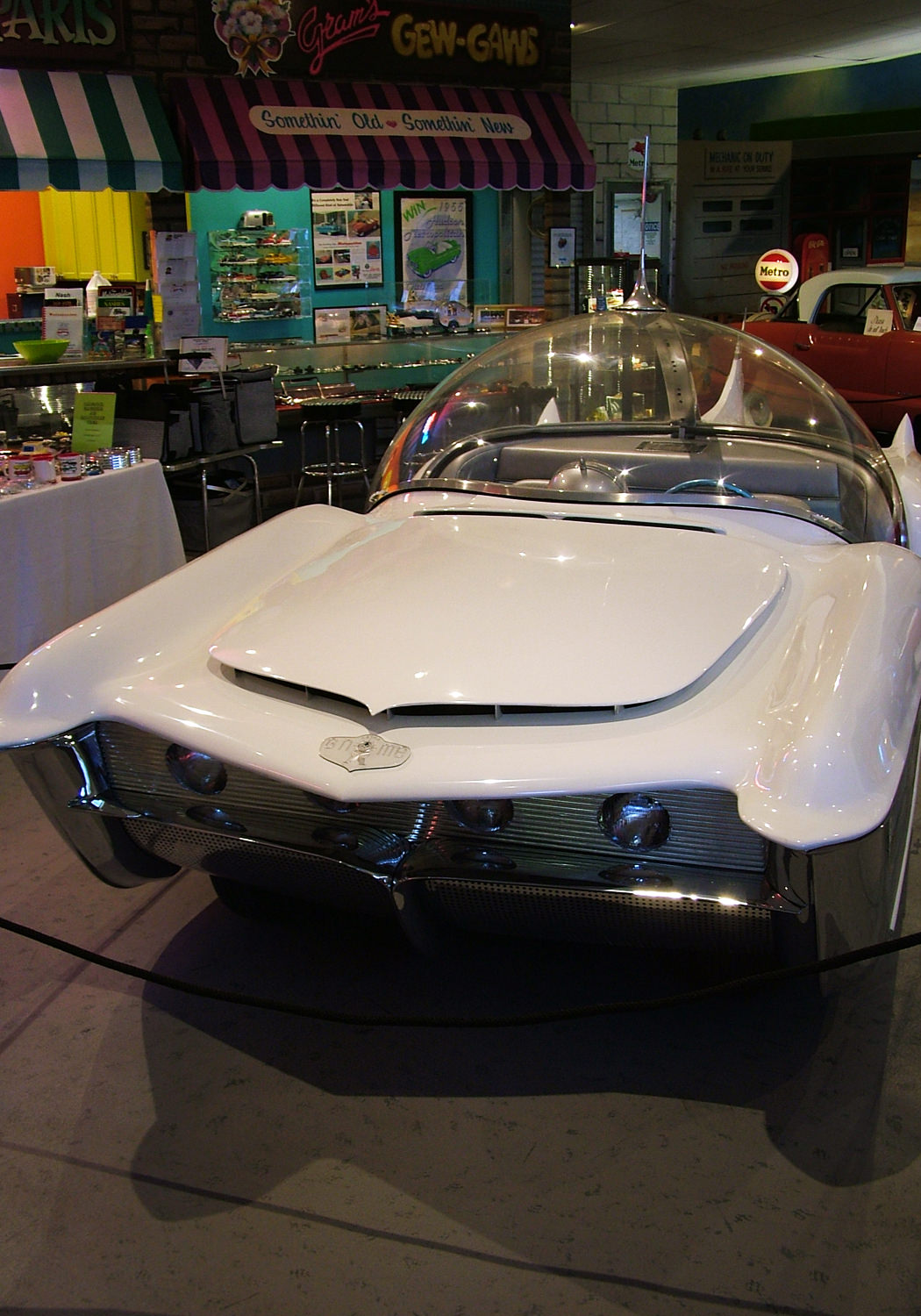

When I walked in here the whole place was filled with car parts and family items. He had started his car business next door. He'd bought a Metropolitan Nash and started fixing it up. When he'd find parts, he'd buy everything there because it's a rare car. Then people started calling him for parts. He got into it and became the biggest distributor, and then he even opened up a museum next door. In the back there was a parted out Rambler. They basically used the tracking rooms for storage.

LC: How did you get involved in reopening Valentine Recording Studios?

Through a publisher I know, who I sometimes do licensing with. We were having lunch and she said, "My childhood friend's grandpa built a studio in the '50s and closed it in the late '80s." She had all the dates wrong. She's said they didn't know what to do with the building. "Maybe you should come and check it out. Maybe there's some equipment you'd be into." I was like, "The '80s?" Walking in was a huge shock. I told Justin [Barsony], my partner [and part of the Valentine family], "You're not selling any of this. It would be a crime. They'll part it out."

LC: Is the family interested in having it running as a commercial studio now?

Yeah. The reason why they kept it was out of respect for their father's love. They know how important it is. They can tell the history of it, and were a part of this history themselves. They said, "Some people came to see it and were interested." But everybody said, "Oh, it's going to cost so much money to change things." Everyone was looking at it from the commercial side. I said, "No, there's a scene with bands that would totally be into it and can afford it. It's their dream to be able to record like this."

LC: Is everything operational in the studio now?

I can't tell you that the studio's 100 percent operational. There's a lot we need to do. But for projects, if you want something, it's a day away from being ready to go. The board and everything works. I had a session yesterday with Brian Bell from Weezer. Today Ethan Johns [Tape Op #49] is coming to do a writing session. I've got Curtis Harding working in the back on a soul record. I'm producing that. It's really cool and really fun.

LC: He's great. I saw him on tour.

We're going for a total Al Green thing with strings and horns. I love it.

LC: I can run 16- or 24-track at my place. People say, "We gotta work on tape." Then, we get in there, they don't understand. "Okay, start on track 1 and fill them up!" I'm like, "No, no!"

I recorded this weekend. Curtis wanted to have a bass player who worked on the last album come and record. He's really good, but it was definitely one of those, "Hey, give me another track." It's like, "There're no other tracks!" It's 16-track, 2-inch, and I'm keeping that other track for something. "Let's get this take. It is what it is." It's an old machine, from the early '70s. Punching in is a total bitch.

LC: It just takes more planning ahead. "Where does everything go?" You need to leave open tracks to bounce down to.

You also assess who you're working with. "Oh, he's not that good of a player," or "He's good, but he's not consistent." So you need three tracks, and instead of punching in onto one track, you punch in onto another track, and then bounce it all down to one track and comp it yourself. It's easier to do that way. It's a lot of planning and scheming. I like to do that.

LC: Do you have Pro Tools set up in here?

I have Pro Tools on my laptop, and I have a couple converters I bring in and out. I'm not opposed, but it's not set up for Pro Tools. It's not part of the set up. The intention is just, "Sure, we have the converter." We can patch it in, but we're not setting up anything around Pro Tools. No computer towers, no nothing. It's not part of the idea, you know?

LC: There are speakers in the back of the control room in Studio A.

It was all set up for quad.

LC: What is the console?

It's an MCI 416. Custom made.

LC: The patchbay panels are all set up for connecting to the tape deck.

It's thought out. On the patchbay I can patch so I can bypass my mic pres and use the mic pres in Studio B from back here. Both rooms are connected together. It's all patchable. Jimmy really thought about everything. I wish I could have met him.

LC: It's such a visual studio. Part of one of the Aquarius TV shows was shot in here.

Where Charles Manson gets in a fight with Dennis Wilson.

LC: That's just bizarre. That's recreating some strange history.

I was here being the watchdog. They had to ask me, "Can we move this?" It breaks my heart when something breaks here.

LC: Did you start doing records in here immediately?

Yeah, we did The Coathangers right away. They were the first band. I thought it was going to be the perfect thing; they're kind of punk rock, it's their first experience in the studio, and the studio's amazing. We needed some time still to get things routed, so whatever issues we had they'd be patient with. I worked out a deal where, "Look, there'll be a lot of little issues and you'll have to be patient, but you'll get to use an amazing studio." We got it going and it was amazing.

LC: Was this Voice of the Theater speaker in the live room so they could pipe music in here?

They were big bands, so they'd listen back to the recording through this because they didn't have headphones for everyone. Nick Waterhouse had Leon Bridges as a guest on a song and we tracked in here using the speaker — they were doing a duet together. You've just got to make sure it's not too loud.

LC: Are there echo chambers?

I asked the family about the echo chambers. We were looking everywhere. Finally, I found architect plans while we were cleaning up and saw they were in the ceiling. They sound amazing.

LC: Was there a microphone and speakers in there?

There was a speaker, but we had to put in a mic; an old Altec. The Coathangers loved to go in there and do backup vocals. It was pretty fun. We've got two chambers, the plate reverb [EMT 140], and there's an old '60s spring reverb.

JB: So the family still owns this building. Are you leasing it?

I'm partnered with the family. They're part of everything. I met the family and said, "You guys have to do something." They didn't know anything about the gear, and they didn't want to destroy it or undo it. It's their family heritage. It's the dad's passion. The dad and mom spent their life here. The kids grew up here. Once you go and see the cars next door, you'll get that this is all their life. That era is part of their heritage.

LC: Are people getting excited about working here? You're keeping it very busy?

Yeah. I'm exhausted. It's been awesome.

LC: There's a movement these days to say there's an authenticity in the way one might work in the studio. "We did it to tape" or, "We did it all playing together."

There is something to that. I think a lot of bands now, like The Coathangers, that's what they've built themselves on. It's real. Playing live, touring, having a hard time, but still believing and doing it. They have their own style. It speaks to people. I like it.

LC: It's got to be the right project, and the right engineers and all.

That's important for this place. The way I see it, I try to curate. There are people who are like, "Oh, it's great. I want to come record here." I try to find out if they're really right for the place. If they're just in love with the look, maybe they're going to be like, "What the fuck is going on with my headphones? Why does it take so long? Oh, we have to wait for the machine?" Then the attitude starts and it's not fun. They're not going to get what they want. Some people are better off working in Pro Tools. We just did an old school jazz trio recording with Jon Batiste on piano, with upright bass and drums. It was amazing! The room seems built for a jazz ensemble.

LC: I can't wait to see what kinds of artists like working here.

It's not just an old, dusty place. It's living. That's something I see when everybody comes in and spends time. It's a world that becomes their existence. You become attached to it, and it's yours. You defend it. You protect it. I was in bands and I toured, and there's always this hope that you'd go into a small town, like a pawn shop or something, and find a rare guitar for nothing. I feel like that's what just happened to me. We opened up faster than I thought we would. Now it's going, and everybody's loving it.

www.valentinerecordingstudios.com

The Coathangers' Nosebleed Weekend was the fifth album for this rocking trio from Atlanta, Georgia, and the first album to come out of Valentine Recording Studios. Nic Jodoin produced and engineered, with assistance from Chris Maciel. We asked the band (Minnie Coathanger, Crook Kid Coathanger, and Rusty Coathanger) about their experiences at Valentine.

How did you choose Nic Jodoin for recording/producing your album?

We met up with Nic at a diner in L.A., thanks to our manager Geoff Sherr. We got along quite well. Then we recorded a 7-inch together and decided this was a working relationship we definitely wanted to pursue further. Nic just got us and had a vision for us.

Did the unique, retro vibe of Valentine inspire you as players, or stylistically, at all?

It definitely had an effect on everything! We worked harder and played tighter just knowing how lucky we were to be there recording where legends had stood. We pushed ourselves harder as players.

I heard you sang in the echo chambers! What was that like?

Oh, man [that was] our favorite part! Minnie used to go stand in the hallway when we were listening back to mixes, come back, and say, "Maybe we should run a take through the echo chamber." Every time. It became a running joke. We loved how dreamy and magical it made everything sound! We went up there a lot. It was also the warmest spot in the whole studio, so we always wanted to be hanging out up there.

Do other studios look too modern and boring to you now?

In general, we prefer to have a warm atmosphere when we record. We toured several studios with Nic, and all the super high-tech studios we instantly rejected. It's too much. That kind of modern atmosphere, with computers all over the place makes the technical part too prominent. The vibe of Valentine is definitely unbeatable. You just feel like you're making something awesome when you are in there. We are very lucky to have had the opportunity to create there.

Dad actually started recording at home. He worked at Capitol Records when he first moved out here to L.A. He added on to the house and was recording in our home for the first several years. When he bought this building, it was 1963 and I was already ten years old. Then he added on to this building too. There was only the little front section, which was a doctor's office. I would come in occasionally after school while the construction was going on, and I have vague recollections of that. Later I would come over, sometimes when there were artists recording, but I didn't get too much opportunity for that because they were either there when I was in school or they'd be there for night sessions. My dad passed in 2008, and we kept thinking, "What are we going to do?" For years my brother [Jimmy Jr.] and I had this dream of getting it going again. We're both busy, because I was already immersed here [Metropolitan Pit Stop], and my brother's an hour away, in Palmdale, with a career at Lockheed. Not only was there so much equipment in there to deal with and to move out, but then we had a flood and the carpet in the front part was soaked. It had dried out and we'd brought specialists in to try to suck some of the water out. They had to take all the carpet out in front and try to do something to the floor. They did some painting and brought it back to life. It was really exciting to see it.