You grew up in Santa Monica, California. Did you have a childhood that was filled with music?

My mother had a piano, and I couldn't stay away from it. I played by ear, and I thought I could play nearly anything I heard until my parents gave me lessons. [laughs] I hated them, and I quit playing piano. This was when I was five or six. I still loved music, but that ended my playing the piano.

Your father, Robert Landee, was a musician?

No, he was an electronic engineer. My mother and father divorced, and my father remarried in 1957. He married a musician, Janie McFadden. She had a trio and played Las Vegas. She had a contract with RCA Victor Records and recorded at RCA Studio A in Hollywood in 1964. So, that was another real music connection.

Did you attend that session?

Yes, I was at her 1964 session, which was the first ever in the then new RCA Studio A. In fact, the RCA staff hadn’t completely moved in yet. Twice a mic on the strings failed and someone had to run to the old RCA studio, which was on the other side of Vine Street, and get a replacement. It was live to 3-track. The producer was Neely Plumb, and I think the engineer was Dave Hassinger, but I was never able to confirm that. At the time, I didn't recognize any of the session players. They had piano, bass, drums, and two guitars on one channel, twelve strings on another, and Janie's vocal on the third track.

You grew up with another musical family, the Dragons.

I didn’t meet the Dragon family until 1961. I met Dennis Dragon [The Surf Punks, Tape Op #69] in September of that year, during the first week I was going to Santa Monica High School. He lived in Malibu, and at the time Malibu kids would go to Santa Monica High. We were both applying for the school’s sound crew because we both thought it would have something to do with recording music. It didn't. It had to do with running PA systems for football games and pep rallies. That was truly the bottom of the barrel. There were special requirements, like, "You’re going to have to work in the rain." [laughs] So, we didn't much get into that. I got to know Dennis, and as soon as I could drive I was regularly going to their house in Malibu. That's how I met his father, Carmen Dragon, and the rest of the family.

What was the first record you remember falling in love with as a kid?

Harry Belafonte’s Calypso. The sound of that record was like nothing I'd ever heard. It was fantastic for its time, in “glorious monaural” and all that. It was a great record, and was the first LP to sell a million copies.

Back in those days, record companies often didn’t credit producers, much less engineers, on the albums. Were you able to learn who worked on it?

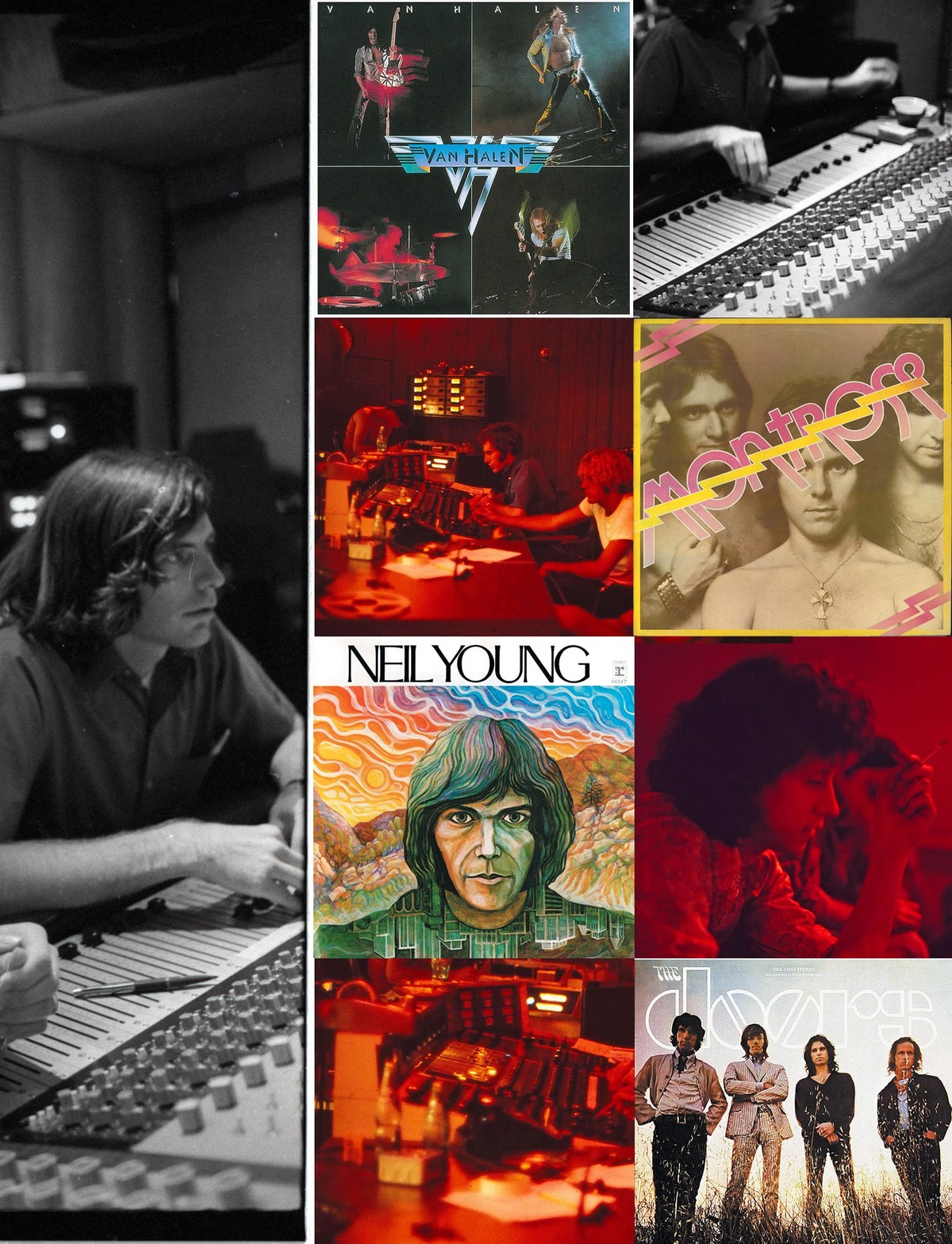

No. I later found out it was done at RCA in New York, but that's all I ever found out about it. At that time, my father was a chief engineer at Collins Radio Company; they built radar and communication equipment. After he married Janie, he would bring recording equipment home, like an Ampex 350 recorder, an Altec mixer, and Telefunken U 47 microphones. In our living room, I did my first recordings. We had three microphones. It was Janie singing and playing piano, accompanied by a string bass player. In fact, [I recorded her playing] the seven-foot Steinway B piano that my father sold to Ed [Van Halen] in 1985. It’s the same one that we used on Van Halen’s “Dreams” and that Andy [Johns (Tape Op #39)] and Eddie Van Halen used on “Right Now.”

How old were you when you did that recording?

I was ten.

Even at ten, you were getting ready for bigger and better things in the music business?

I thought that [audio engineering] was maybe what I wanted to do. I was pretty sure I was going to be in radio in some way,...