This is part 1 of a 2 part article, you can find the other part here: "A Practical Guide to Integrating Modular Synthesis in the Control Room"

It seems but a distant memory now, but yet somehow also like yesterday, when I first spoke at length with Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe [Tape Op #147]. Little did I know that it would prove to be a pivotal moment for me as an engineer. It was November 2015, and Deerhunter and Om were staying at the Michelberger Hotel in Berlin. We had a power sesh at the bar, and all stepped out for a smoke. I remember Deerhunter guitarist Lockett [Pundt], asking Robert how the shop was doing. I interrupted to ask, "What shop?" Lockett has excellent fashion sense, and I figured the answer was going to be about some new clothing shop in a weird part of Brooklyn. "Control," was Robert's answer. Still thinking the above was true, I asked more stupid questions. But as I listened to Robert explain modular synthesis and control voltage (CV), the sonic universe I had known forever began to show fissures on its edges and gradually dissolved into the limitless background over the coming months. I write a lot about dividing lines in one's journey as an engineer. This has proven to be the most profound and stark punctuation in my quest to document sound.

Within a month, I was at Control, a synthesizer shop in Brooklyn, picking up my first modular synthesizer rig. I asked Robert to help me put together something small to learn on, something that could also process audio. Shortly thereafter, I started bringing my synth to gigs, using both the processing side and a simple generative synth patch at FOH. During the course of some Deerhunter and Kurt Vile tours, the rig grew, along with my knowledge of CV. Eventually, I started tuning the PA with a patch instead of Black Sabbath's "War Pigs." I'd get up early on the bus for morning meditation-style patch jams on headphones in the back lounge, then later at the gig I'd be fading patches in here and there while Kurt switched between banjo or acoustic guitar.

This became the beginning of modular synthesis becoming part of my daily process as an engineer. It's why you're reading about this in Tape Op! I fully expected modular synthesis to be a more academic approach to sound. The surprise was the infinity pool of sonics it revealed. Learning about wave shapes, envelopes, and the difference between additive and subtractive synthesis helped me better understand non-synthetic sounds. Almost immediately, my mixes became less cluttered. I became able to visualize audio as never before. Sonic decisions and placement that previously took sleuthing and digging became second nature to me. I began to bake simpler and more delicious cakes. The density that is modular synthesis somehow shaped me into an engineer more conscious of space and restraint.

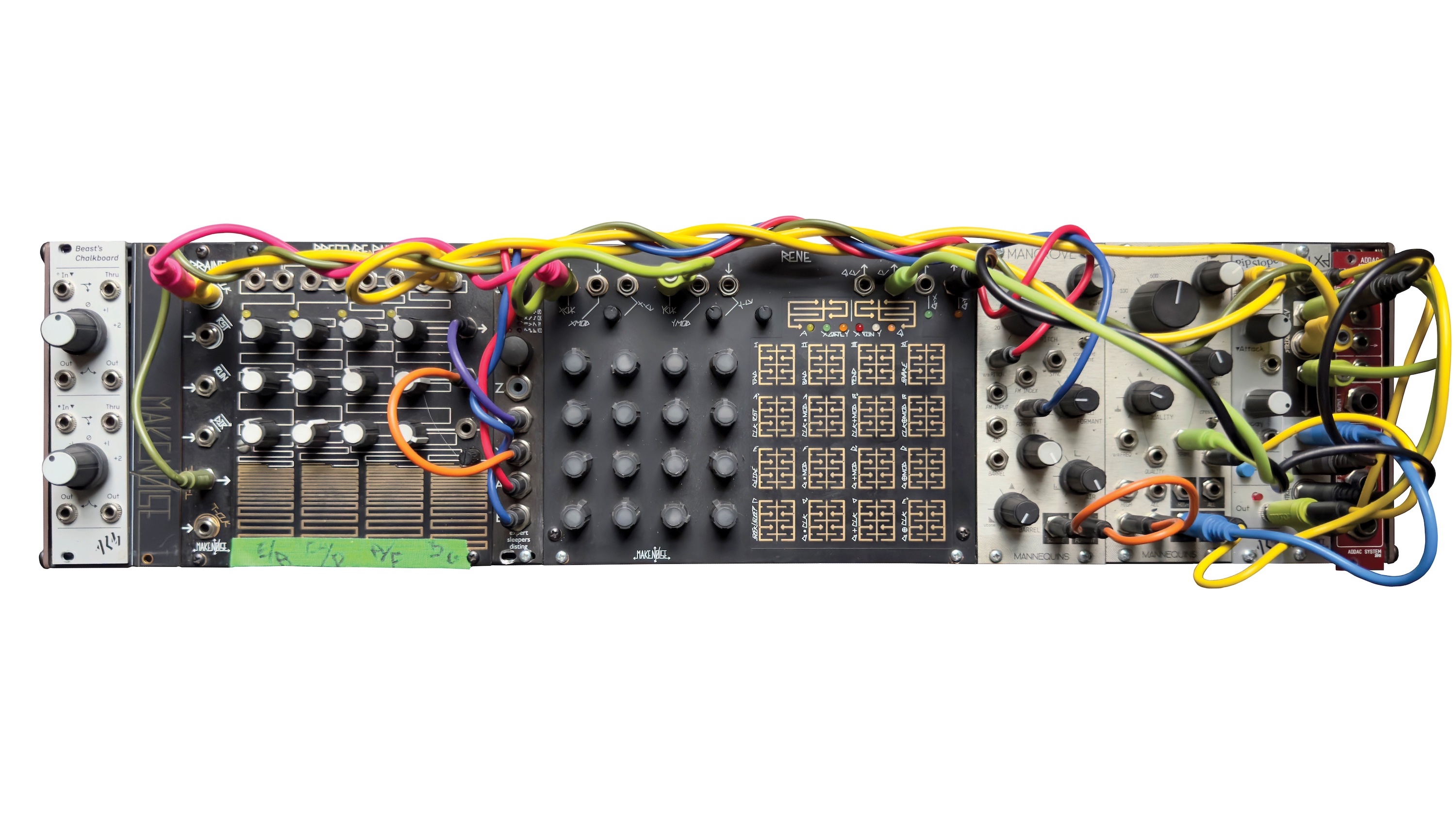

The rig Robert had designed for me slowly turned into the wall of modules you now see in almost every producer's IG feed. Like most esoteric gear that's visible in a studio, clients became curious and asked questions. I'd do my best to explain while dialing in drum sounds. The next question would always be, "Can we use that?" Of course we can! I'd plug an Arturia KeyStep or Korg SQ-1 in and build a custom synth sound.

After a few months of subbing patched-in modulars for traditional synths, I noticed listeners were immediately drawn to these parts of my recordings. Someone would ask, "What's that?" To be clear, these instances were almost always standard synth applications, but they were handmade, as opposed to the usual Moog or Korg sounds, and the folks asking range from my 72-year-old mom to synth heads like Black Milk.

Way back in the '90s, I started amassing gear that was decidedly uncommon. This was usually due to my budget, but I quickly noticed that sounds I'd get from and an old Supro or Ampeg combo would stand out from the usual Fender or Marshall fare at playback. This garnered interest from other engineers and bands alike. Additionally, it would translate to the casual listener, pulling interest where previously there was little or none. When the modular rig showed up, this now decades-old approach became geometrically effective. The synth as an instrument became another tool to set jams apart, and with the advent of a few utility modules I began using modules to process audio when mixing. Using MIDI or a kick or snare drum as a trigger, synced audio events as dramatic or subtle as called for became possible and much faster than drawing automation all over the place and using up CPU power.

This process has become second nature more quickly than I expected. From simple gated bass lines to complex events using envelopes and filters, to synced sample and hold voltage-controlled reverbs and delays or granular samplers, I found an extension of the above approach that is both limitless and totally controllable. I had thought the rig Robert designed would be mostly for academic-leaning Morton Subotnick "Silver Apples of the Moon" experiments [Tape Op #155] and maybe some mono synth here and there. This has been true, but more importantly an entire Z axis of sonics and effects has appeared. The result has been enthralling for me as a 52-year-old, doing this more than half my life. We all need inspiration, but more important is the effect on the casual listener.

Informed readers will note that I'm a huge fan of front loading both the creative and recording process, and the ability to do this using the modular world has been no different. To craft this type of processing environment quickly and have it on hand has been a boon to getting closer to finished-sounding work earlier on in the process. And it keeps both clients and the engineers at High Bias Recordings engaged and excited, as opposed to staring at a computer screen (or the back of someone's head who's staring at the screen).

The process of making decisions earlier and the excitement that ensues is priceless, but it's nothing new. In fact, it's as old as recording itself, like the razor blade Dave Davies used on his amp's speakers for The Kink's "You Really Got Me." The real payoff of modular in the control room is direct access to the listener's subconscious. The, "What's that?" moment I spoke of earlier is as old as humans and tied to actual survival. It's what happens when fourteen twigs snap under the weight of a foot behind you instead of the usual five, letting you know it's a bear and not your cousin. Our ears are drawn to these events, and the mind cannot ignore them until they're categorized and documented. In record making, this translates to engaged listeners who are fans already, but it also draws new listeners who are not. A fantastic, if not pedestrian, example of this would be the first time you heard "Song 2" by Blur or any Sun Ra record. You can't not listen. Accessing the, "What the fuck is that?" space in traditional record-making is invaluable, and modular synthesis has proven to be a treasure trove of endless riches in a growing horizonless sea of presets and algorithms. Having this degree of control and limitless sonic palate on hand has immeasurably changed my workflow and made for a surprisingly accessible new world of sounds. More importantly, it has availed a more unique creative statement for clients while also elevating the final result for the listener.

This is part 1 of a 2 part article, you can find the other part here: "A Practical Guide to Integrating Modular Synthesis in the Control Room"