Collections

INTERVIEWS AND ARTICLES BY TOPIC, CURATED FROM OUR ARCHIVES

The Drummer's Perspective

Dave Mattacks

Dave Mattacks is arguably one of the world's best drummers. His recording credits include: Joan Armatrading, Mary Chapin-Carpenter, Sandy Denny, Nick Drake, Brian Eno, George Harrison, Jethro Tull, Elton John, Paul McCartney, Jimmy Page, Fairport Convention, Paul Simon, Cat...

interview

Nate Smith: Listening Hard

BY GEOFF STANFIELD

A drummer can make or break a session, and I have always loved getting their perspectives on the recording process as well as the variety of roles they play in the studio. After several solo records and appearances on records by Dave Holland, Brittany Howard, The Fearless...

interview

Matt Chamberlain: Perfect Timing

BY GEOFF STANFIELD

Over the last 20 years Matt Chamberlain has contributed to a staggering variety of recordings including David Bowie, Tori Amos, Frank Ocean, Miranda Lambert, Bill Frisell, Brad Mehldau, Fiona Apple, and Edie Brickell & the New Bohemians, to name a few. Seriously, we're...

interview

Nick Mason: Behind the Scenes with Pink Floyd drummer

BY JEFF TOUZEAU

Nick Mason's recent autobiography, Inside Out, recalls his unique experiences as the drummer for Pink Floyd during for over three decades — he is the only member to have remained with Pink Floyd throughout the complete duration of the group's career. The book contains...

interview

Gary Young: Pavement's Drummer & Engineer

BY LARRY CRANE

Gary Young was the flamboyant original drummer for Pavement. He was also the engineer for all their recordings up through the Watery, Domestic CD. He still resides in Stockton, California, and runs his Louder Than You Think (16 track 1"analog/ Pro Tools system) studio out...

Recording Drums

The Synthesizer

BY JOHN BACCIGALUPPI

In 2005, Matt Warshaw, a well-known surf journalist who had written for just about every surfing publication that exists, published The Encyclopedia of Surfing, which became the definitive reference on the subject of wavesliding. With his new book, The Synthesizer, Mark Vail...

review gear

Hotkey Matrix 144-key controller for Pro Tools

BY ANDY HONG

The QWERTY keyboard that I use with my DAW is a fully-programmable Cherry SPOS G86-61410 (Tape Op #56) designed for use with Point of Sale register stations. Any keycode, key combination, or sequence of keys (up to 10 keycodes each) can be assigned to any of the hardware keys...

review gear

Isotools

BY DANA GUMBINER

ck when they were first introduced, I was skeptical of the Primacoustic Recoil Stabilizers monitor pads (Tape Op #62) that have since become something of an industry standard. Having little or no patience for what I then perceived as trendy gimmicks, it took the kindness of a...

interview

Reamping Drums

BY JOHN NOLL

Re-amping guitar tracks is a pretty common technique these days, but did you know you can also re-amplify drums? This process can solve problems and expand your sonic palette during mixing.

I was recently hired to mix an album that was tracked live in a club. The drums...

interview

Drum Tuning: Drum Tuning: The Studio Perspective

BY GARRETT HAINES

The adage "garbage in garbage out" takes on added meaning when it comes to recording drums. An out of tune drum can ruin any recording session. Unfortunately, very few people know the basics of drum tuning — including drummers! Many studio sessions involve drum heads...

More Collections

SEPTEMBER 28, 2020

Buyer's Guides

Welcome to Part Two of the Tape Op AES Buyer's Guide!

For the first time in maybe forever, the AES Show in NYC has been moved online due to COVID-19. It makes sense, but we're going to miss seeing all of our friends in person at the show.

Make sure to check out the online AES...

SEPTEMBER 14, 2020

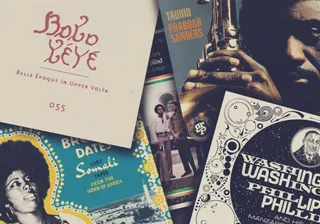

Dub!

Jamaican electronics whiz kid Hopeton Overton Brown got his moniker "Scientist" from none other than one of dub music production's founding fathers, King Tubby (Osbourne Ruddock). As a teenager he began engineering and mixing out of Tubby's, later moving to Channel...

OCTOBER 12, 2019

Jazz Recordists

A studio manager juggles responsibilities and must also find the time and space for creativity. It takes a level head and a scopic vision to stay sane and to be brilliant. Knitting Factory Recording Studio manager Sascha Van Oertzen runs her Studio with an ease that only comes from...

AUGUST 2, 2017

Women in Audio

With a start at New York City's Record Plant in the mid-'70s, Julie Last continued with her career at Ocean Way Studios in Los Angeles. Now living in Woodstock, NY, she runs her own Cold Brook Productions. Along the way she worked on sessions for Talking Heads, Cheap Trick...

JULY 11, 2017

Let's DIY

You've had the idea — the sound was in your head. You've said to yourself, "Self, I'd sure like to make this voice (guitar, drum kit, etc.) sound like it was recorded with a telephone. But how?" Well, you can futz around with filters, EQ and compression to...

FEBRUARY 14, 2017

All About Eno

Daniel Lanois' career reads like an enviable work of fantasy. From his early projects with Brian Eno and Harold Budd on their genre defining "ambient" recordings, to a pivotal role on U2 classics like The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree, and Achtung Baby, to his work...

JULY 12, 2016

Hip-Hop

Sometimes it's too bad Tape Op doesn't offer an audio version of the magazine. Whatever you might know or not know about Hank Shocklee, it's difficult without hearing him speak, to convey the abundance of energy, good humor and all-out love for music that wells up in...

OCTOBER 7, 2015

The Johns Family

Ethan Johns would be of note to the recording world if only for his familial ties. Being the son of Glyn Johns [Tape Op #109] and the nephew of Andy Johns [Tape Op #39], one might assume his entry into studio work was a shoe-in — but not so, as you'll see below. His current work...

AUGUST 31, 2015

Session Musicians

A drummer can make or break a session, and I have always loved getting their perspectives on the recording process as well as the variety of roles they play in the studio. After several solo records and appearances on records by Dave Holland, Brittany Howard, The Fearless Flyers, Chris...

JUNE 25, 2015

Programmers & Synthesists

It only makes sense that with a renewed interest in analog synthesis, modular synths would make a comeback. However, rather than the hulking beasts Keith Emerson tortured on stage, or pampered studio dwellers, like TONTO, the new Eurorack style systems are lightweight, portable and...

JUNE 25, 2015

Mastering

The least surprising thing about the 2017 release of the Giles Martin remixed version of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band is that its sonics – indeed, its very existence – was heavily and passionately debated. Audio engineers who work on historic recordings know they have to...

JUNE 25, 2015

Motown & Memphis

It is truly remarkable to step back and examine the full societal impact that some recording engineers and mixers have had on American culture. During his 18-year tenure as Chief Engineer for Motown Records, Russ Terrana captured and crafted the sounds for many of the Detroit...

JUNE 25, 2015

Heavy Music

Recording involves several processes — preproduction, tracking, mixing, and mastering. The methods involved in each step have changed greatly over time. Musicians, engineers, mixers, and producers have more choices than every before with regard to how they navigate through the recording...

JUNE 24, 2015

Artist/Recordists

Psych Pop has been enjoying a healthy resurgence. The loudest shots from the latest wave were fired by Tame Impala when they released Innerspeaker in 2010, soon becoming one of the biggest indie acts in the world. Whether due to interstellar grokking or flattering imitation, an army of...

JUNE 19, 2015

Behind the Gear

VintageWarmer was one of the first "must have" plug-ins for digital recording. Mateusz Wozniak is co-founder and lead developer of PSPaudioware. Recent plug-ins include PSP 2445 (inspired by the EMT 244 and 245 early digital reverberators) and the PSP E27 equalizer plug-in...