The history of recording music is half folklore. Tales of insinuation and glory have us turned around to the point where we don't know much about what really happened during most of the great recording sessions. Are those who don't know history doomed to repeat it? If only we were so lucky. We'd all like to make Sticky Fingers, we just can't seem to. True enough, most of us haven't had the band or the songs to get that kind of fierce air moving in a room in the first place. But let's say we did. What would all that sound become without the right person there to catch it, just so? Missed opportunity. Brilliance off-center. So how do we not miss these golden opportunities? Whom would we go to, to learn how to get music to stick to tape? Well, okay.

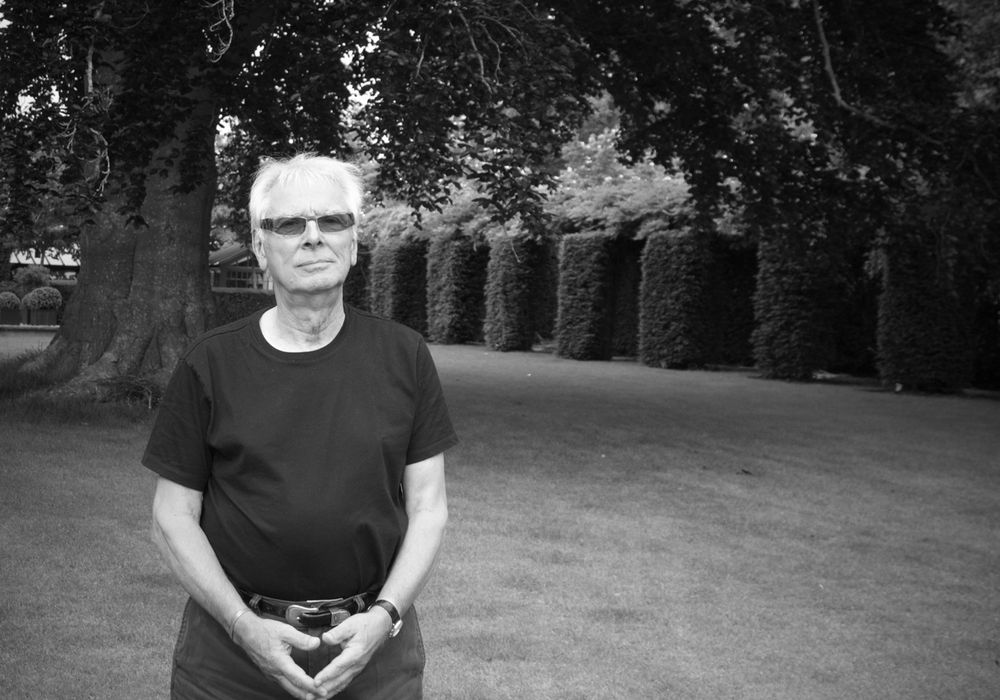

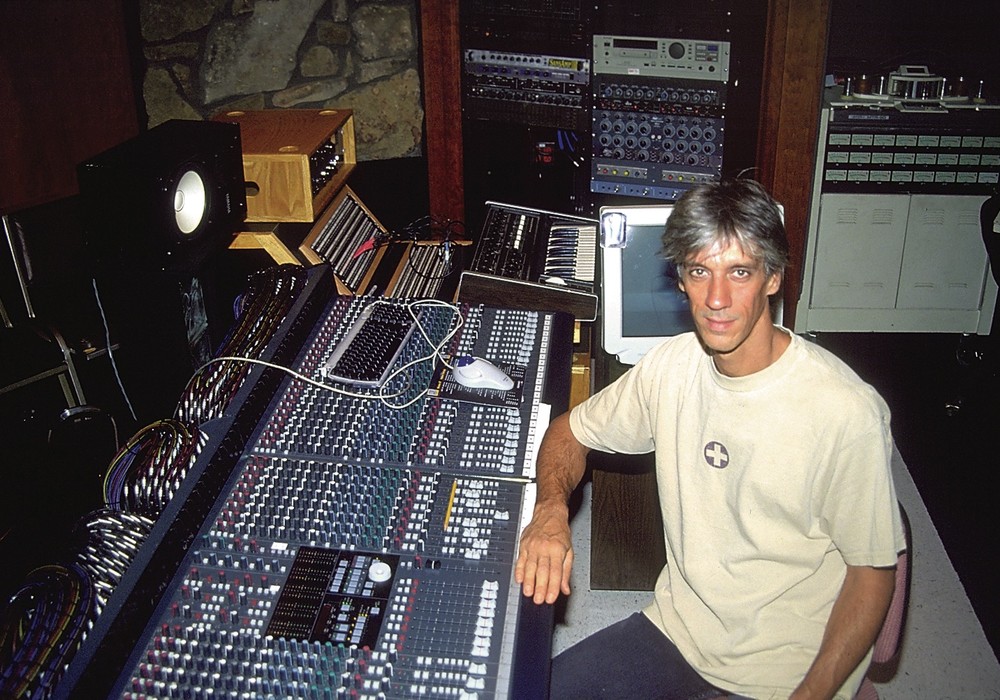

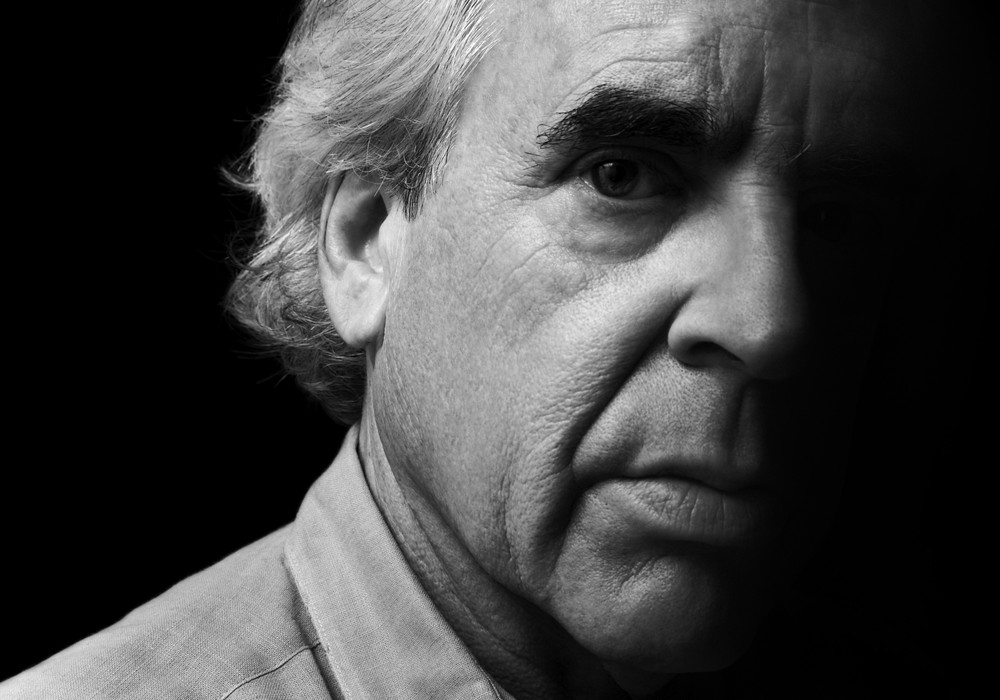

From the first minute you talk with him, Andy Johns is quite a charmer. After five minutes, it's readily apparent why anyone from the Rolling Stones to Led Zeppelin would want Andy along for the session: He's a rare marriage of intelligence, quick wit and knowledge, with the even rarer quality of seeming non-hierarchical in his attitudes. Since he doesn't pull any punches, it's easy to see why you'd trust Andy in a critical situation. How lucky then that he's also a brilliant engineer. While he probably wouldn't like this terminology, let's face it: Andy Johns is a legend. He's recorded many of the records that modeled rock 'n' roll. "When the Levee Breaks", "Bitch", "Marquee Moon" and an array of other tracks containing some of the sounds that are touchstones for a whole generation of sound-recordists. And he did a lot of it while he was in his twenties. In spite of his prodigious output, it's quite possible Andy will never get his due. His older brother Glyn is also a legendary figure who cast a shadow over Andy in the public's eye early on. This abundance of family talent, a history of less-than-explicit album credits and eclectic producing jobs have made the Andy Johns saga an enigmatic one.

I woke Andy up in the middle of the afternoon with a "bit of a cold". While he said he was feeling not "quite chipper", he then talked affably with me for a couple of hours. He was candid, to say the least, but never with the touch of malice that you often find in people who have been doing it for over 30 years. As the past fades, it might be impossible for any one of us to sort through all the lore. Everyone writes their own biography sometimes fashioned more for entertainment than history. Andy can't help being entertaining, but he knows his craft, and, in his own way, tries to set the records straight.

You started off as a tape op at Olympic?

Yes, in 1967. My brother, Glyn, who was, like, the first freelance engineer in England, ended up doing a lot of work at Olympic and got me an interview there. I was lucky to start off at Olympic because it was extremely popular with rock 'n' roll bands. In the course of a week there would be sessions with Joe Cocker, Jimi Hendrix, Manfred Mann, Mick Jagger producing something. At the same time during the day there would be orchestral sessions because they did a lot of movie soundtracks. I learned a lot from that, too.

Did you move quickly to engineering?

Yes. Now it's awful. I see guys now — they're janitors, then they're assistant engineers after a year or something and then they can stay doing that forever and ever and ever. Back when I started it was, "Hello", sit in on a session and then in two days they were putting you on dates. There wasn't as much to know back then and the engineer did a lot of the patching and stuff, where nowadays assistant engineers really do everything, which is fine with me! So, as soon as they saw you could get away with it, they'd put you on sessions as an engineer. Back then when new clients called up they wouldn't ask for a specific engineer, they'd just book time. They would show up and you would say, "Hello my name is __ and I'm your engineer," and they were none the wiser. Then, if you impressed them they would ask for you again. So, because the competition wasn't very strong back then, within a year of me starting to do engineer sessions I had a pretty solid clientele. I had already done some pretty big bands — Blind Faith and Humble Pie — so I was able to go out on my own and make a little bit of money, which was great at 19 years old — to have some cash. At 19 you don't have any responsibilities, but then I spent 360 days of the year in the studio!

So you didn't have much social life...

The only people I met were people at the studio. In fact, my first wife, I married her because she was about the only girl I saw for two years! She was the receptionist at a studio, so that's how glamorous it all was!

It's funny you say that, because one could credit you and your brother for making engineering a glamour profession!

Well, let's not forget Uncle Eddie Kramer as well! He made sure that he was noted. When I came along they had just started putting the engineer's name on album covers. Because, as much as anything, of Sgt. Pepper's... The general public realized there was a lot of hocus-pocus that went on in the studio and it kind of validated that part of the profession, and you got your name on the record and you didn't have to ask. But I used to like to get my picture on, too, if possible. That's how awful I was back then!

Did you meet Eddie Kramer at Olympic?

Eddie Kramer sort of trained me on the Axis: Bold as Love sessions. And he was somewhat of a taskmaster. But I learned a lot from him. Eddie is very clever.

Now, did you work on Physical Graffiti together?

Well, no.

You're both in the credits...

The reason I'm on there is probably the reason Eddie is too. They [Led Zeppelin] were working with Ron Nevison at this point. I'd had my falling out with them but there was stuff left over from previous sessions. There were two or three tracks that were credited to me as engineer but they were probably from the third or fourth album. Maybe they did work with Eddie in New York.

I heard a rumor you did a mix of Tommy at the age of 19.

No, I'd been actually engineering things for about three months and I hadn't got a clue. Kit Lambert shows up wanting me to mix "Pinball Wizard". I put the tape up and it...