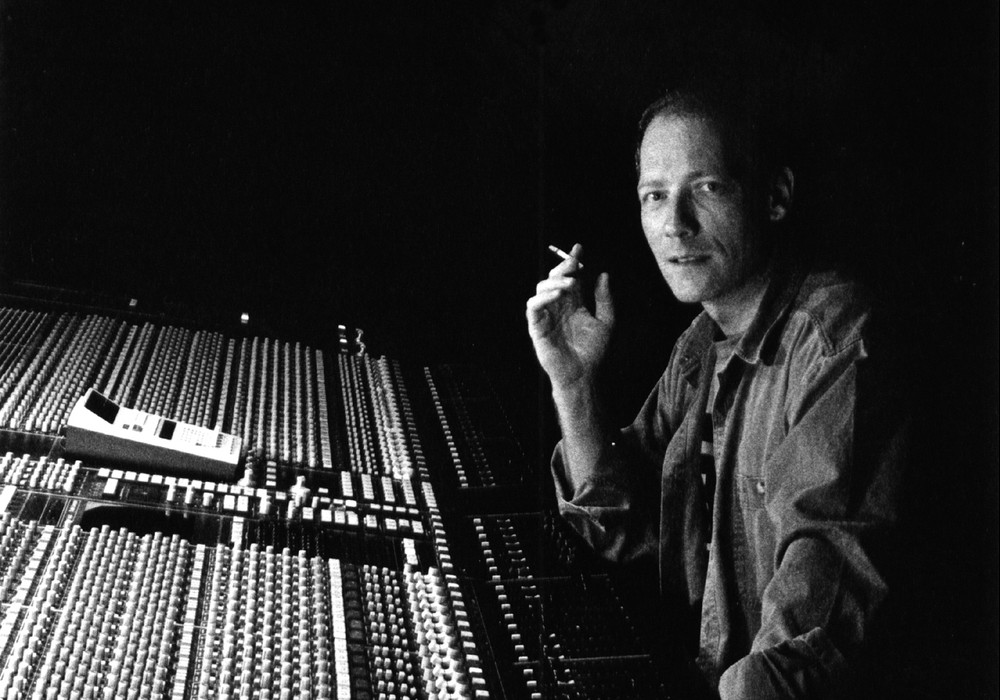

On a beautiful day in early March, Oz Fritz showed up at the door of New, Improved Recording — a studio I co-own in Oakland, California. He had been hired by multi- instrumentalist/singer Mark Growden to co- produce and engineer Mark's new record Saint Judas. I was pretty nervous. This was the guy that recorded and mixed Tom Waits' Mule Variations, Blood Money and Alice, worked with Bill Laswell over two decades, and has worked with Wanda Jackson, Iggy Pop and the Ramones. The man that showed up on my doorstep that day surprised me — Oz Fritz is as unassuming as they come despite all the great things he has accomplished, and I was immediately at ease talking with him and helping him get set up. He walked into the control room with only his trusty Peavey Kosmos Pro and a very practical attitude towards the task at hand, which was to capture the sound of Mark's sextet performing their songs live. Luckily he had time to sit down with me one morning for breakfast to talk about Meat Loaf live albums, quantum physics, magical battles and recording music that can't be recorded.

Tell me about starting out. Did you go to recording school?

I did go to recording school. I'll give you a real brief synopsis of my history — I got really interested in manipulating audio when I was eleven years old. My friend and I recorded "Revolution 9" from the [Beatles'] White Album onto a cassette tape, which were fairly new in 1969, and then we took it apart and flipped it around so we could hear it play backwards. It was an incredibly spooky experience. After high school I started doing live sound. I did that for four years in the Western Canadian bar band circuit and got to the top of where I could go. I went to New York on a visit and really loved it there, so I tried to find a reason to go back. I discovered the Institute of Audio Research, and I went there for a year, in 1983. I went back to Canada, couldn't find work in studios there, went back to New York two years later and started out as an intern at a studio called Platinum Island, that was an up-and-coming, state-of-the-art studio that eventually rivaled The Power Station, which was the studio of the time. Then, after a couple of years working there as a staff engineer, Bill Laswell came in — he was looking for an alternative to the Power Station, where he normally worked. We hit it off and when I went freelance not long after, my first few years were as his full-time engineer at his Greenpoint Studios that he opened up in Greenpoint [Brooklyn].

That was the late '80s?

I started as an intern in 1987, went with Bill Laswell in 1989 and went freelance in '89-'90.

From your school experience through being an intern, an assistant and finally a staff engineer, was there a particular methodology that you feel you learned?

Well, there's a pedigree. The great thing about working at a commercial New York studio is that you work with all kinds of well-known producers and engineers in different types of music. I sort of aligned myself mostly with the people from The Power Station. My main engineer-teacher was Jason Corsaro, and his pedigree was The Power Station and Bob Clearmountain. I learned how to get big drum room sounds from Jason and Tom Edmonds, who started out working with Todd Rundgren up in Woodstock. Roger Moutenot [issue #20] passed on the lineage of another top New York studio called Skyline. I learned a great technique from Roger when he recorded Caetano Veloso singing and playing acoustic guitar. He placed a [Neumann] FET 47 at about the level of his chin angled toward his mouth. The rejection side of its pick-up pattern was facing the guitar to minimize guitar bleed. Some months later I used the same technique for recording the Turkish saz player, Talip Özkan. His album, The Dark Fire, was an early successful recording for me. I learned how they did things at the Hit Factory from Robert Musso and Bruce Tergesen. But back to Jason Corsaro — when I did live sound, it was predictable that every drummer would come up and tell you, "I want my drums to sound like John Bonham, Led Zeppelin," except at one point a drummer came up to me and said, "I want my drums to sound like the drums from Power Station," and it was my friend Jason who came up with that sound. It was such an incredible sound that when John Bonham died one of the drummers they were thinking of getting was the drummer in Power Station — they tried him out and he wasn't that great. Because it wasn't his playing that was so awesome — it was the sound that Jason got.

You're talking about Robert Palmer's band, Power Station?

Yeah. They were called Power Station because they worked at the studio a lot.

You're saying that sound was more tied to the engineer than to the studio — if he worked somewhere else he'd get a similar sound?

He...