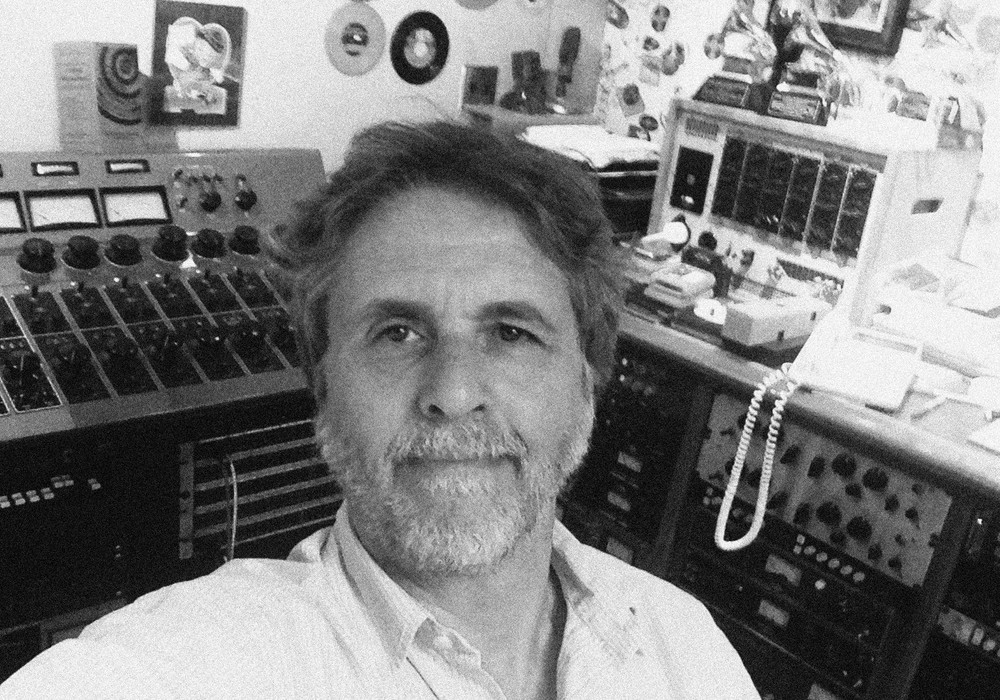

We first interviewed Mark Linett in Tape Op #47 about his work with Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys. Since then he’s overseen an extensive amount of The Beach Boys’ archives, and with the recent release of Feel Flows: The Sunflower & Surf's Up Sessions 1969–1971, I dropped Mark a line to see how projects such as these get done. We also got the chance to talk about his mobile recording work. Check out this interview on the Tape Op Podcast as well!

You’ve done a fair amount of these Beach Boys box sets now.

A ton of them. My first CD was Pet Sounds [remastering], all the Capitol era albums, and the bonus tracks, the ‘93 Good Vibrations box, and The Pet Sounds Sessions.

That’s a good starting point. That Good Vibrations: Thirty Years of The Beach Boys box set was kind of my introduction into what extra tracks were out there.

Yeah. The one that we did in 2013, Made in California, that’s even more extensive and up-to-date, just in terms of the mastering. It didn’t get quite as much attention. The difference between the record-buying public in 1993 and 2012 was quite large. I have a gold record for selling 125,000 copies of the Good Vibrations box. You bought it or you didn’t back then. In ‘93 we couldn’t even steal it online.

Yeah. That was a totally different era.

Totally different world. This new one’s a big success having sold out its initial run of, I think, 10,000 physical units, which is exceptional these days.

How do the economics of this work?

Whenever we do a project, we tell them what we’re proposing – as far as how big it is, and then how much it’ll cost. It’s all price-fixed. There’s no more “just do it and bill for it until it’s done” kind of projects, on probably any level. They somehow run some algorithm that says, “Yes, we think we can sell X, and so we’ll allow you to do Y.” In this case, it’s exceeded what they expected, so I guess the guardrails will be somewhat wider next time. It’s all beyond me. I miss the good old days, when, on any project, not just this one, it was pretty much, “Do it until the money runs out.” I worked on so many projects back in the day that seemed to have endless budgets. Of course, they would never recoup.

With the instigation of something like Feel Flows, are you and archivist Alan Boyd discussing what’s in the vaults?

Oh, yeah. The main advantage we have is that for 20 years now, we’ve been transferring and archiving everything to high-res digital. Up to this point, we pretty much had everything already on file and from that we had a pretty good idea of what we had to work with. There’re maybe 20 or 30 tapes for the next period that I need to pull and transfer. We’ve transferred about 90 percent of the Beach Boys’ holdings, which are very extensive.

I find it amazing that items weren’t lost in the archive, or not archived.

Yeah, some were. Actually, of their major recordings, there’re a handful of things that we don’t have and never found. We don’t really know what happened. We could guess at a few cases. There are some that have come back to us over the years, either under somebody’s bed, or tapes that were borrowed by persons known and unknown. I personally paid for a huge pile of stuff that was being offered to us by some kid ten years ago. Clearly, he wasn’t the one who got them. I wound up paying for them and sitting on them, and I was finally able to get someone to pay me back. But if I hadn’t bought them, they would have gone who knows where.

Right.

There’s a studio out here called Valentine [Recording Studios, Tape Op #116]. It’s actually back in business now. The Beach Boys recorded in it in ‘68. They did some of 20/20 there, the song “Break Away.” Around 10 or 15 years ago, an engineer friend of mine called me up. I had called them – as I called every studio in town I knew they’d ever worked at one point, looking for material – and asked. He said, “No, we don’t have anything.” This was when they were still in business. When the owner died, they basically locked the door and left it. His kids owned the building and were running another business next door [Metropolitan Pit Stop].

With the little cars!

Oh, you’ve been there?

Yeah, I’ve been to the studio.

Somebody got in the studio and said, “Hey, I was in the tape vault, and there’s a Beach Boys tape.” I got ahold of the then-owner, which was the daughter, and I got to see the 1-inch tape, but they wouldn’t let me have it because they weren’t studio people. It took me eight years to get it back. It wasn’t until Nic Jodoin, the producer who’s been running the place, took over and told them, “No, no, no.” I finally got it back after eight years. It was the 1-inch, 8-track master for a song called "All I Want to Do," which is on 20/20. It was three different reductions from a previous 8-track, with three different lead vocals. Two by Dennis [Wilson], one by Mike [Love], the Mike one being the one that’s on the album. But it took eight years to get it back.

When you come across reduction mixes, are you always able to synchronize them back up with the previous tape? You obviously did so for Pet Sounds.

Oh yeah, sure. I do it all the time. I was actually looking at something over the weekend and debating whether to or not; I probably will try to sync it up. I’ve gotta see what’s been added, because sometimes parts get added as the reduction is made, as part of the reduction, and that can be an issue. Not terribly often, but in this period. Until they got to 16-track they were still doing 1-inch, 8-track. And then Steve Desper would mix the track down to two or maybe four tracks on the next 8-track, leaving 4 tracks or 6 tracks for vocals. We have a number of songs like that on this set. Going forward it’s all 16-track.

Yeah. That starts to make it an easier transition, in certain ways.

Yeah, it’s one less thing to do. I’m going to miss the fact that Desper isn’t engineering anymore, because his work was so good. When you pull the tapes up, it’s a real revelation. Not a surprising one.

I assume you’re sourcing the original master mixes on a lot of this for the albums?

Yeah. We reissued the two original albums. This project has been very convoluted, for a lot of reasons. We were talking at one point about doing a remix, and some of the fans were disappointed that we didn’t do a remix. But then if we had done it, there would be fans who would be annoyed that we’d done a remix. I personally felt like, given the number of formats, we have a five CD box, a two CD box, and vinyl, 4 LP vinyl and 2 LP, that maybe we should have done it. It was never really seriously discussed, however. Possibly from a cost basis. It seems to me that unless you’re The Beatles, you don’t get away with that.

To be able to hear an album in a different light can be really fascinating, to understand how the music was built.

Just to hear it. I remember when I started with this organization in ’87, working on Brian’s first solo record. I don’t remember why, but, at some point, we rented an Otari machine. It was a 1-inch 8-track, or a machine that had 1-inch heads. They sent over the 1-inch Pet Sounds master, which had about half the album on it, with the track in mono and the rest of the tracks, some of them anyway, being vocals. I just remember being able to push up the faders and hear that. At that point I was completely unaware how it had started. The tracking date was done on three tracks of a 4-track and bounced down to mono. But yeah, I love hearing that. I wish I could have made records back then. It was a lot more exciting than the layer cake approach. By the time I got into the studio, it was 16-track already. We were heavily into building it in pieces. There’s nothing wrong with that, but there are few things I’ve done, even if they’d been done multitrack in the digital age, where you’ve got everything out on the floor. I did a soundtrack for a cast album years ago in New York, with a full pit orchestra, and the singers in booths. A cast album is very expensive, because they get paid a considerable amount for every day that they’re recording a soundtrack album. You pretty much have to get it right on the spot. You don’t do endless vocal overdub sessions. Of course, they’ve been doing eight shows a week. It’s not a heavy lift for them to do that. But to do something that way, with everything laid out and coming at you. I once asked [engineer] Chuck Britz, who did all of the early Beach Boys records – all the big hits – why he stopped. When I met him in 1993, he was working in the tape copy room at Hanna-Barbera. A wasted talent. I asked him why he stopped making records at a fairly young age. His answer was, “Mark, I couldn’t stand all that overdubbing.” I can understand that! Those vocal sessions must have been hard enough, because that took lots and lots of time. To go from the excitement of cutting the “God Only Knows” backing track in one long four or five hour session and never changing a note, to, “Oh yeah, let’s sit around all day and do voice overdubs and isolate everything.” That must have been tough for an engineer. I’m sure he was on salary, but I’m sure he booked overtime at some point.

With the archive work, when do you make a call whether to do a new mix?

Well, this album was kind of interesting in that there were some original mixes that we didn’t use. But, frankly, sonically they weren’t terribly great.

Just odd balances?

There are a few things on here that never made it to CD before, so we specifically included that. I suppose, to a certain extent, it’s a kind of vanity that you want to do it as opposed to just leaving it. Like I said about remixing the albums, I’ve never really heard anybody else’s remixes that I thought were better. Maybe that’s just me, but I never really found The Beatles remixes… It’s like, they remixed Abbey Road? Why? Remix Who's Next? Why? If it’s only as an alternate way of looking at it, it’s fine. That was our big thing when we did Pet Sounds in stereo, to make a big point that it’s not meant to replace it. It’s just an alternate way of listening to it. It specifically wasn’t ever meant to be released on its own, which, of course, lasted about a minute. What worries me about remixes is that since everything is online and streaming, if you go and listen to something, which version are you going to get? If that’s what’s being exposed to a new listener, as opposed to what the artist originally approved and intended, then it gets a little dicey. I would never want to do it and have it replace the original.

What’s the next Beach Boys era? Holland?

It hasn’t been set in stone yet, but I think it’s going to happen. We’re going to do Carl and the Passions, Holland, and we also have their concerts from Carnegie Hall in 1972 and another one the day before in Passaic, New Jersey. Those all have to be released in some form. The other thing that’s been driving a lot of this is this weird copyright law in the U.K. When it was last modified, it said that what hasn’t been commercially released within 50 years of its creation – not released, but creation – if it wasn’t released within 50 years and it does come out, it’s public domain. It’s why you see these Dylan bootlegs. The problem with The Beach Boys, is that somewhere in the early ‘80s their stuff got heavily bootlegged. We’ve been dealing with that, because if it’s already out there as a bootleg and we don’t release it legitimately, then the anybody can own the bootlegs. Let’s release it legitimately in some form to retain ownership. It’s kind of been a boon for the fans. The project we did in 2018 for the Friends and 20/20 albums [Wake the World: The Friends Sessions, I Can Hear Music: The 20/20 Sessions], which unfortunately not was not a physical release, wouldn’t have happened at all if it weren’t for the copyright. We did all the usual things; tracks, mixes, but there was a lot on there that was unreleased, including half a dozen live shows. If it weren’t for that copyright law, we probably wouldn’t have been able to do those projects. That’s the wonderful thing about The Beach Boys controlling their tapes and not turning them into Capitol all of those years. If they had turned in all the Pet Sounds takes we have, Capitol would have kept maybe the last three or four tracks, or the eight tracks, and that’s it. They would have thrown out the sessions. I don’t blame them; you can imagine they’d need a warehouse the size of Rhode Island by now.

You’ve focused on the live recording aspect recently.

Ten years ago I basically put my focus on live recording for broadcast. I work for iHeartRadio, among others. Tomorrow will be our sixth show this year. We’ll be doing Coldplay tomorrow. When I get done with you, and I’ve gotta go over there and get my COVID test.

You never thought you’d be doing that just to do a job!

No. You think about all kinds of things, but a pandemic that’s going to shut down the world and everything you do was not at the top of my list for worry.

Describe your mobile truck and everything for us.

Yeah, we built this mobile truck 11 years ago. It’s actually the same as what we have at iHeart, based around a Digidesign D-Control as the mixing surface. Using a static Pro Tools system with plug-ins as the mixer, which is great because if you go out live and just capture it, you can pick it up on a drive and take it home and pick up right where you left off. That’s what this truck originally had. I think we were probably running 80 inputs, or something, max. Then, about five years ago, there were worries about the reliability of using the Pro Tools surface that way. There’s no redundancy and Pro Tools can be quirky.

I’ve noticed.

We got rid of those and bought Lawo digital consoles. They sound great. I’ve still gotta mix in Pro Tools, so we’re going to start over if I do that.

How many inputs are you currently running on your mobile truck?

It depends. The truck can do 192, and that doesn’t happen anyway. You get close to that at the Grammy Awards because they’ve got two stages and all that. For iHeart we can do 80. About 12 of those are taken up with audience mics and production. We’ve got hosts and media playback. Coldplay’s way more than that, but they have a real good stem mix setup. We’ll be dealing somewhere in the neighborhood of 40, plus production. It’s funny to put up a 16-track or a 24-track tape and just go, “Oh, this is nothing. This is nothing!”