What do Bob Dylan, Lucinda Williams, LL Cool J, Ozzy Osbourne, Tom Petty, Johnny Cash, U2, Mick Jagger, AC/DC, The Damned, The Posies, and Rage Against the Machine all have in common?

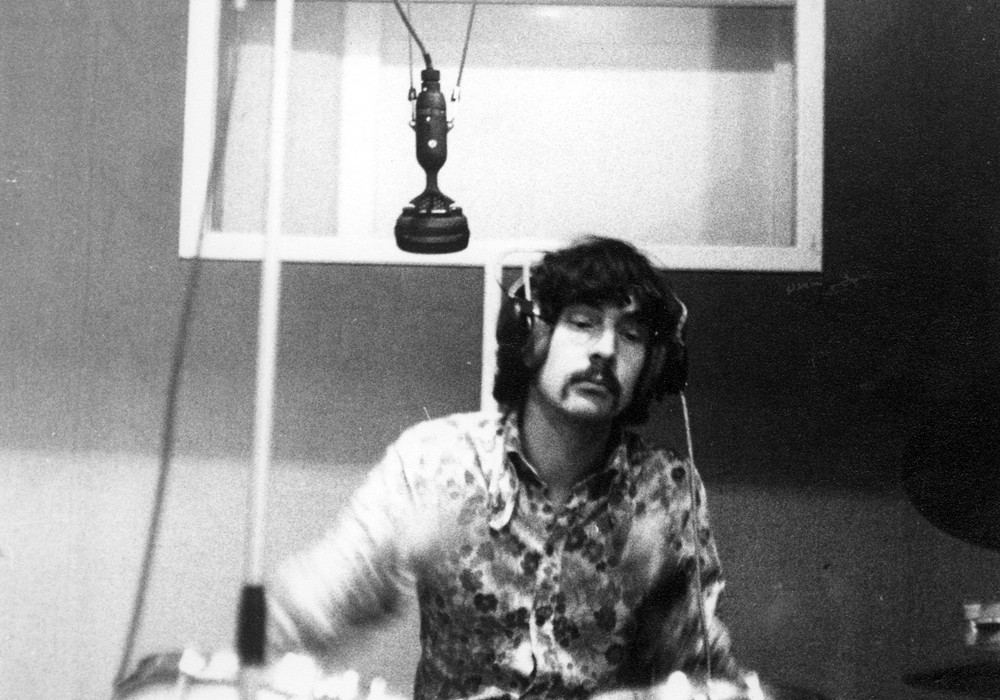

They all belong to a long and diverse list of artists that have had David Bianco touch their music. I fondly remember my own daily ritual of going into Toast Recording in San Francisco, in 1997, to work on my band's (Black Lab) debut record for Geffen/DGC. David and I have been friends ever since. I recently caught up with him at his studio, Dave's Room.

What was your path to L.A.'s Record Plant Recording Studio?

I played in bands all through high school and college. I moved out of my parent's house after I graduated college. I had a communications degree and I decided, "Well, I'll be a big time cameraman" or something like that. My girlfriend had cracked up my car, and I lived within walking distance of Record Plant. David L. Wolper Productions was across the street, at the time. I had my last résumé, after months of not finding anything and realizing that the union had a lock on any camera work. I walked into Wolper Productions and the lady at the reception desk said, "I'm sorry sir. We're closing." I walked outside and there was a wire trash basket, which I threw my resumé in. As I did that, I looked up and there were the big ol' psychedelic Peter Max letters, "Record Plant." So I fished my résumé out of the trash and walked across the street. I met Rose Mann, handed my résumé to her, and she gave me a tour. I didn't know anything about recording studios. My bands did home recordings, but we'd never been in a big recording studio. They had Dave Mason [Traffic] in one room, Crosby, Stills & Nash in the other. Stevie Wonder had finished up Talking Book in Studio B, and The Eagles were in Studio A. I was like, "Yeah! This is my kind of thing!" I walked down there every day and hung out, until management said, "Why don't you give him a broom if he's going to just stand there?" I had taken a job at a Pier One Imports as a cashier; then I got a call from Rose saying they had an opening and she asked if I wanted to come down. I said, "Oh, I have to give at least a week's notice." When I told her where I was working, she laughed for about a half hour on the telephone. She said, "You know, I like that you would do that, jeopardizing this job for that one." I started answering phones at night and on the weekends. Then I worked my way to janitor. They started giving us free reign to work in the studios on the off hours to learn. I recorded every weird hair band in L.A. in the late '70s and early '80s for free. That was the beginning of the Red Hot Chili Peppers and The Knack. They'd all say, "You're going to do our record, man," and then you'd never hear from them again. [laughs] But I learned, worked, and lived there. I'd be there 86 to 90 hours a week, sometimes sleeping in the back. That's how I learned how to record, and I worked my way up from there.

Some of your early days at Record Plant were spent doing mobile recordings.

I started answering phones, then I got a promotion to janitor — I actually got to be in the studio because I was cleaning it! Eventually I was an assistant engineer, and the remote division of Record Plant needed somebody. I developed it, side by side. I would assist in the studio when I wasn't doing a remote, and vice versa. I did remotes for about five years or so, and got my first "big break" recording Nazareth live — their engineer couldn't make it back from England. From there I got more and more gigs as a first engineer doing remotes.

What were some of the other artists you did remotes for?

We used to do a regular gig at The Roxy. You never knew who was showing up. It'd be Aretha Franklin, Van Morrison, The Psychedelic Furs, or David + David. We also went on the road with Bruce Springsteen, Joni Mitchell, and Arlo Guthrie. We probably rolled more tape on Springsteen than anybody.

Has any of the Springsteen tape ever seen the light of day?

He finally released that three CD/LP set [Live 1975-85].

What was your first break, outside of mobile engineering gigs?

My demos were getting around the place, and people were starting to hear what I was doing. Rose recommended...