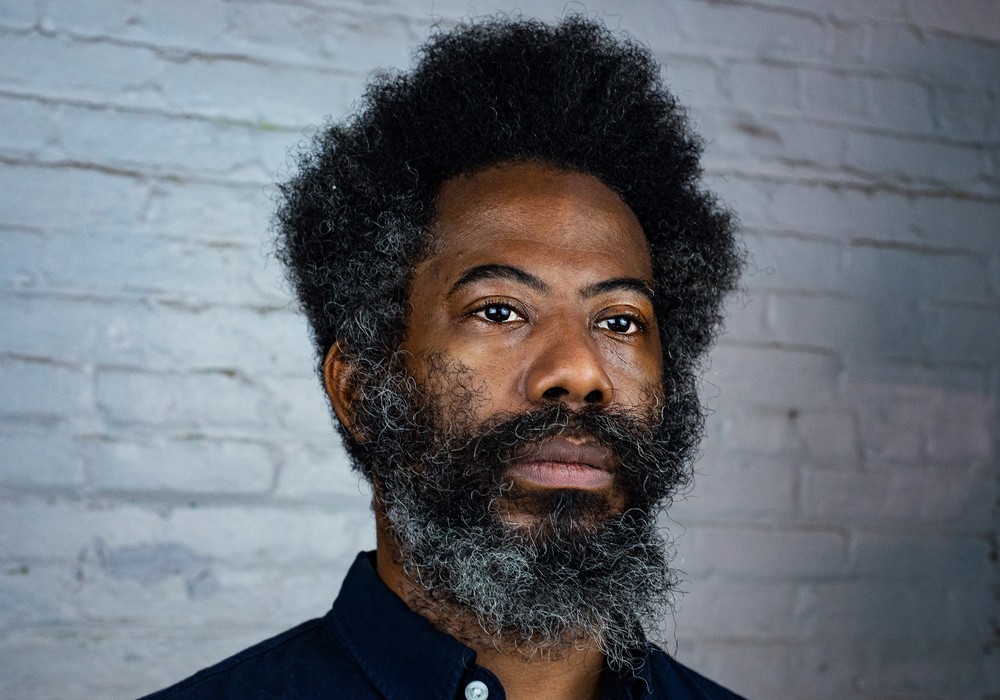

What began as the solo project of front man Will Toledo, Car Seat Headrest initially released a series of lo-fi and experimental albums on Bandcamp. The band's name is a reference to Toledo's necessity of recording vocals in his car while still living at his parents’ home at the time. In 2015 Car Seat Headrest signed to Matador Records, and recently released Making a Door Less Open, a stylistically divergent record containing elements of hip-hop, EDM and even doo wop. I caught up with Will to chat about self-producing and a tour-less summer.

-LC

How you doing, man?

Not bad. Yeah, this morning I was making an edit for “There Must Be More Than Blood.” I just got word that maybe that’s going to be the next single for radio.

Are you shortening it down?

I had to shorten it down a lot, yeah! Me and Andrew [Katz, drums] were talking about that, because it felt like a really good track. Matador wasn’t thinking about it at the time, but I think some DJ said, “Hey, it could be good,” so they changed their mind, and now they’re asking for it.

Is that kind of hard, taking a song that you’ve spent a fair amount of time getting to where you like it there for the album obviously, and then trying to excise parts of it just to get the length down?

Yeah, it was. Especially going into Teens of Denial, it was really difficult. We actually rewrote some of those songs to try and get them to the 3:30 mark. I kind of found out the hard way that that’s not what anyone wants. They want the exact same as the album version, but somehow twice as short. Putting in the extra effort to rewrite it is not really worth it. You just kind of have to have it in the back of your head if you’re making a longer track to have a plan B, if it does need to be that short.

Just maybe kind of visualize excising certain sections almost?

Yeah. This one was relatively easy, because it’s pretty flat. It just has section after section and this long, guitar solo intro. I just cut that out. And the middle section, and that’s already two minutes gone. Then it was just kind of trimming from there.

A lot of the songs on the new record are like big exposition or catharsis. If you say here’s the bulk of the song in the center, I feel like sometimes, or on the record you did with Steve Fisk [Teens of Denial] has the kind of beep-y loop sound and builds up…“Vincent,” is that right?

Oh yeah.

Then it turns into something. A lot of times there’s a big kind of catharsis at the end. But then you’re like, “How do you not have those parts?”

Yeah. That’s something that I always wonder. Especially if radio chooses a longer song, I think what you want is that build. But how are you going to get it in that condensed format? Actually I got really mad once, because “Drunk Drivers/Killer Whales,” we did a rewrite of that and spent all this time getting it down to three and a half minutes. We did that because Matador had sent us this edit that they did which was just incomprehensible to me, just like half of a verse, then the chorus, then the bridge. Then I found out like half a year later that’s what they ended up putting out. They didn’t even bother promoting our rewrite.

When you rewrote it, did you just end up changing the structure and re-recording the whole song from scratch?

Yeah, pretty much all we kept in was the bridge, which is sort of the hook of the song. But the verse and chorus was very much abbreviated. It became a very different-feeling song, which in retrospect, I can understand why you wouldn’t want to part with the original, because it did end up so different. But actually after we rewrote it, the band was like, “I wish we could just play this version. It’s a lot simpler and more straightforward and kind of more fun to play.” The set up with a long song is that you just really have to commit to playing it when it’s on the set. If your biggest song ends up being a long one, you better be prepared to commit to that every night.

You’ve got a few. Obviously every album’s got a couple of tracks that stretch out more. My friend used to say, “Play the longest song on any album, because that’s what they really want to be doing.” Is that the case for you?

[laughs] Um, like whether I prefer long songs on the record?

If you think of it like, “Oh, there’s no commercial potential, and this is where I’m going to just stretch out and do what I really feel like doing,” as opposed to trying to present something that’s digestible.

Yeah. It’s definitely just kind of getting into a different mode. I used to just write without any sort of consideration for either commercial appeal or playing live. I think that the practice of going on tour is really what’s changed how I write the most, because if you’re just laying it down for a record, then you can get it perfect once and not have to worry about it anymore. But if you’re laying it down and also you maybe want to play it live, you want to have that option, then you also have to make it in a way where you can sort of change it. You can be flexible with it. If you can’t be flexible with a song at all, if it only really works in this one way, then it’s not any fun to do live, because you just have to stick to that grid.

You’ve gotta be very rigid.

Yeah, you’ve gotta be rigid. So it’s just kind of a song-by-song thing. That’s one reason why our latest record had shorter songs overall, but even the longer stuff, it’s longer in a sort of jammy way, where it’s flexible and you can shrink it a little or extend it depending on what the mood is.

Yeah. Did you first start doing a band after the Matador signing, like putting together a band to really play out after being signed?

We lucked out where it happened at the same time. I moved to Seattle in 2014, and I was looking for a band. I had a set of demos that ended up being Teens of Denial. I was looking for a band to play with. I wasn’t really looking for a label. I was hoping that would happen at some point, but I had no idea how to look for one. I was focusing on getting a band, getting a live show together, and so by the end of 2014, I was working with Andrew, his friend Jacob [Bloom] was on bass, and we had sort of a three-piece going. Right around then, we put out an EP called How to Leave Town, which was just kind of extra material from the Teens of Denial stage. I was writing a lot of stuff, and How to Leave Town kind of became stuff that didn’t fit on Teens of Denial. That ended up attracting Matador. They got in contact and said, “What are you up to? What are your plans?” Luckily, we had the band, and we were able to invite them out to a show, so everything kind of took off at the same time.

How did they find out about you? You had records out on Bandcamp. You were self-recording and self-releasing.

Yeah. It was sort of a slow-growing thing. I didn’t really have any industry connection at all until Matador came along. I was putting out stuff on Bandcamp, and it got sort of a grassroots fanbase. Just people online picking it up, circulating it, talking to their friends about it. It just grew and grew very slowly. Someone who Chris Lombardi from Matador had worked with knew about Car Seat Headrest or had known for a couple records at that time. They were interested in starting their own label and working with Car Seat Headrest, but they contacted Chris first and they kind of had an agreement where they weren’t going to steal artists from one another if they were interested. He talked to Chris, and Chris was interested in Car Seat Headrest, so we ended up on the label.

Oh, funny. That’s a really nice way, like a leg up so-to-speak, because it’s an established indie label and a stamp of quality.

Yeah, it was a crazy stroke of luck. There are a bunch of indie labels. I was thinking that we could start with something smaller, but I didn’t have any connections, even in the smaller field. We’d just done a couple of cassette runs, one-offs with people who were interested in doing that. But yeah, Matador really came out of nowhere. That was a 0-to-60 record.

In the first record, Teens of Style, was that like a compilation of songs you’d already done that had been on Bandcamp? What was the exact structure?

Yeah. I might have been planning on that even before Matador came along. It was just material that had been on older records. I wanted to revisit it. I thought I could do it a little better. That’s been kind of my downfall on a lot of material. I’ll finish it and then I always just want to go back and re-do stuff and see if I can do it any better. That was what Teens of Style was. Once Matador came along, there was more reason to do that, because I knew we’d have an audience now. We’d go from having a very small audience to now a lot more people were going to be listening to it. So Teens of Style was sort of an intro, if you just wanted the basics of where we were coming from, you could listen to that record.

Had you reworked songs for that? Did you take older songs and play them with Andrew and re-track them?

Yeah. Andrew was on it. Jacob Bloom was on it. He was playing bass at the time. And yeah, I rewrote a little bit. For the most part I kind of stayed faithful to the song structures that were there. But yeah. That’s one I haven’t revisited in a while, just because it is a strange entry, but I’m always kind of interested in these weird like non-album albums that pop up in a discography. If there’s some sort of compilation where an artist is coming in and redoing something, I’m interested in that. My own discography ended up being peppered with stuff like that.

Absolutely. What is the impetus for revisiting and rewriting, rebuilding, or even on the new record, there’s three versions of the one song, right?

Yeah. For me, it’s all a process. You put out a record or a song at a certain point, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s the only version of it, or it’s the best version of it. It’s just the point that you got to with it at the time. If you’re an artist, you get to a certain point and record it in the studio, and then you go play it live. Maybe it turns out very different after you’re playing it live for a while. Or, if you’re not touring, you might just record it, and then you get a better instrument or a better studio space. It seems like maybe there are more opportunities there. So I’ve always been interested in breaking down the idea that once you put out the record, it’s done and then you move on. I think in actual practice, that’s not how it works for a lot of artists. I kind of wear that on my sleeve.

Does that allow you to move on a little quicker in the recording process, to let go?

Um yeah. I mean, it’s always pretty slow going. That’s just kind of the natural album cycle, where you put it out, you tour for a certain amount of time, and then you make the new one. I’m kind of writing through all that period, just putting new material together. I have the time to put stuff together and decide it doesn’t work, take it apart, put it together again, and just be going back and forth for a while during any album process. But definitely once I start getting toward the end of the process and you have to put the period on it, then it does help me to just think you know, it is just a document of that particular period in time, and it doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to have enough interesting stuff going on in it that if I come back later to it, there will be things that surprise me and interest me.

Yeah. Do you take a fair amount of time these days putting an album together? It seems like you get a bit obsessive even though you’re able to let go.

Yeah. There’s definitely a lot of back and forth. Our most recent record, Making a Door Less Open, I had the advantage when we signed to Matador, I already had Teens of Denial done, and I knew I wanted to revisit Twin Fantasy, so I had a long time to think of new material basically, of what we were going to do after Twin Fantasy. That’s what I did. I spent a long time just kind of brewing on different sounds and different songs that I might want to work on. Then once we finished Twin Fantasy, it was about two years that I was kind of thinking full-time about MADLO, and then one year when we were going through and putting everything together. I think that’s just the way it shook out with Car Seat Headrest. I want to spend the time, and I think you need about a year at least, working full-time on a record, to make it something that you can really go back to, over and over again, outside of that context. That’s what I want to make a Car Seat Headrest record. I want it to be a little divorced from its time. I want it to be something where if someone stumbles upon it and they don’t know the context, they can still get something out of it. That requires some back-and-forth. You don’t go with your original instinct. You change it or develop it as it goes along. But that’s just what it is, what this project has turned into. There are definitely projects where I do go in, and maybe I’m working on someone else’s record, or it’s just a different thing, and it doesn’t take that amount of time, because it’s more just about getting the energy that’s there at the time.

Right, just capture what’s in the room. That another way of looking at like capturing where that’s at in that point in time. That’s what it is, like you said earlier. A document.

Yeah.

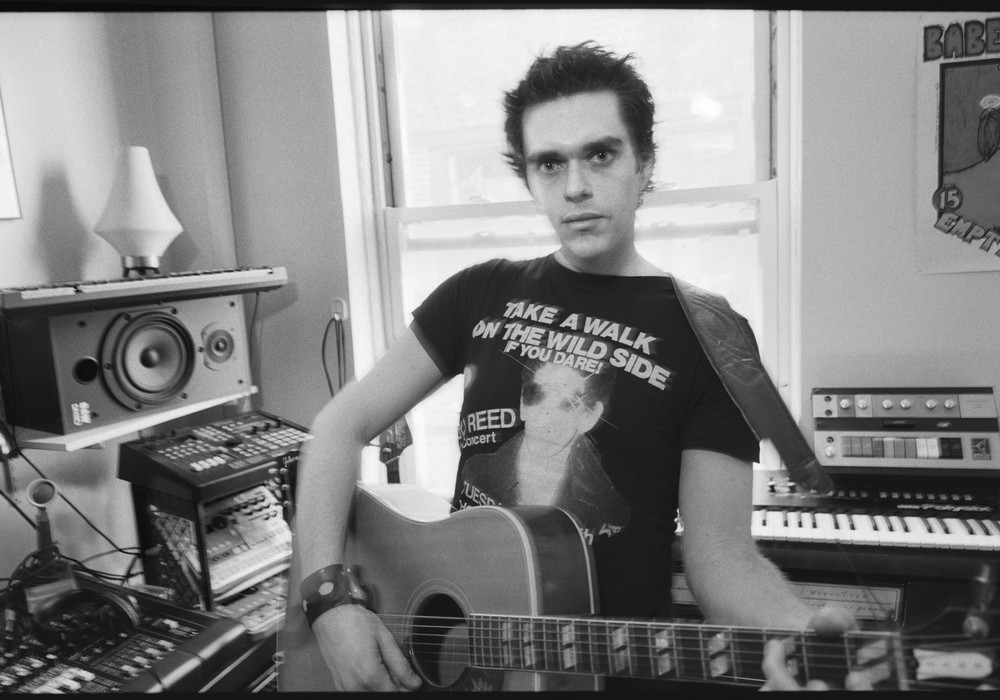

Where did you record MADLO?

We were at Avast! Studios in Seattle. Really, we would just go in and mostly do drums in the studio. That’s the one thing that’s pretty difficult to get anywhere else. You need the mics and the room for it. We would do drums, and we’d do live tracking, but we would just kind of jam on the songs. I’d have the structures set up. I would have a demo ready, but we wouldn’t try to get it all the way there in the studio. We would just focus on the energy that was between us at the time. So we would track like that and then we would leave the studio, and I’d listen to it after the session was over, and then I’d pull it apart and see what I could use and what I couldn’t use. I would combine that with samples with MIDI, with whatever we could put together on the computer, so it ended up being a real hybrid album between what we were doing in the studio and what we were doing at home.

There are a lot of programmed drums or samples or loops or drum machines, different things on the record too, right?

Yeah. I mean, a lot of it, really the majority of this record, I associate with going to Andrew’s house to do it. Andrew had more of an EDM background to production. He was making his own stuff before joining Car Seat Headrest. That was something I was interested in, because I don’t have much of a background in that. Part of this album was a process of learning that, learning the sounds that are associated with that. So he would be at the computer and then we’d switch, and I would be at the computer. There was just a lot of that energy to it, just a couple of guys at home putting something together that sounded good on that set of speakers basically.

It probably helps too to have a drummer who understands that music and has both backgrounds but isn’t going to be like, “I wanted real drums on this part.”

Yeah, that’s ideal. Everyone in the band is just so flexible about what appears on the record. We all just kind of process it part by part. It’s like, “We’re going to be together on tour playing this, so let’s make sure that we’re happy with those parts, how we’re playing it live when we’re on tour.” As far as the record is concerned, I don’t think they’re going to be listening to it on a daily basis, so if a guitar part gets subtracted or its computer drums instead of live drums, no one’s going to be upset because that doesn’t affect them as much as what we’re doing live. As long as it doesn’t turn into just a mess of cables and pre-programmed parts live, I think we’re all going to stay happy with what’s going on.

Do you think it’s also bringing a different energy to a live show? You also mentioned earlier about having open parts where things can stretch or amorphous sections.

Yeah. I mean, it’s always just, kind of starting from scratch once we start thinking about the live show. We make the record, and then when it comes time to putting the show together, we really just have to think about what’s in the room, who’s in the lineup at the time. The last major tour that we did, we were playing with the band Naked Giants. They were opening for us, and we also were on stage with them. So a lot of what we did there was just, “What can we do with seven people? How can we arrange the songs that way?” So even the songs that we chose; we were doing covers, and we were doing different songs, not necessarily promoting the record as well as we could have been, because it was mainly about having that energy on stage and having fun with it. So this time, shrinking back, we had agreed with Naked Giants that it was just going to be for Twin Fantasy, so now we were shrinking back into a smaller outfit. It was about, “How can we match that energy?” or top it when it’s a smaller lineup again. That was kind of one of the reasons why we were leaning more electronic, because that really adds to the palette if you can have live drums and then switch and trigger samples. If you can add synths it just gives you a lot more to play with, even if you have a limited amount of members. Before quarantine started, we were practicing and figuring out ways of incorporating it in. It felt definitely like the core of it was all live, like we had control over what was going on, but we just had these certain sections where it was going to sound different. It was going to go electronic or go into a section that we couldn’t have done before, just doing everything live.

How did you do some of that? Did Andrew start sections or trigger sounds?

Yeah, we upgraded our equipment. We gave Andrew a kick pedal that just triggers samples. Snare and tom triggers. We were in the process of going through the record and deciding what samples we wanted to pull and what would be better as a live kit. It was going to be a hybrid kit he was using. We also were going to use an Ableton Push for parts. He would go off the kit, triggering samples straight-up, more like a DJ. Yeah, that was the main thing. We’re going to be using a click and still will, at some point. It’s just going to be…

I know. Everything got derailed by the whole pandemic, right? You probably were going to be touring all summer and promoting the record?

Yeah. We definitely got derailed. Right now everything is just pushed back a solid year. The plan is pick that up next summer. But yeah, it’s been a weird downtime for sure. I’ve been working on a couple different things, brewing up new material for us and working on a few projects for different people. But yeah, the live show, I’m interested. I have to not be as interested in it as I was, because I won’t be able to get to do it for a year, but it’s always the sort of thing where you don’t want to plan too much before you go into it, because things always change once you’re doing it night-to-night. You figure out pretty quickly what songs work and what songs don’t, and you have to adjust from there. It’s really like you want to start planning a few months before the tour is going to start, and then you have a certain amount of, you know, you have certain ideas of what you want to do, and then you can change it once you’re actually doing it.

Right, or do secret shows, kind of get things ready?

Yeah. We were going to play at MASS MoCA, which is this museum in North Adams, Massachusetts. That was going to kind of be our set up. They were offering sort of a week of rehearsals, and then we could do a show to cap it off. Yeah, that got delayed too. That would have been the first time we were really able to do a dress rehearsal for a tour. That would be nice. We were going to expand the lights and the set design a little bit too.

I want to jump way, way back. The origin of your band name, isn’t that from recording sessions in the back of your car, trying to get some isolation? Is that true? I love that.

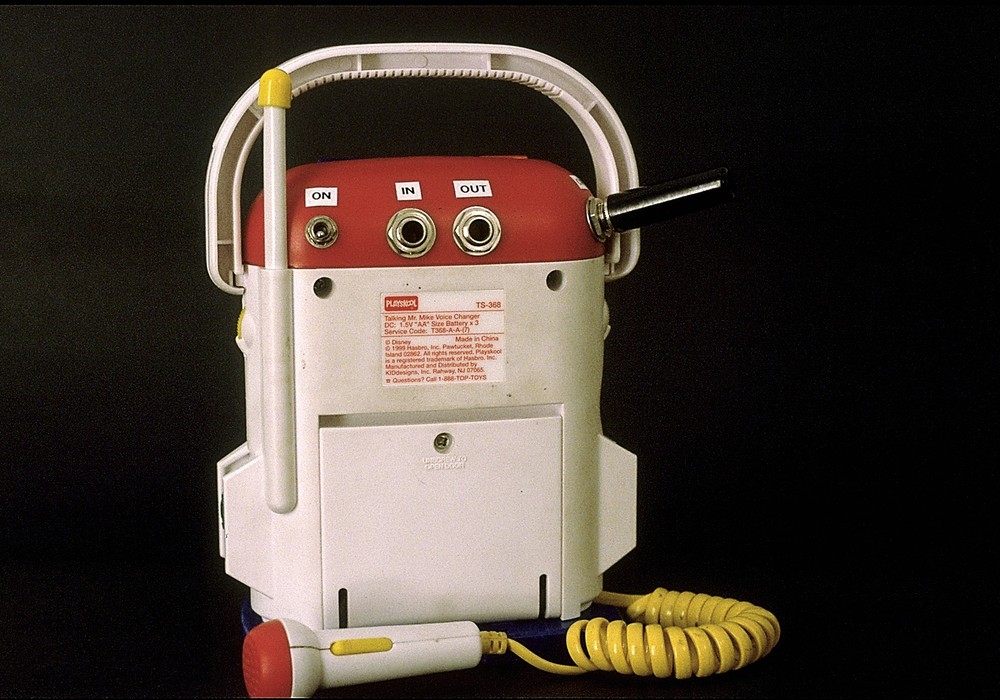

Yeah. I was a home recorder. I was in my parent’s house. This was in high school. I had already recorded a couple records under a different name, and I was starting Car Seat Headrest just conceptually as sort of a different project; more experimental. Sound travels in a house. I didn’t have any soundproofing. I wanted to be able to sing and not feel like the rest of the family is listening in, so I just started going in the car. That was really the only private space that I had. It was just vocals there. I’d track everything else at home, and then get in the car and drive somewhere secluded and just sing however I wanted to. It was really probably one of the worst places to sing in in terms of acoustics or anything, but all I wanted was the energy of being somewhere where no one could hear me.

Were you using like a laptop and running it off of your batteries?

Yeah. You charge up a laptop and you can get a couple hours off of it, so I’d bring it with me. I was using the laptop microphone. I would just be singing or screaming into it. It was really just kind of intentionally the lowest budget possible, the simplest option possible, and then just screwing with it in the mixing program.

What were you tracking the rest of the instruments with?

A lot of it was laptop microphone. I had this little computer microphone, if you bought a PC in the ‘90s, it would come with a basic microphone. I had one of those. That was it for a long time. I think it was probably three years into Car Seat Headrest before I actually owned a microphone that I was using for recording purposes.

Wow, that’s kind of amazing.

Yeah. It kind of taught me, you know, it forced me to figure out a lot of stuff on the DAW. How to mix it properly. Because I was starting with material that sounded super whack. It did not sound clean. It did not sound good. So I just would really screw with stuff until it started to sound interesting. I wasn’t going for clean, but I wanted sounds that were interesting to me. And so now, working in a more normal mode, you start off with tracks that are clean, and then I don’t take it for granted when it is clean. It’s nice to just be able to work with that as a grounding and also have the experience in case it’s not clean or if it’s not good. A lot of times if you track live or something weird happens in the studio, you do end up with tracks that aren’t as perfect and polished as an engineering handbook would want it to be. Then it’s just problem-solving in the mixing. That aspect I do have a lot of experience in at that point.

Yeah. You’ve developed a way of working.

Yeah. Kind of backwards from how anyone else would recommend it I think.

I think we’re seeing a lot of that ever since home computers were everywhere. I’m way old, and when I was in high school, there weren’t even 4-track cassette decks.

Yeah. I got super lucky that I came up in a time where it’s super-cheap to record and a lot of people have that capability already, just from having a computer or whatever’s in the home. There’s just a lot of ways to do it. I just always took advantage of that. Different ways of recording too. I did have tape recorders as well. I remember some sort of setup where I would be recording onto tape, then setting up a computer microphone to get it on the computer, and then overdubbing, like having a different tape and recording that in and ending up with these overdubbed tape things. All just stuff that I could do, because it was $10 to buy a tape recorder at Wal-Mart or whatever. That gave me the background that I needed to start figuring out what I wanted to do with music. I think that you do see a lot of people doing it like that. It’s music that doesn’t always come through, because it’s not marketable. It’s not polished stuff, but that’s the stuff that it interests me more to listen to. Hopefully you do see more artists making it in, getting a break or coming into some sort of more mainstream recognition that you know, has that background where they’re making the weirder stuff. I mean, the other advantage of being young and having the equipment is that you’re bored pretty easily too. If your mind turns towards music as a way of entertainment, you can really get into the mode where you do spend a year making a record. You go back to it, and you put the work in. That’s how I was coming up. That was my outlet, going to school or doing whatever, I was usually more interested to going back to whatever project I was working on and trying to make it better. I’m in a chat right now with some younger musicians who are doing the exact same thing. I’m trying to learn from them more than I’m saying to help them out, because I think it is just a continuous learning process for me. Even stuff like YouTube tutorials, the engineer guys telling people how to mix, it’s all useful, and all it costs is your time. I think just sharing as much as you can is the way forward.

How did you mix the recent record?

It was a lot of everything at once. Writing, recording, and mixing. Really, I would lay down stuff on the computer, build it up in sort of MIDI demo form, but then if it had a good energy at that point, I wouldn’t want to deviate from that too much, because I’ve done it. Teens of Denial, we had the demos and went in and re-recorded everything in the studio. The benefit is that it’s easier in that way. It’s easier to process as an album. But you do lose something too. If you work on the demo and you get it to a certain point, you can never get it to quite the same feeling if you’re starting from scratch in the studio. That happened with Teens of Denial and it kind of happened with Twin Fantasy too when we re-recorded it in the studio. I really wanted with MADLO to keep that demo feeling all the way to the end. Whatever the initial feeling was that sparked it and made me feel like it was a good song or good material, to just preserve that. Something like “Can’t Cool Me Down,” I laid down the drums and bass and these vocals for the chorus, and all of that pretty much got kept from the original demo to the final form. We confused a lot of people, because we were playing it live before it came out, and they were sort of expecting a big rock version, but instead they got the original basically. That was always the intent with it. It was just a matter of good parts of the demo stay, and the parts that are just filler or aren’t fleshed out, just fleshing those out in whatever way we can, playing it live to get a feel for it, rewriting lyrics, recording different parts. It would all just happen kind of organically, you know, just going back to that session I mean for the most part, he wouldn’t work on it without me, and I’d give him the go-ahead, or I’d come over and we’d work on it. But yeah, there were a lot of, we’d go down a path and then have a weird, alternate version of something. There’s still a lot of that to sift through honestly. We kind of got the versions that we needed for the album, and there’s still a lot of detours that exist that it would be interesting to go back and look at.

That sounds very much like the Car Seat Headrest way.

Yeah. It really was just an organic process. Something just kind of grows, and you trim it until it looks presentable. But I really don’t like messing with it too much or making it into something that’s very straightforward. Arrangement, writing, singing. I don’t want to make it feel like it’s sort of the document of the real thing. I want to make it the real thing itself, which is just difficult to do that with recorded music. I think if you’re in a room and you’re playing something, it feels a certain way. I think the hardest thing you can do is put that on record, so I kind of just try to make stuff that has that feel, even if it’s not performed live. It has that feel where it’s being created in front of you basically.

Yeah. There’s a lot, I’ve seen you mention a lot of classic rock bands, or Beach Boys, Pink Floyd, or whatever, where a lot of that work is laborious work in the studio to build something that kind of sounds organic and simple in the end, but was very intentional.

Yeah. Someone like The Beatles, I feel like they kind of got to a crossroads as far as playing live or being in the studio. They chose being in the studio, and the world is better for it, because they were able to figure a lot of stuff out. Those songs just feel so organic, where they had the raw material, and then they would have some sort of idea when they took it into the studio what they were doing to it. It came to be in the studio, rather than coming to be in a live setting, and then you try to take it into the studio and capture it that way. They did that with Let It Be, and then they ran into a bunch of trouble, because they wanted everything to be live, but then they realized it was a lot harder to make a good album like that. Yeah, they kind of established the model where if you want to make really good records, you basically have to start in the studio. You have to think of that as what you’re arranging for and then arrange it appropriately.

Right. It was certainly a shift. Ever since, we’re all trying to catch up.

Right.

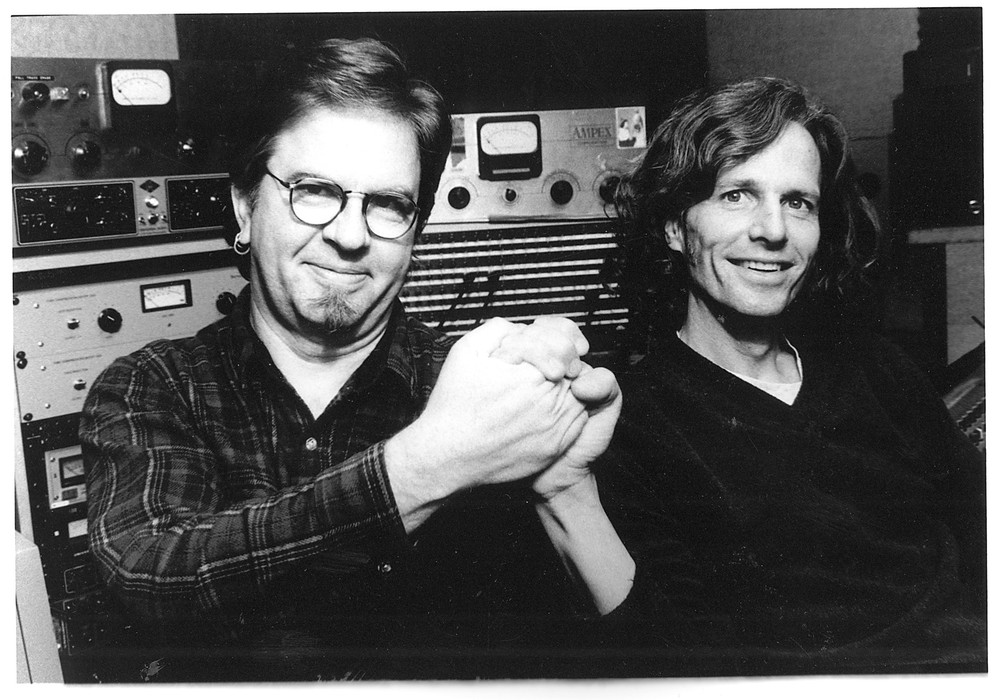

You’ve technically produced all the Car Seat Headrest records out there, except Teens of Denial with Steve Fisk [Tape Op #3]. What brought that around, and what was different about the process? What did you learn and like and not like?

Yeah, we had done Teens of Style and it sort of felt like I’d gotten to the point where I couldn’t self-produce anymore, at least the way I was doing it. Teens of Denial, that material felt like it had to be brought into a studio, which we hadn’t done up until that point. I wanted someone who knew what they were doing in the studio and who I felt like I could work with, so Matador sent a list of names. Steve Fisk was on there. It was Seattle people, because I didn’t want to fly somewhere else and be doing the whole thing somewhere else. And I liked what Steve Fisk had done. I hadn’t heard of him before, but I knew some of the artists he’d worked with, and I liked the feeling, I liked the bands that he chose to work with, and I liked what he did with them. I had a good feeling about it. He got sent the demos, and it was a comfortable fit. It was an easy fit. He took me to I think three different Seattle studios. One of them was Soundhouse, which we did most of Teens of Denial at. One of them was Avast!, which is where we’re at now. Those were the two that we ended up doing Teens of Denial at. Mostly at Soundhouse, because it was cheaper. But yeah, we fit together well. I was approaching it kind of hands-off. I’m not going to try to do this the way that I had done previous records, because it was a different process. I knew we were going into the studio, and I didn’t want to act like I knew what I was doing, because I knew that I didn’t. I wanted to make it easy on Steve so that he knew what he was doing, so I let him run it that way essentially. What we were bringing was the band who had practiced the songs and knew what they were doing in that regard, and so it was just a very different process than the earlier Car Seat stuff. It was just tracking live and then overdubbing from there, but everything had that core of the band performance to it. Steve was just the right fit for allowing us to do that at the time.

What kinds of suggestions did he have on the basic tracking? Was he getting in on tempos and structures and keys and things like that?

Not so much, because I gave him the demos, and they were pretty much solid. I think that we kind of connected right away on what needed to be different from the demos and what it was going to be like. We were a three-piece at the time, and Ethan [Ives], who’s on guitar now, was on bass. I think we both just felt that’s going to be the setup. “That’s going to be the structure that we’re working off of.” He just did his thing and I mostly tried to track on it. I took pictures of his mic setups. I didn’t worry too much about that end of it. I was just more of a performer in that regard. Then, afterwards we took it to his place and we mixed it there. We were working on Pro Tools, which I hadn’t worked on before, so my contributions were maybe a little bit more clumsy and basic than they would have been otherwise. A lot of times I would go down a path and then just come right back. It was just a process of I would add a little bit to what was there, but we really did end up with just stuff that felt more-or-less live.

What program were you working in before that or are you working in still?

Well, it started out in Audacity, which is a free program, and then I got a Mac laptop which had GarageBand on it for free, and then I upgraded to Logic, which is like GarageBand but costs a couple hundred dollars. That’s what I was working on during this time, during Denial. I stayed on Logic up until about two years ago. I switched to Ableton. Andrew had been recommending it for years. It was his go-to. As soon as I started really using Ableton, it definitely clicked with me, and I couldn’t go back to anything else. It just does a lot of what I want it to do. In comparison to something like Pro Tools, which is integrated into the studio essentially, so it’s customizable, but it’s not going to have a lot of input onto what you’re doing. You have to set everything up yourself. In Ableton, there’s a lot where it is set up. You can just run in and start putting stuff together, start putting MIDI together. It just has a lot of effects and things I like to do with records. Earlier, I was having to do more of a set-up, to try to get the effect that you can really do pretty easily with Ableton.

How do you find mixing in Ableton? Does that work well for you guys?

Yeah, I think it’s about even with any other program. Problems that we have with mixing are typically problems stemming from our lack of knowledge, rather than with the program. Neither I nor Andrew had any sort of schooling in terms of production. He watched a lot of YouTube tutorials. I did not. I mainly went by ear, read what other bands I liked were doing, and tried to do that. Stuff like EQ and compression to me, I didn’t touch it for years. I’m still just kind of getting the hang of how those tools can be used exactly. That was where the struggle came from. That’s going to happen on any program. But I think Ableton streamlined it, so it was easy to see what was going on and what we needed to fight basically.

I guess one of the main points for you is that it allows you to be creative faster, or to capture ideas faster.

Yeah. I’ll kind of get half an idea, and then I’ll open up Ableton and start recording. Whatever that idea is, if I can track a guitar part, if I have a beat in mind to go with it, I’ll just quickly open up a MIDI track and drag some drums in there and program it to go along with that. I guess if you know what you’re doing on any program, I think you can get that template. But I’m just lazy, and I want to open up a blank program and already have something going, so Ableton is good for that.

Where do you work at in your home? Do you have a set space?

Just in my room, where I’m talking right now actually. I mean, I’m in an apartment, so my options are limited. I think if I wasn’t in an apartment, I would have a room dedicated to this, because it’s a drag to do everything in one room and not have a place to escape to.

Right.

But it certainly goes with how I’ve been doing it so far, just wherever I can get a microphone and a laptop, that’s where I’m going to be working.

Definitely. Right. The listener never knows or cares where it came from, right? As long as they enjoy it.

Yeah, I think so. You can get a way more professional sound in a bedroom than you used to be able to. Just so much of the tools for that come on the computer, and if you’ve got a decent mic, that’s pretty much all you need, and a lot of practice on the program.

_display_hires.jpg)