Vintage King co-founder Michael Nehra shares some of his love, knowledge, and practical advice for diving into the world of vintage audio gear, and then takes us behind the scenes for a walk through of a laborious restoration of "The Holy Grail of Compressors."

Tell us about how you and, eventually Vintage King, got into classic gear.

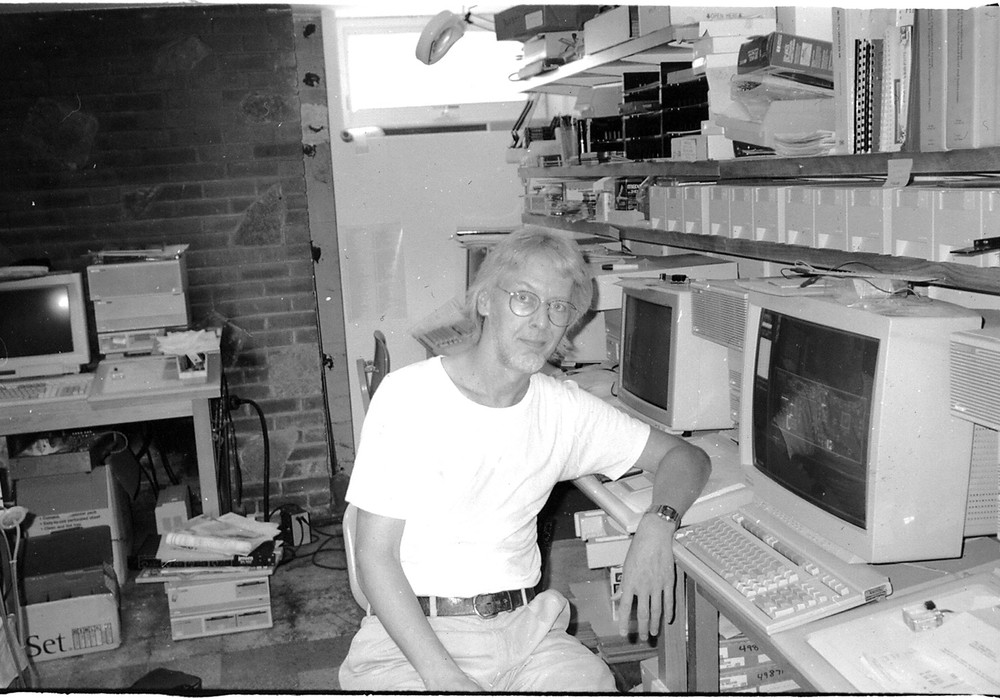

When my brother Andrew and I started buying vintage gear, it was in the early '90s. Once we heard the tone, the soul of a classic Neve module, for example — there was no turning back. Our studio was based in Detroit, and there were a number of studios in our region. But, back then, there weren't gear dealers as we think of them today, and the Internet was just starting to lift off. We actually found our gear through tiny classifieds in the back of recording magazines. We'd respond to one, arrange the purchase, and cross our fingers that the gear actually worked when we pulled it out of the box. Even then, despite the obstacles in finding reliable gear, we refused to believe in "lemons." None of the dealers we bought from offered a warranty of any type, and if the gear arrived non-working, they would arrogantly tell us, "'tough luck,' it worked before I sent it!"

We felt like every piece of gear had a history, a personality to tap into — it just needed the right tech to bring it back to its original glory. To be sure, some gear gave us more headaches than others, but as we got to know the guts of more and more classic designs, it became easier and easier to diagnose potential problems and preempt them. In time, the skills within our tech shop grew from that of one man to a team of over a dozen skilled experts. Initially, all the tech work was for us — for our studio. It wasn't until we started selling off some of our own gear that "Vintage King," as a dealer and gear-restoration center, really came to life. We'd guarantee our used gear when we'd sell it through those classifieds, accepting returns, unlike the others we'd bought from. Soon enough, through our ads and through networking with various musicians we would meet when touring, recording, and producing with our band, Robert Bradley's Blackwater Surprise, we had made friends with engineers and musicians across the country. They recognized our passion and saw the quality of our tech's work reflected in the gear they'd buy, often asking us if we could restore this-or-that they had sitting in the closet.

It all really exploded from there. More than twenty years later, we've nearly seen it all — servicing literally over a thousand of those Neve modules we initially fell in love with, as well as a hundreds of Pultecs and 1176s, a few dozen Fairchilds, and so on. Classic gear is as popular as ever and, really, not much has changed. I still believe it's one of the best investments you can make in your studio and yourself as an engineer/producer/musician. I know I may be nostalgic about it all, but I do think there's something special about tying your sound to recording history, too.

What is the attraction of vintage outboard gear?

Even as the actual recording process gets continually streamlined and made more powerful with the DAW, I don't see classic outboard gear ever losing its appeal. Engineers are musicians too, and these are our instruments. The right vintage piece can just give that sense of vibe, a sense of glue that threads individual tracks together. If you want air and openness, a bigger bottom, a taller signal that stomps through crowded tracks — the perfect vintage piece is out there. Really, just hearing your signal make that transformation the first time you pass it through a classic can be quite a euphoric experience.

Also, I think there's something very significant about having a physical interaction with your instruments. Reaching out and turning a knob or flicking a switch can deepen your connection to the sounds you're manipulating, as opposed to clicking a mouse, which we often do thousands of times throughout the day for various other, non-musical tasks.

How easy is it to integrate into modern setups?

All the time, I hear ongoing talk about the analog-digital debate, but the good news for everyone is that the two work beautifully together. Integrating a piece of classic gear, even just one, is a natural and simple next step no matter what your studio looks like, especially for those entering engineering from an Mbox-based, home-studio type perspective. You can easily incorporate an outboard EQ or compressor in your front end tracking/overdubbing chain — many clients choose to upgrade their analog/digital (AD) converters to hear the full benefit of the vintage gear going into the DAW. When you're in mixing mode, you can use an ADDA converter to send/return, kicking the signal through your lineup of gear, then printing it back in your DAW. Notably, we've found that many of our clients much prefer classic EQs, compressors, and verbs-delays, such as Lexicon 480Ls, PCM42s, TC 2290s, and AMS, over plug-ins. The plugs are just not as thick in texture nor as three-dimensional, lacking the unique artifacts and sonic "depth" that makes the gear so special. That's not to say there aren't some good or even great plugs overall, ones that many professionals love combining with great outboard hardware, but this seems to be the consensus. The bottom line, though, is that the integration part is easy — we help clients all the time get their analog and digital systems in perfect alignment, and many of the most popular tracks these days are made using some sort of hybrid of the two.

Why is vintage gear expensive?

So much of this gear was made in limited quantity and, as a result, is somewhat rare. It's all about supply and demand. There was simply a limited quantity of most pieces built back in the day (particularly Decca, Fairchild, or Pye compressor/limiters). Now, with the advent of the DAW making recording a much more affordable reality worldwide, more and more new engineers are gravitating toward the vintage pieces — and so the demand is larger than the supply. Why are classic Porsches, muscle cars or choice pieces of antique furniture so expensive? What's fun about the audio industry, though, is that we get to use these tools for our trade, without them losing value. Down the road, you can reap the benefit of an appreciating asset — but you can fully appreciate it right now, too! There are no locked display cases, no plated glass. You can't really use most collectibles.

How much fashion is involved with the popularity of vintage gear — how safe or strong is my investment?

I think classics are classics because they've endured the test of time. They're tried and true. There's a magic there that's undeniable. In terms of investment, it's just like any market-based commodity - there are ups and downs tied to the world's greater economy, but, over time I've seen values really surge, far outpacing inflation. For example, look at vintage large-diaphragm tube Neumanns or AKGs. Around the time we started Vintage King, in the early '90s, C12s, 47s, and Elams ranged from $3,500 to $6,000 USD each. Today, well-serviced, nicer examples now range from the lower teens for a C12, mid teens for a 47, and high teens to the lower $20k range for a beautiful Elam. Pultec EQP1As were $900 and are now into the $5k range — 1073s were $1000 and now trade for more than four times this amount. These are just some of the staples, with the same trend continuing with Fairchilds, API, Lang, Pye, Decca, RCA, and more. There is a continual and steady increase in value. Plus, the influx of new engineers really helps drive the market. It's a win for everyone. An engineer may go looking for a great U67 and pair it with a Telefunken, API, or Neve for a classic vocal sound. By the time he's ready to trade, sell for another piece, or move out of recording, there are scores of freshly minted engineers interested in vintage gear. Ultimately, though, a classic piece of analog is worth far more than a worthless out-of-date digital unit and, in most cases, more than the newer analog clones copying classics. There is definitely room in the market for all the great new analog gear, to be sure, and there are many brilliant pieces that have come to market this decade — many of them doing things never before done or never before possible, based on vintage-inspired designs or completely original schematics. Still, with the decades of history attached to them, classics are the surer thing.

Any buying tips? What's the best way to avoid a lemon?

As a rule, it's best to be especially careful when purchasing units with hard-to-find tubes, rare transformers, or lots of gold-plated switches, as they can be expensive or even impossible to replace. If you have the option of purchasing gear already reconditioned — or, at the very least, with a return policy and warranty — I highly recommend it. For instance, at Vintage King, you can return nearly any item you purchase and most vintage items come with a free 6-month or 1-year warranty. In contrast, eBay can be a very scary place! I can't tell you how often we receive calls from clients who've bought gear at what appeared to be a great price on eBay only to find the gear needs costly servicing, is missing integral original components, or has been cobbled together with some original and some non-original parts (often the case with U47s and various tube microphones).

For someone new to vintage gear, what approach would you recommend in exploring the options?

These days, the Internet is an incredible resource, one that wasn't available to many of us first getting into vintage. On top of vast sites out there with so much information, there are scores of forums with really helpful, knowledgeable users — Gearslutz.com being one of the most active. At Vintage King, we've also recently knit together our own community for those interested in knowing more about classic gear, to help connect like-minded people. We call it the Vintage King Preservation Society. The way I see it, the sharing of technical knowledge — just like preserving vintage gear — is really important, both for developing today's engineers and for keeping the gear's legacy alive into the future. Of course, Internet aside, if you have the opportunity to chat one-on-one with someone well-versed in the gear, it can be really valuable. There are so many variables and questions that play into choosing one piece over an other. It's often easier to think things through and talk things through in real time. I still love chatting it out with clients about what they want to do and what special ingredient they're wanting to find. I think all of us who know the gear, love the gear, and sell the gear feel the same way. My best advice would be to reach out — choosing gear is almost as fun as using it.

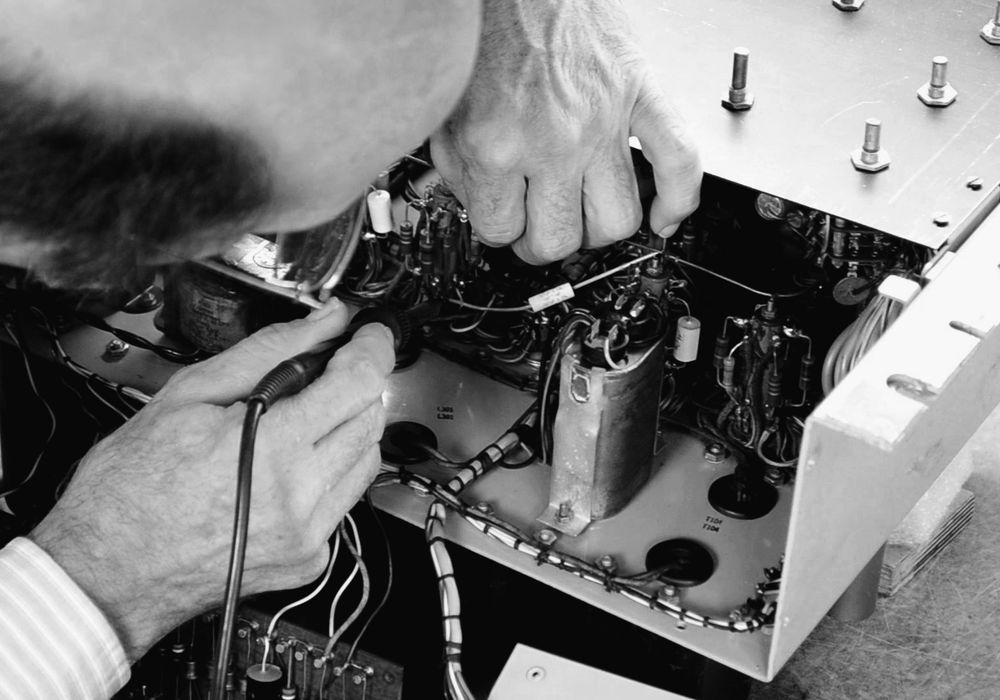

Behind the Scenes of a Fairchild 670 Restoration

Initial Functional Evaluation

No matter what we're restoring — even two identically made units — the approach can be vastly different, based on the condition of the gear or the needs/requests of the gear's owner. We feel proud and lucky to have such passionate techs, putting a lot of integrity into their work, a lot of tender love and care. Their experience has led them in different directions, so we have a number of specialists for any given project or any facet of a particular project. For the Fairchild example, it's going to go to our Senior Tech Andy Pavlosky. He's a tube technology expert and has seen a number of Fairchilds over the years. Andy will start by determining the Fairchild's inside-and-out condition through a visual evaluation and diagnostic testing. He might have to replace the power cord and rectifier tube before testing the full functionality — whatever the unit needs, he'll note it. Andy will test all tubes for condition and approximate longevity. If we need to, we'll replace all the tubes.

Cosmetic Evaluation

We can do museum-grade cosmetic restorations and sometimes we're asked to, but more often than not, our approach and the approach our clients want is age-appropriate visual restoration, being respectful of originality and keeping to the manufacturer's design intentions. It's all done on a case-by-case basis. Only if a unit is in particularly bad visual shape may we decide to strip, repaint and re-letter the panel. If that's the case, we'll fabricate a temporary panel so the rest of the restoration can continue while protecting the new panel from any potential damage during the repair process.

Necessary Repairs or Replacements

Our goal is always to preserve the gear, keeping its original tone and personality intact. In reality, however, there are times when original parts are simply not available, but we'll do whatever it takes to track them down if they are — and, in any event, we'll shoot for the manufacturer's original specs when we select replacements. Using the Fairchild example, in the rare case where we might need to replace a side-chain output transformer, we may go to Sowter Audio Transformers for the direct replacement they offer, or we may opt to rewind the transformer with an old school specialist. We'd be sure to replace or rewind the transformers on both channels to maintain a dynamic match between the sides. From there, we might need to do a full recap, replacing electrolytic and coupling capacitors. We'll also likely need to refurbish all the rotary switches, as they're usually oxidized. Rather than "wash" switch wipers and contacts with a spray cleaner, we'll get in there and clean them with a burnishing tool. We also disassemble multilayer switches to make sure we're restoring all sections appropriately. These details matter to us.

Comprehensive Cleaning

As I've touched on, we really focus on eliminating any trace of neglect, dirt and grit. Sometimes, it's easy through a meticulous process, other times, there are more challenges. For example, the Fairchild's back panel often gets discolored from the heat of the tubes. We'll clean up all of this discoloration, as well as any markings written by previous technicians, and get it looking as original as possible. We focus on correcting the less-obvious blemishes too, doing a component-by-component cleaning, replacing wires when necessary, and re-securing with OEM-style lacing. When you take off the panel, we want it to feel like lifting the hood of a show-ready car.

Multi-level QC Process

After the tech has done the planned restoration, the unit will go through extensive evaluation — first, by the original tech. He'll calibrate everything and verify performance with a computerized FFT evaluation program. Another tech will give it a final quality control test and an overnight burn-in, then ready the unit for shipping. As the Fairchild is a heavy unit, it requires some special measures in packaging and shipping. We form a miniature box that fits over the unit, then wrap that in plastic, place it in a box with numerous packing pieces, then pour expandable liquid foam into the box to secure the unit. As a precaution, we also wrap and ship all tubes separately to ensure everything ships safely.

_disp_horizontal_bw.jpg)