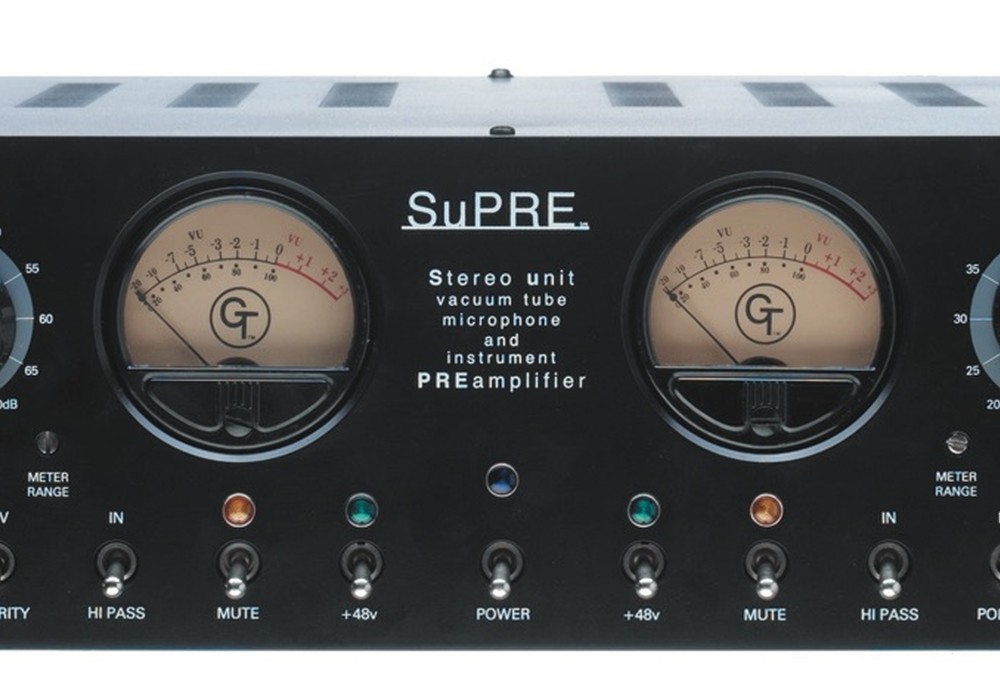

The first thing you notice upon entering John Frusciante's Laurel Canyon home is the two Studer A- 800 two-inch machines that nearly block the front door and hallway, leaving just enough room to get by them and into the house. In the tradition of great music being made in this canyon, John has made a commitment to home recording — analog recording to be more precise — that far exceeds most musicians' recording setups. One bedroom is filled with a vintage API console, a huge Doepfer modular analog synth, and an effects rack with a Fairchild 670, Pultecs, 1176s and vintage Neve and UA modules. Elsewhere there's both an EMT plate and an EMT digital reverb. The dining room has a grand piano and several organs and keyboards. The living room is filled with guitars, along with a Mellotron and an ARP 2500. The walls are lined with vinyl and some really cool rock posters and photos. This is a house dedicated to making music.

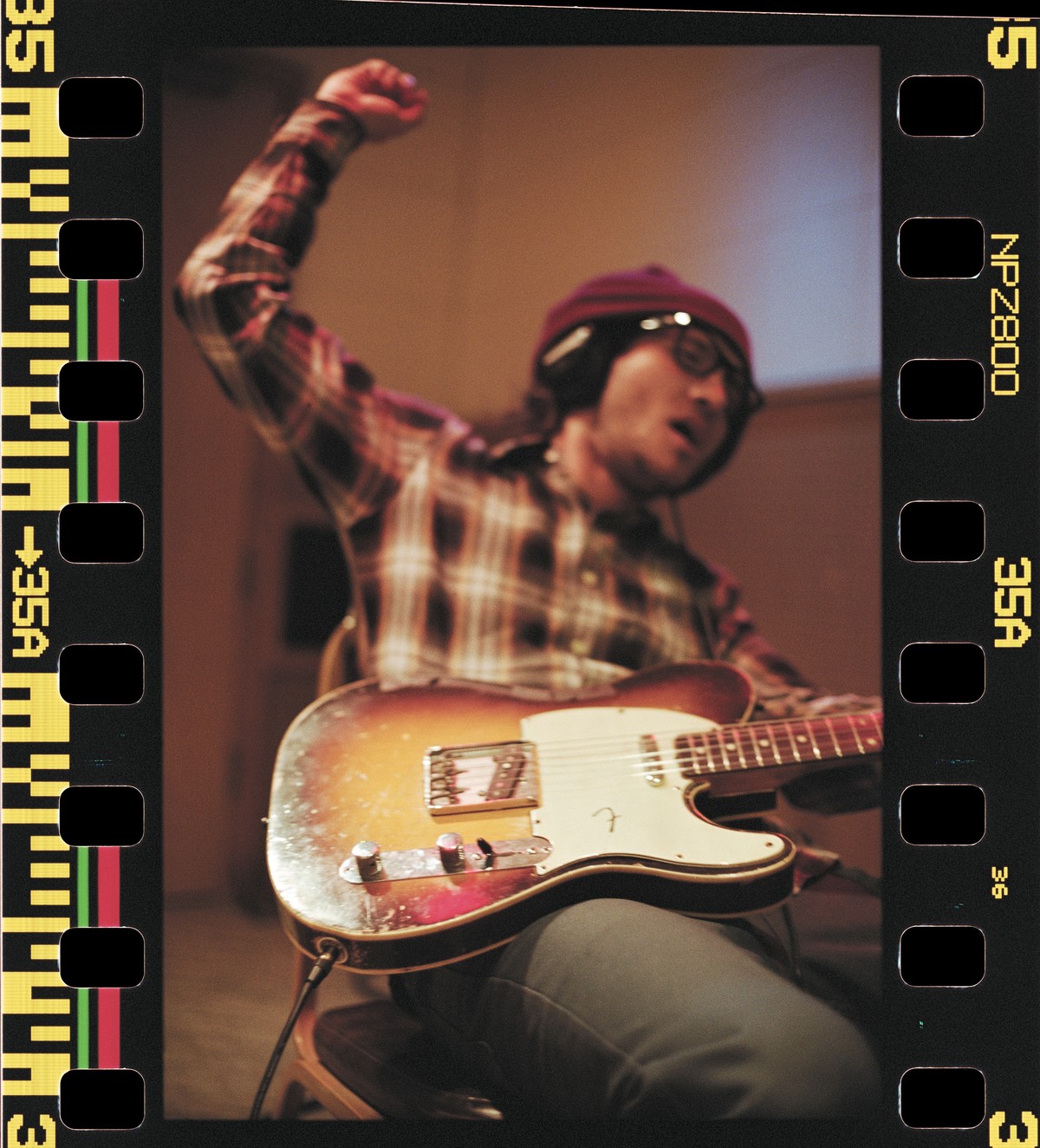

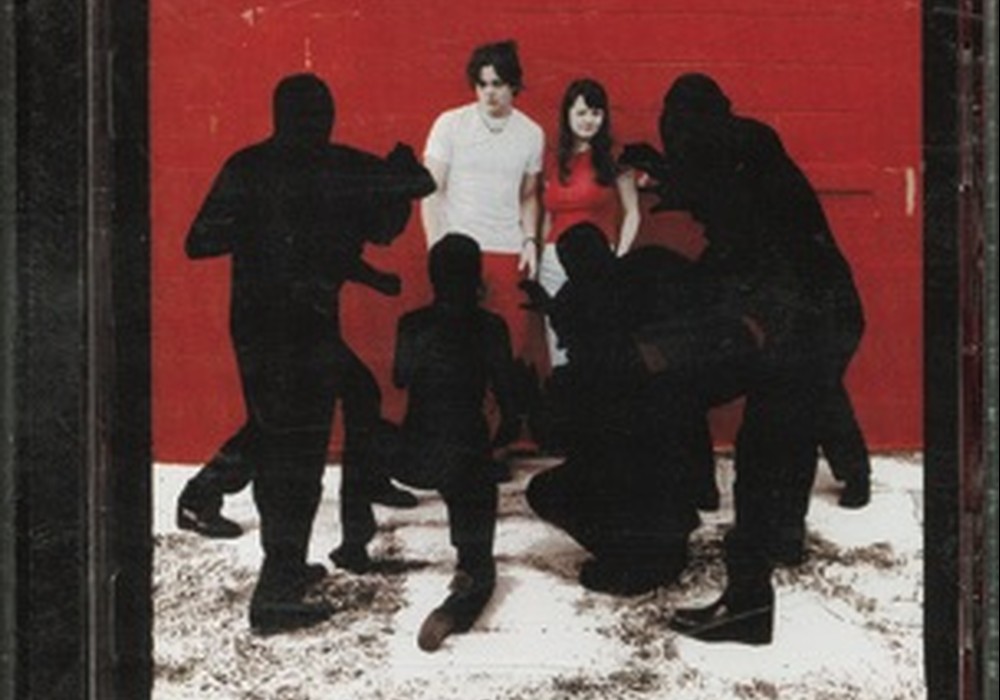

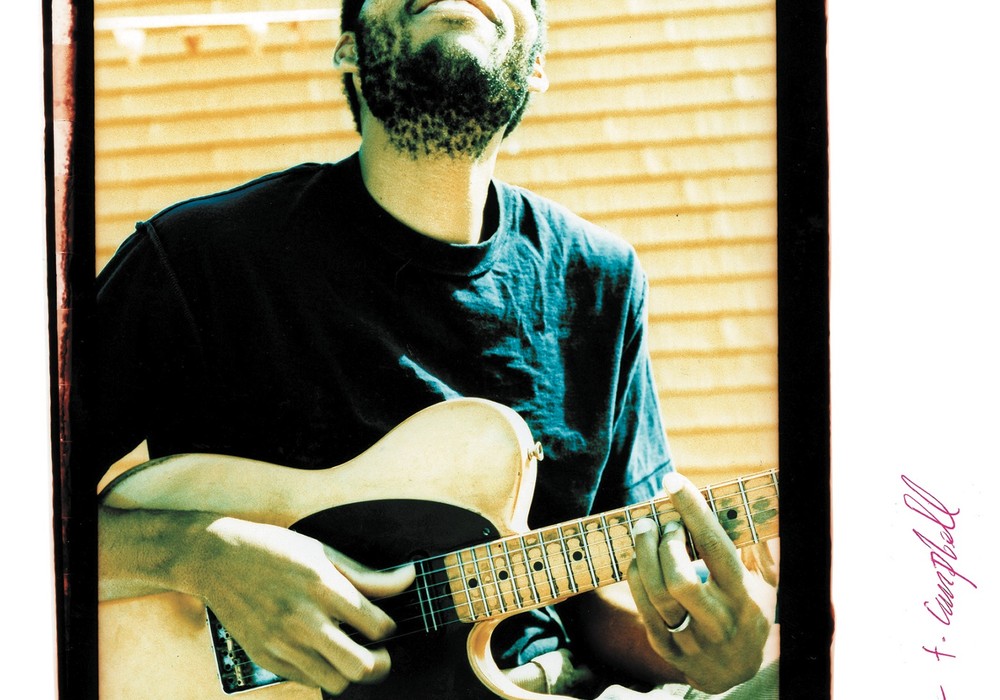

Frusciante is best known as the guitarist for The Red Hot Chili Peppers, but what piqued my interest in doing this interview are six solo records he made in six months and released in 2004. The DC EP was produced by Ian MacKaye (Dischord/Fugazi) and recorded by Don Zientara at Inner Ear Studios in Washington, DC. The rest were recorded in various Los Angeles studios (Cello, Ocean Way, The Pass, and Mad Dog) by Ryan Hewitt (see his interview in this issue). The Will to Death and Inside of Emptiness were tracked very quickly to two-inch 16-track and mixed to tape as well. Curtains is more acoustic based and was the first record entirely recorded and mixed in the Laurel Canyon home studio — done on a one-inch Ampex 440 8-track. Frusciante and frequent collaborator Josh Klinghoffer teamed up with Fugazi bassist Joe Lally for a project they named Ataxia. A Sphere in the Heart of Silence is a largely electronic collaboration between Frusciante and Klinghoffer. These six records have become six of my fave discs over the past few months. Taken together or separately, they're pretty stunning from both a songwriting and recording standpoint, and for those only familiar with John as a guitarist, his soulful voice is the real hook. Slightly gravelly at times with a beautiful falsetto, it's the kind of voice that sticks with you. The songs themselves reflect years of listening to music, but with the influences thoroughly absorbed and internalized, the end result is unique and personal.

A few days before he would take home several Grammies for RHCP's Stadium Arcadium, I met with Ryan and John at John's place, where they were in the middle of recording a new Frusciante solo effort. John was cooking breakfast and offered to make me some bacon and eggs as well. Such a nice guy! After John's breakfast (my lunch) we sat down to chat in the living room, where large windows overlooked the pool and a lush, green, wooded section of Laurel Canyon, and talked about making records. The conversation that ensued was interesting not only as insight into John's recording process, but also a look into the successful partnership John and Ryan have developed after working on so many projects together.

So you're working on a new record right now. Do you want to start off by talking about that?

JF: Ummm... I don't know. I feel kinda funny doing that. I feel funny talking about something until it's done. I don't wanna exhaust the ideas by turning them into verbosity or something. For me, making music — it's something you just do. I could say the standard things like, "Flea's playing bass and my friend Josh [Klinghoffer] is playing keyboards and drums and synthesizers and I'm playing guitar and singing." But we're still in the middle of it, so I don't wanna talk about mixing it when it's not even mixed yet. I guess I could say we're concentrating on the mix being in a constant state of change and having things come up and down — not being in one static place — with things moving around a lot. I've been into that kind of sound for a while now. I would've done it on Stadium [Arcadium], but some of the personalities and differences of opinion made it where I couldn't take it to the extremes I would have liked to. The kind of sounds I hear in my head are instruments getting louder and softer and changing in tone and sound, and having the music be sonically always in a state of change.

You obviously have a huge commitment to both analog and home recording. I mean, your entire house is basically a studio. What got you into this? Most musicians don't take things this far...

JF: I guess I started noticing how much better I liked recordings that people did on tape more than I did recordings that people were making when they started doing them on computer. I started asking questions and reading books and magazines and noticing that the whole approach to recording in the '60s and the early '70s was far superior to the approach now — both in terms of fast execution, producing results, being able to make a record quickly and being able to come out with a good sounding record — at least in rock music. Electronic music is the only thing that's flourished in the digital age. It seems like you don't have people making rock records that sound as good as Master of Reality or Led Zeppelin II or things like that — there's a warmth there and an atmosphere there that you just don't get. Ryan and I read something by Joe Boyd [Tape Op #60] where he was saying that a big part of the reason that recordings had so much atmosphere and vibe in the '60s, was that they'd have the people all playing in one room — they wouldn't be playing in isolation booths. With the microphones placed right, the bleed in between the instruments was what was creating the atmosphere and what our ears register as being the vibe. That's something that's lacking when everybody's recording everything separately. Ryan was telling me about some people doing recordings where they'll do the toms separate from the snare and hi-hat [laughing], and things go to crazy extremes. But generally people do a lot of close mic'ing and they don't want any bleed, you know? So we're trying to incorporate more distant mic'ing and things like that — trying to incorporate the space and the air into the recording. Any room, no matter if it has a lot of bounce in it, or if it's a small room, that space is still gonna translate into some kind of vibe, you know? So, we started paying more attention to how people were doing it in the '60s. The '60s were coming out of the period of time when engineers really had to learn how to do it one hundred percent with the mic and no bullshit. We had gotten into a lot of weird habits in the Chili Peppers, like using a lot of compression and isolation booths and not having enough atmosphere. On the solo records, we started contradicting everything that the engineers who Ryan and I had been around were doing, and...