How did you get started in audio engineering?

My audio journey started when I was living in San Francisco. I had a tiny apartment right down the street from a club called The Boarding House. Lots of artists played there that I really loved. I found that there was a back door that [I] could use to sneak into the club, until one evening I got stopped by the sound guy who was coming out as I was going in. He told me, "You can't be here. Go buy a ticket." But I couldn't afford it. Emmylou Harris was playing that night, and I really wanted to see her show, so I said, "Is there something I can do? Maybe I could wash dishes or clean up after the show?" He said, "Well look, my assistant just quit, and I need somebody to help me with the sound check tomorrow. If you come back, I'll let you in tonight." I saw the show, came back the next day, ran cables, plugged things in, and stood on the stage and said, "Testing, 1, 2, 3." Then I kept coming back. At the beginning I wasn't really that focused on learning audio. I kept showing up because I got to see all these shows for free, but the more I did it, the more I enjoyed it, the more I learned, the more I started figuring things out. I ended up spending a lot of time there doing the monitor mixing and sometimes doing the front of house. The sound guy was also a bass player, and he eventually got a gig to go on a tour. When the two of us went to the manager, who had seen me working there for months – for free, I might add – to suggest he should hire me to do the job, the manager just said, "I can't do that. She's a girl." I never went back.

Why would he not hire you as a woman? What was the scene and setting in which that was acceptable?

I think it was just outside the box at that time. This was mid-'70s. A woman in that role was not something that people could wrap their heads around. I don't think it was anything specific aimed at me personally. I just think it was not the prevailing understanding of who did that job. I mostly remember him completely nixing the idea. I don't know why exactly. I never asked. But it was clear to me that I was capable of doing that kind of work, and that if I wanted to keep doing it, I needed to look elsewhere.

Is that how you transitioned into the more studio setting and environment?

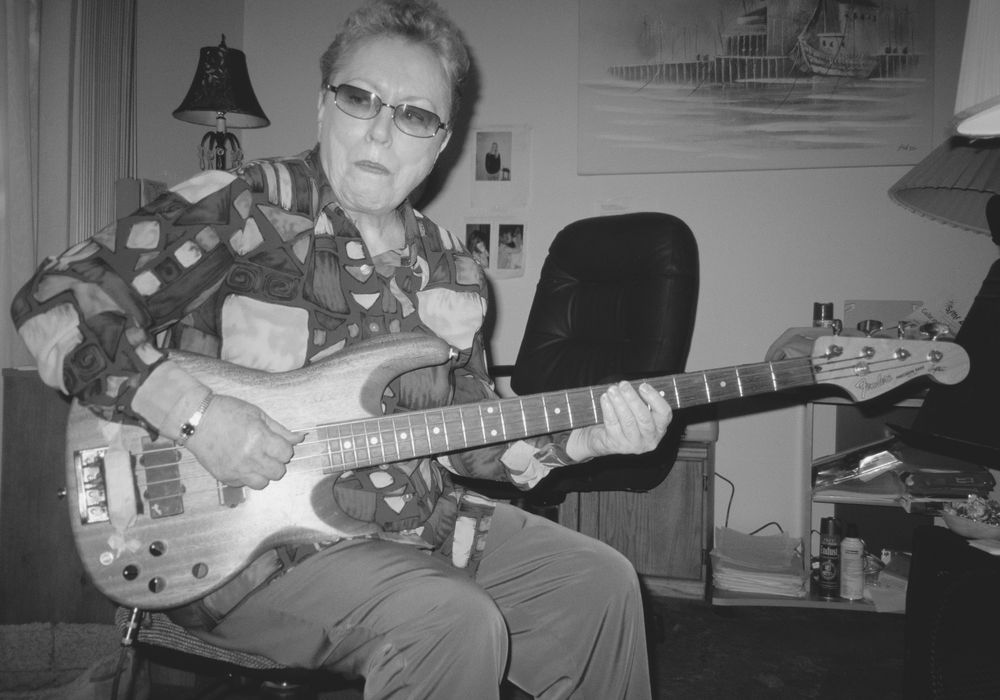

I have always known that I wanted a life immersed in music. The club was my first tiptoe into audio, but live sound really wasn't where my passion lay. I had always been someone who looked at album credits to see who the musicians were, who the producer was, and who the engineer was. I would listen to records and try to understand the production. "Why did the sounds sound the way they did? What were the harmony vocals doing? Why is there a drum fill? Where are the instruments in the stereo picture?" Ever since I was a teenager listening to albums, I was always curious about how they were made. The summer after The Boarding House experience, I took a Greyhound bus cross-country with a duffle bag and a guitar. I ended up in New York City and decided that I wanted to see if I could get a job in a recording studio. I'm a musician also, and I thought if I could get a job at a recording studio I could learn about the craft and also apply it to my own music. I drummed up a little resume and called a bunch of New York studios and got interviews. Most of the people I talked to were very happy to offer me a job as a receptionist, but the idea of a young woman being an assistant engineer just was, again, not something that was accepted at the time. Until, that is, I got to the Record Plant. They had a woman co-manager there who saw that I was serious. She said, "Okay, I'll give you a week." I showed up the next day, and I worked really hard. I did everything I was asked to do, and I did it as good as anybody could have done it. They hired me and I started getting paid! My goal was to not just meet some expectation, but I wanted to exceed it. By the way, I think that's really good advice for anybody in anything they do. If I could be an asset and blaze a bit of a trail along the way, so much the better. The way the hierarchy worked at many of the studios back then was your first job was as a runner, where you would do errands and clean the bathrooms and get people tea. All the lowly work. Then, you would work in the tape library, keeping track of all the tapes that were generated during the sessions. Then, when the assistant engineers would get free studio time late at night or on off hours, you could assist the assistants. Eventually, when you did that enough, and got a sense of how to work in a session, you'd get put on a session with a paying client. That was the apprenticeship ladder we climbed back then.

When you were at Record Plant, were people pretty open minded to working with women?

I'd say the staff was welcoming and very supportive, but often the clients were more resistant. I took a little bit of pleasure in watching peoples' minds change. They would see a girl come in, start to plug things in and push the buttons, and set up the mics – once they saw that the work was getting done and that there was a person in the room that was just as capable as one of the boys, it usually stopped being an issue. I was very lucky because producer Jack Douglas [Tape Op #90], who used the Record Plant for many of his records [Aerosmith, Cheap Trick, Patti Smith], started requesting me on his sessions. I became part of a team with Jack and Jay Messina [#90], who was one of the Record Plant's top engineers. I was the assistant on many of their projects. That was an important learning experience for me. I got to know what mics they might likely want on a certain instrument. I knew what compressors they might want to have plugged in on a certain channel. It became a point of pride that sometimes Jay would turn around and say, "Could you..." and then before he'd finish the sentence I'd say, "No, it's already done!" Many of the best producers and engineers at that time did projects at the Record Plant, and I was lucky that I got to work with several of the notable professionals who were making some of the seminal records at the time. I got to observe a lot of techniques, styles of mic choice and placement and sound shaping, track management, working with people, encouraging musicians, and creating an environment where people were creative and excited and into the work.

When I look at your roster of albums, there's such a common thread of this warmth and intimacy. Is that something that you take responsibility for? Was that the team, or was that the environment?

The recording environment was completely different for each one of them. It could possibly just be a coincidence, but it could also be the sense of community, or the sense of a shared vision of wanting to shape the music in a particular way so that it would connect with people. I'm very much a lyric person, so with a lot of the singer/songwriters I work with the songs and stories themselves tend to point me in the direction they seem to want to go, both in terms of arrangement and sound palette. There is an intimacy there, so that might be something that some of those records have in common.

What were some of your favorite sessions back at Record Plant?

One memory I have from the Record Plant happened when I was assisting on a Talking Heads record [Fear of Music] that Brian Eno was producing. They were doing a song called "I Zimbra," which was a poem that Brian had found that was all nonsense words. The poem was just the sound of the vowels and the consonants. It didn't really mean anything. Brian had those words written on a little scrap of paper. He and David [Byrne, Tape Op #79] were at the microphone singing, and they decided that they wanted a voice doing a higher octave. I'm a singer, but they didn't know that; When you're in the studio, you're there to serve the artist and not to promote yourself as a musician. In any case, I was a girl with a higher voice, so they asked, "Can you sing it?" I remember standing at the microphone with Brian on one side and David on the other, holding this little scrap of paper, and us singing this crazy song. It took a few times through to get it right, because there weren't any recognizable words, but it was really fun, and that's what ended up on the record.

Did you ever get to the point where you were not impressed by the caliber of folks you were working with?

Not really, although sometimes I'd have an idea about an artist based on their work, and when I'd meet them in person and work with them, I'd realize that everybody, no matter how talented they are, is a flawed human being. Some people came down a little bit off their pedestals. I will tell you one person who did not was Joni Mitchell, who I had the great good fortune to do three records with. I was constantly impressed by her.

What happened after [working at] Record Plant?

I left the Record Plant and then I worked at Atlantic Studios for a while. I was feeling that I had reached a glass ceiling at the Record Plant. When the manager from the Record Plant moved to Atlantic, he invited me to come work there. I was still a second engineer but occasionally did odds and ends of engineering. Then I got offered a job at a small, one-room studio on the east side of Manhattan called Celestial Sound. They offered to hire me as an engineer, and even though it wasn't a big, fancy, famous studio, they assured me that I was going to get a chance to be in the driver's seat, so I wanted to take advantage of that. One of the first projects I got to engineer there was a Brian Eno album called On Land. Then I worked with David Byrne, recording music he had written for choreographer Twyla Tharp's dance ballet The Catherine Wheel.

Is there anything that stands out about recording On Land?

One interesting thing about that record is that Brian had done a bunch of outdoor recordings with a field recorder. We transferred those recordings to 2-track tape, and then we slowed everything way down. I think we recorded it at 30 ips [inches per second] and we might have slowed it down to 7.5 ips. The source sounds became unrecognizable. When you hear crickets and frogs at their normal pitch, there are notes and harmonics within the sound that we don't really notice. When you slow everything way down, it becomes this drone that sounds musical. We did that with a lot of the elements that he had recorded out in the field. The slowed down version got transferred to 24-track tape, and then he would build on top of that. He added percussion and voices and had various musicians come in and add more layers. That's what became On Land.

Speaking of analog and tape, is there anything that you miss about recording in analog that you can never recapture recording digitally?

Analog can be very cumbersome compared to digital, but it was where I started so I went into digital kicking and screaming. Not so much because of the sound, but more because I didn't want to be locked into looking at a screen. I wanted to be able to look through the glass and connect with the musicians, to have that eye contact, feedback, and communication. I didn't like the fact that that screen got in the way. Now I'm comfortable paying attention to all of it. I do remember that, for a while, working on digital platforms had felt like riding a horse, where the horse is totally in control and you're just holding on to the keyboard and the mouse for dear life. I remember a day when I felt like, "Okay, I've got this." From that point on, I was better able to integrate the technical with the emotional and musical elements. I do think the analog vs. digital conversation is way less important than using the tools you have, whatever they are, with care and intention.

I am obviously intrigued by Double Fantasy with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Is there anything you want to share about that session?

It was absolutely a highlight for me to be able to work with them. He hadn't been in the studio for about five years while he was raising their son, Sean. When John came back to the studio, he was so excited. Like a little kid in a candy shop. That energy lit up the room every time we were there. Everyone involved was carefully hand-picked. The reason I was allowed to be a part of it was because I had been working with the producer, Jack Douglas, and he thought that Yoko might enjoy having another woman on the scene. She didn't seem to be that interested in it one way or the other, but anyway, I was honored to have been a part of that project. It's a great, great memory.

Does anything fun stand out about Rickie Lee Jones' Traffic from Paradise?

I was assisting with Joni Mitchell at her home studio, and I got a call from Ocean Way Studios, where I had been on staff after moving to L.A. One of their assistants was sick, and even though I didn't work there anymore, they asked me if I would come and fill in. I got a day off from Joni's record, and I went to help out at Ocean Way. I worked that day with Rickie Lee and the engineer. Then that night I got a call from the engineer, and he said, "The flu that the other assistant had, I got it. Now I'm sick too. You obviously know what you're doing, so can you take over the session tomorrow?" I said, "Of course." I knew where everything was. I'd done the setup and met Rickie and worked for the day. It was not a problem. It was like the stand-in for a Broadway show getting their big moment. That's how it felt. I showed up, and the studio, being short staffed, put some new kid who had never been on a session before in as my assistant. I got through the day. It was totally fine. Then the next day, I showed up and Rickie said, "I called the engineer, and I told him not to come back. You are the engineer now." So, that's how I got to do Traffic From Paradise. By the way, Joni was gracious about it, and I was able to continue working with her in between Rickie Lee sessions. It was as if the universe kept dropping breadcrumbs in front of me. I kept following them. I imagine those breadcrumbs were all there because it was something that I cared about a lot, and I trusted the adventure.

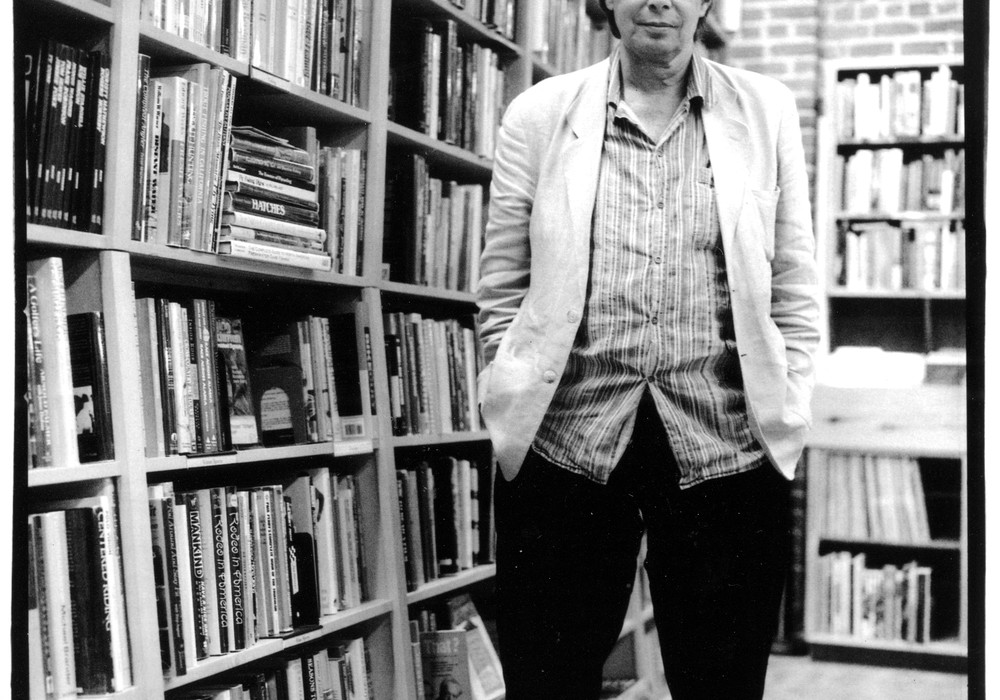

Tell me about your studio now. When you left Los Angeles and moved up to Woodstock, you created your own space. Did you design it yourself or build it up over time?

I designed it myself. It's the ground floor of my country cottage; I live upstairs and the studio's downstairs. Easy commute! It's adjacent to state [owned] land, so there are beautiful woods and forests all around. It's on a quiet, country road, so I can record with the windows open most of the time. It's a warm, creative environment. People come and they feel comfortable and supported. If we want to take a break, we can take a walk in the woods. It's a good palate cleanser to be able to focus on the work and then step outside. The studio is not big, but I have recorded bands there. My preferred way to work is to do one overdub at a time. It's not hard and fast, but because of the way the space is set up that tends to be the case more often than not. I enjoy that, both as an engineer, because I have much more control over exactly how things sound, but also as a producer, because I can concentrate on all the details of the performance. When it's just one person [playing or singing], I can be listening on such a more careful level to every aspect.

Do you see any resistance from the musicians who are used to playing in a group band atmosphere?

No, I think most musicians are pretty accustomed to doing both. Woodstock is a fabulous community. There are many incredibly talented musicians here, and the pool of musical resources is such a gift. I can hire from this repertoire of amazing players, like casting a movie, picking and choosing the people who will resonate with whatever's going on with the project I'm working on. One thing I've learned is that it's not just about players playing the notes. Lots of people can play the notes. I find that the best musicians are the ones who are not only playing the notes, but [are] also playing the sound. The touch, the articulation, the dynamics, the way a phrase is expressed, and what makes the instrument speak. This is not just for instrumentalists, but also for singers. As an engineer, before I reach for EQ, I can listen to how the hardness of the pick changes the guitar sound, what kind of beater is on the kick drum, how hard the drummer is hitting the snare, which pickup the electric guitar player is on, or where the singer is taking a breath. Those things change the sound and can also inform the performance. Working one-on-one with people in that way is so nice because we can concentrate on those details and make the parts shine.

Are you good about tearing yourself away from long sessions?

I like to take breaks, both for my ears and for my head. I do find that it often works well to get a variety of good performances, and then spend time later picking and choosing the best of what happened and putting that together, and maybe moving parts around. I do find myself spending a good amount of time alone, piecing together the puzzle.

How are you listening back?

I have a pair of Genelec 1031As that I love and have always worked with, so I know them well. When it comes down to the final stage of mixes before mastering, I'll check them on other systems and see what needs to be adjusted. Because of digital now, we're mixing as we go all the time. Levels, EQ, reverbs, and effects come back the way I left them and then get tweaked along the way. It's so much easier than the days when we would finish all the recording, then switch gears for the mixing stage. We'd make a million little marks on the faders and take Polaroids of the settings on the board and the outboard. If you needed to make a change a week later, it would never come back exactly the same. It's not like that anymore, thank god.

What do you think the future holds for you?

I want to keep making music and empowering other people to make music. I enjoy when somebody comes in with a vision and tasks me with helping them fulfill it. It's not just about meeting an expectation but trying to exceed it, so that when their project is done, they feel that it's better than they imagined. That's my goal. I don't always get to that, but I want people to not only be happy with the way that their gift is presented, I [also] want them to feel that they grew along the way, that they learned something, and that it will be even better next time. That's always exciting to me, and I want to keep doing that. Also, I'm a singer and a songwriter myself, so I want to keep making space for that in my life, as well.

In Tape Op #150, Bella Blasko credited you with her start in audio, your encouragement and sharing of knowledge. Is that something you do a lot of?

I'm happy to help anybody who is interested in learning. I met Bella because I was teaching recording at Bennington College, and she was one of my students. She reminded me a bit of how I was at the beginning. I saw this real eagerness, passion, and facility. I was so happy to be able to help light that fire and keep adding more fuel. I got her an internship at a big studio around here. After that, she was on her way. She brings so much musical sensitivity to her work. It's important for anybody who's engineering to be able to not just be a button pusher, to not just throw 300 plug-ins on every track, but to approach the work with a musical sensitivity as well as a sonic one. One of the reasons I was happy to be teaching courses on recording was that I was hoping to encourage more young women to join in. I had many wonderful guys in my classes, but I wanted to especially make sure that there were girls who could see a path into this world. It's a surprise to me that there are still relatively few women doing this work. Why aren't there more? I don't have the answer to it, but I know that many of the roadblocks I encountered have dissolved since I first started out. I want as many voices and visions to be recognized and supported as possible. Women have a lot to offer, not just in terms of their place in the music business, but in terms of the way that we can bring a beauty into the world that can be unique. I want to support that. In the studio, I want to empower beauty and creativity and meaning as much as possible – on both sides of the glass.